Is New York’s most ubiquitous Jew leaving New York behind?

For the past half-century, Larry ‘Ratso’ Sloman has been everywhere in the city — now in his 70s, he may have had enough

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

It seems as though Larry “Ratso” Sloman has been everywhere in the last half-century: He toured with Bob Dylan, hung out with the New York Rangers, edited National Lampoon magazine, ghostwrote the memoirs of major celebrities, and recorded his “decades-in-the-making” debut album, which was released when he was 70.

Sloman is about to turn 75 and the lifelong New Yorker — and proud Jew— still has a lengthy to do list: finishing a biopic script for a major Hollywood studio, developing two TV projects with his pal Kinky Friedman, producing a documentary on “the new antisemitism” and writing his own memoir about life as the Zelig of popular culture.

“Ratso and Larry Sloman are not the same thing,” observed longtime friend Mark Jacobson. “Ratso is this spectacular character that Larry Sloman invented and he plays him to the hilt. He doesn’t just appear in the background of the picture. Somehow, he’s part of the show.”

“He’s a hybrid artist-journalist,” said the music biz macher Danny Goldberg. “He’s got the spirit of an artist but the work tenacity of a journalist. He’s also a fan. When Ratso falls in love with an artist, he’s all in.”

How Ratso became Ratso

Calling Sloman a fan of Bob Dylan would be an understatement. He first met Dylan sitting in a parked car in Manhattan and convinced the singer to let him write a preview of the forthcoming Blood on the Tracks album. Dylan agreed and then invited him to join the Rolling Thunder Revue tour. Sloman was on hand for many of the 57 performances during 1975 and 1976. The caravan of traveling troubadours included Joni Mitchell and Joan Baez. It was Baez who told Sloman he reminded her of Ratso Rizzo, the con man character played by Dustin Hoffman in Midnight Cowboy.

Sloman quickly embraced his new nickname and his gig covering the Rolling Thunder Revue for Rolling Stone. Once that assignment was over, Dylan allowed him to stay on and chronicle the tour, which he did in his first book, On the Road With Bob Dylan. It is said to be Dylan’s favorite Dylan tome.

Before he was Ratso

Sloman was a middle-class commuter student at Queens College, who made his way into the East Village, where the counterculture was thriving in the mid and late 1960s. He initially was a gopher at the East Village Other, the underground newspaper.

In 1967, he met Abbie Hoffman and tagged along on the anarchist’s famous New York Stock Exchange stunt, watching as Hoffman rained 400 dollar bills down on the floor from the visitor’s gallery, causing a frenzied scramble for the cash. He wrote about the experience in Steal This Dream, Sloman’s oral history of the Yippie showman who referred to himself as a Jewish Road Warrior.

“Abbie was one of my first Jewish role models,” said Sloman, who now occupies the SoHo apartment that another Jewish Yippie, Jerry Rubin, had shared with the troubled folksinger Phil Ochs.

Professional writer, professional schnorrer

Sloman’s career as a professional journalist began in 1970 with a story written on spec for Rolling Stone about a rock riot in Milwaukee. An incensed crowd tore up a lakefront park that summer after Sly and the Family Stone showed up late and played a drug-addled two-song set before leaving. At the time Sloman was a volunteer in VISTA, the domestic version of the Peace Corps, working as a paraprofessional in an inner-city school and helping a radical priest after hours to organize welfare mothers.

After escaping the draft during the Vietnam War because of his eyesight, Sloman went to grad school to study sociology at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. He became music editor of the student newspaper, The Daily Cardinal, and wasted no time introducing himself to the major record labels. A deluge of free LPs then commenced. Years later as editor of High Times magazine, Sloman availed himself of one of the job’s perks: free books at a bookstore owned by the magazine a block downtown from his SoHo apartment.

Jacobson, also a son of Queens and an accomplished writer, noted Sloman’s love of the freebee. The two writers co-hosted a live internet radio show at The KGB Bar in the East Village for five years, a gig that came with no pay other than an open bar for the show’s hosts.

As far as the KGB’s owner was concerned, “Ratso schnorred over the schnorring line,” Jacobson said.

