FIRST PERSONA bar mitzvah boy, a Little League team and a boxer looking for redemption

Emile Griffith, a boxer with a tragic story, sponsored my Little League team. Would he let me skip practice to study for my bar mitzvah?