“Ratso has never paid a check my entire life. And we’ve been friends forever. I met him on the gangplank of Noah’s Ark,” Richard “Kinky” Friedman told me.

Friedman is known for both his country music band called The Texas Jewboys and a series of mystery novels starring an amateur detective named Kinky Friedman and his Watson, Ratso Sloman. Friedman told me that he and Sloman are developing two TV projects.

“I think our best days are on the way,” said Friedman, who runs a summer camp on his ranch in Texas for children who lost family members as a result of military service. When I suggested that running that sort of camp might be considered a form of tikkun olam, repairing the world, Friedman told me he had no idea what the term meant.

For his part, Sloman seemed not to know the term tashlich, the ritual Jews perform during Rosh Hashanah, when they symbolically transfer their sins to bread and toss it into a body of water. But he is familiar with the practice, both because he’s done it before and because he directed the 1984 video of the Bob Dylan song “Jokerman,” which begins with the line “Standing on the waters/ casting your bread.”

Sloman says he fasts on Yom Kippur and used to go to shul before the pandemic, dropping in on small Lower East Side synagogues, the kind of places that were “just happy to have any Jews come in.” More recently, he’s been reluctant to attend public events, so his Yom Kippur ritual has consisted of fasting and listening to a recording of Kol Nidre by the 1940s cantor and opera singer Richard Tucker.

Stern experience

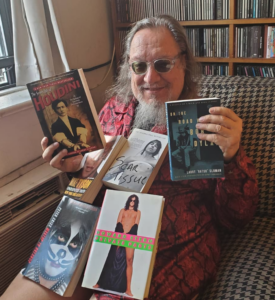

Sloman’s apartment has a huge collection of books about Bob Dylan, Adolph Hitler and Jesus Christ. There’s a bit of shelf space taken up by books written by Larry Sloman or the result of his collaboration with some big stars, including Howard Stern.

Credited as an editor of Stern’s two books, Private Parts and Miss America, the job involved riding in a limousine with the radio star to his home on the North Shore of Long Island, waiting for Stern to finish his 20-minute transcendental meditation routine, then jumping into the interview during the remainder of the ride. Stern had Sloman on his radio show many times, sometimes calling the writer at home and waking him. Sloman soon found that the name Ratso could open doors.

When he went in to buy a new computer at a P.C. Richards’ electronics store, he was told it wasn’t in stock until he mentioned that his name was “Ratso” Sloman.

“Not Ratso from the Howard Stern show?” he was asked.

Yes, that Ratso. The computer was promptly transported to the store from another location while Sloman waited.

On another occasion Sloman arrived backstage at a Bob Dylan concert in Jones Beach and found that the catered spread had been cleared. He struck up a conversation with the chef, who asked his name.

“You’re not Ratso from the Howard Stern show?” the chef inquired.

He was indeed. And the chef proceeded to cook the hungry writer a meal.

Howard Stern is “a real mensch,” Sloman said. “One of the most decent people I know.”

After he’d worked on the Stern books and they became bestsellers, he helped magician David Blaine, Red Hot Chili Peppers’ lead singer Anthony Kiedis and boxer Mike Tyson with their books. Sloman also co-wrote a biography of Harry Houdini.

Welcome back, Larry

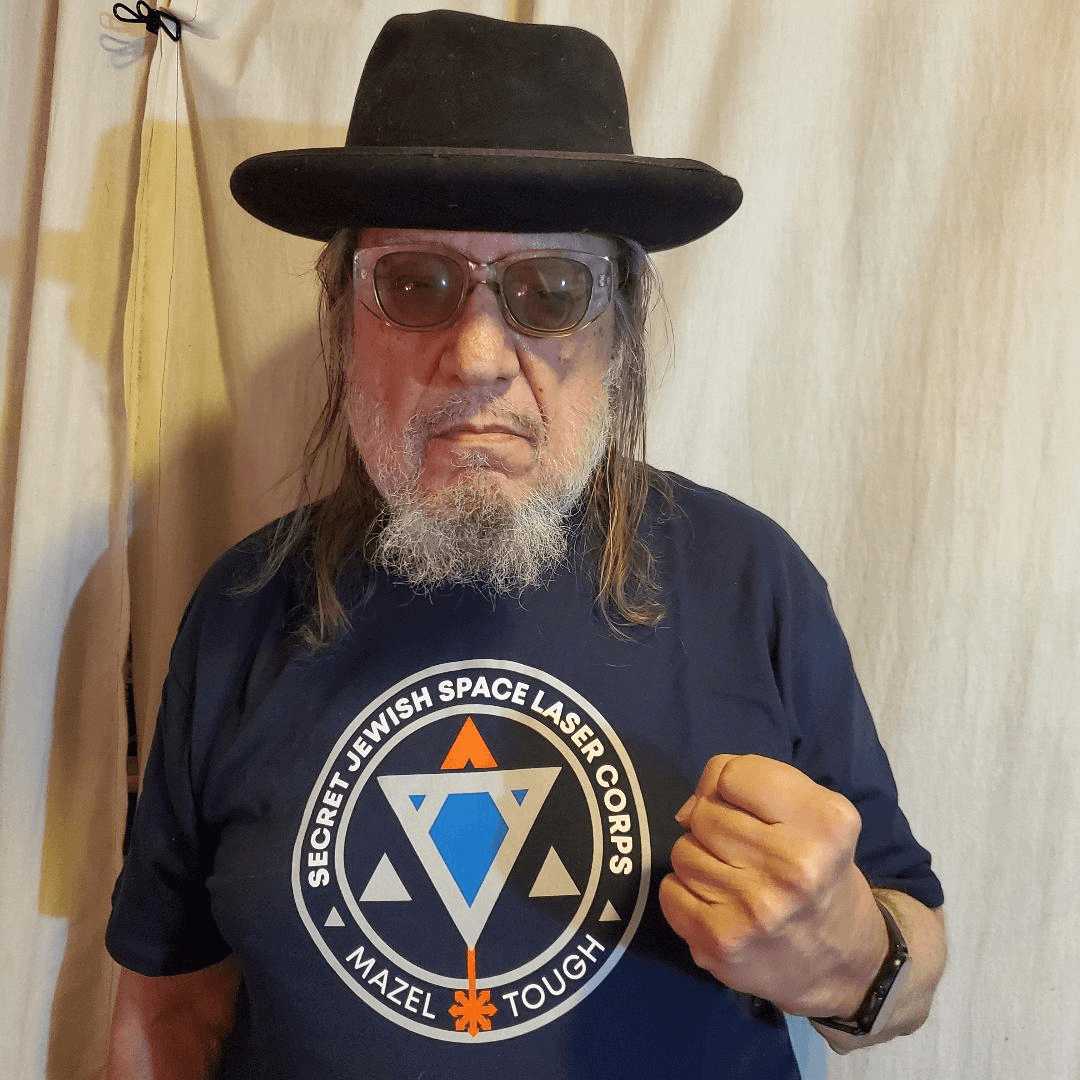

Sloman has an unmistakable punim. When he grew out his beard during the pandemic, he could have easily passed for an old Hasid on the streets of Crown Heights or Borough Park.

That face has graced the silver screen many times in recent years. Young Ratso is seen frequently in Martin Scorsese’s documentary on the Rolling Thunder Revue tour. In the Leonard Cohen doc Hallelujah, Sloman gets nearly as much screen time as Cohen. He also has a cameo in the 2019 feature film Uncut Gems. He hurriedly walks by Adam Sandler’s character Howard Ratner and wishes the Jewish jeweler “a good Pesach, Howard.”

“All right, Larry. You’re a Jew again. Welcome back,” the jeweler responds.

Though he’s never been officially credited with it, Sloman insists he’s the source of the catchphrase “Yeah, baby!” in the Austin Powers films. According to Sloman, Mike Meyers appropriated the exultation after playing ice hockey with Sloman at an indoor rink on Manhattan’s far west side in the 1990s. Sloman said he would let loose with a “Yeah, baby!” after someone on his team scored a goal. (Sloman hung up his skates after he had his hip replaced.)

What’s next for Ratso?

Besides literature and motion pictures, what other realms are left for Ratso Sloman to conquer? Why, recorded music, of course.

Sloman said he started writing songs when he came off the Rolling Thunder tour. He co-wrote lyrics for songs with his friend John Cale, one of the founders of the Velvet Underground.

His debut album Stubborn Heart has cameos from Sharon Robinson, Leonard Cohen’s co-writer and backup singer, as well as Nick Cave.

“That record meant a lot to him,” said Jacobson, who chuckled recalling Sloman’s insistence on playing him cuts of the album while it was a work in progress.

The album was definitely not an embarrassing vanity project. Critics were keen on the album but some close friends said Sloman’s singing on the recording might be summed up as “Ratso imitating Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan.”

“They were my mentors,” Sloman acknowledged.

He says he does have plans to record a second album, which he promises will include “some new guest artists” and a song titled “The Combat Zone,” whose title is taken from the name of Boston’s adult entertainment district. During his time with the Rolling Thunder road show, Sloman was sent there to scout locations and extras for Renaldo and Clara, the widely panned four-hour Dylan film shot during the tour.

In the meantime, though, Sloman will continue to be Ratso, tooling around town in his Honda CR-V with the RATSO license plate. He tends to stand out — his baseball caps are emblazoned with the Hebrew word chai or the phrase Oy Vey, and he’s fond of wearing a T-shirt with two pine trees and the words Yo Semite below them as well as a couple of bekishes, the black silk frock coats worn by Hasidim.

Sloman says he went to shops in Satmar Williamsburg to buy the coats, in one case explaining that the garment was needed for a production of Fiddler on the Roof. He told me he wants the record to note that he was wearing bekishes way before the fashion designer John Galliano started doing it.

Last days in New York

Sloman subscribes to the theory that there is a long line of Jews whose mission is to stir things up. That list runs from Jesus Christ and continues on through Sigmund Freud, Lenny Bruce, Abbie Hoffman and Kinky Friedman. He sees himself as part of that tradition of Jewish troublemakers, though his take on Jesus isn’t exactly in sync with mainstream Jewish theology.

“To me it’s tragic that most Jews don’t see Jesus as an immensely profound Jewish prophet,” he explained. “I think Bob [Dylan] sees him that way and I know that Leonard [Cohen] did. He told me so … In retroactively turning on Jesus, the Jewish community misses out on his teachings like the Sermon on the Mount, which is probably one of the most beautiful and Jewish declarations of social justice.”

Whatever you may make of Sloman’s religious observance, there’s no confusion about his defense of Israel. He considers himself a hardliner on the issue. He made his one and only trip to the Holy Land in November 2017. He spent a total of five days in the country and made a point of visiting the Wailing Wall. The trip was made to express moral support for his friend Nick Cave, who refused to honor the call to boycott the Jewish state and played two concerts in Tel Aviv. Sloman attended both performances, joined by the late music producer Hal Willner.

“I always wanted to go,” said Sloman. “I had a much greater appreciation for what the regular citizens in Israel go through. It made me much more supportive of Israel.”

Sloman is not about to make Aliyah, but he is wondering whether he can hack living in New York City at this point. Sounding like a cranky geezer, he grumbles about restaurant sheds taking up the sidewalks and streets.

But two recent personal experiences have shaken the man. He was stunned to see someone shooting up on the stoop of his SoHo apartment building in broad daylight. And his wife came close to getting mugged on her way to Washington Square Park to walk the dog.

“The quality of life in the city is shot,” he groused.

Sloman made a temporary escape to a beach community on Long Island, staying with a friend while he worked on a screenplay but is currently on strike with the Writers Guild of America against Hollywood.

“It’s so much nicer not to have to deal with the filth and the hectic life in the city,” he said.

Mark Jacobson is not surprised to hear that Ratso Sloman is talking about getting out.

“He’s an alte kaker,” Jacobson said. “He’d move to Florida if it didn’t cost him so much money.”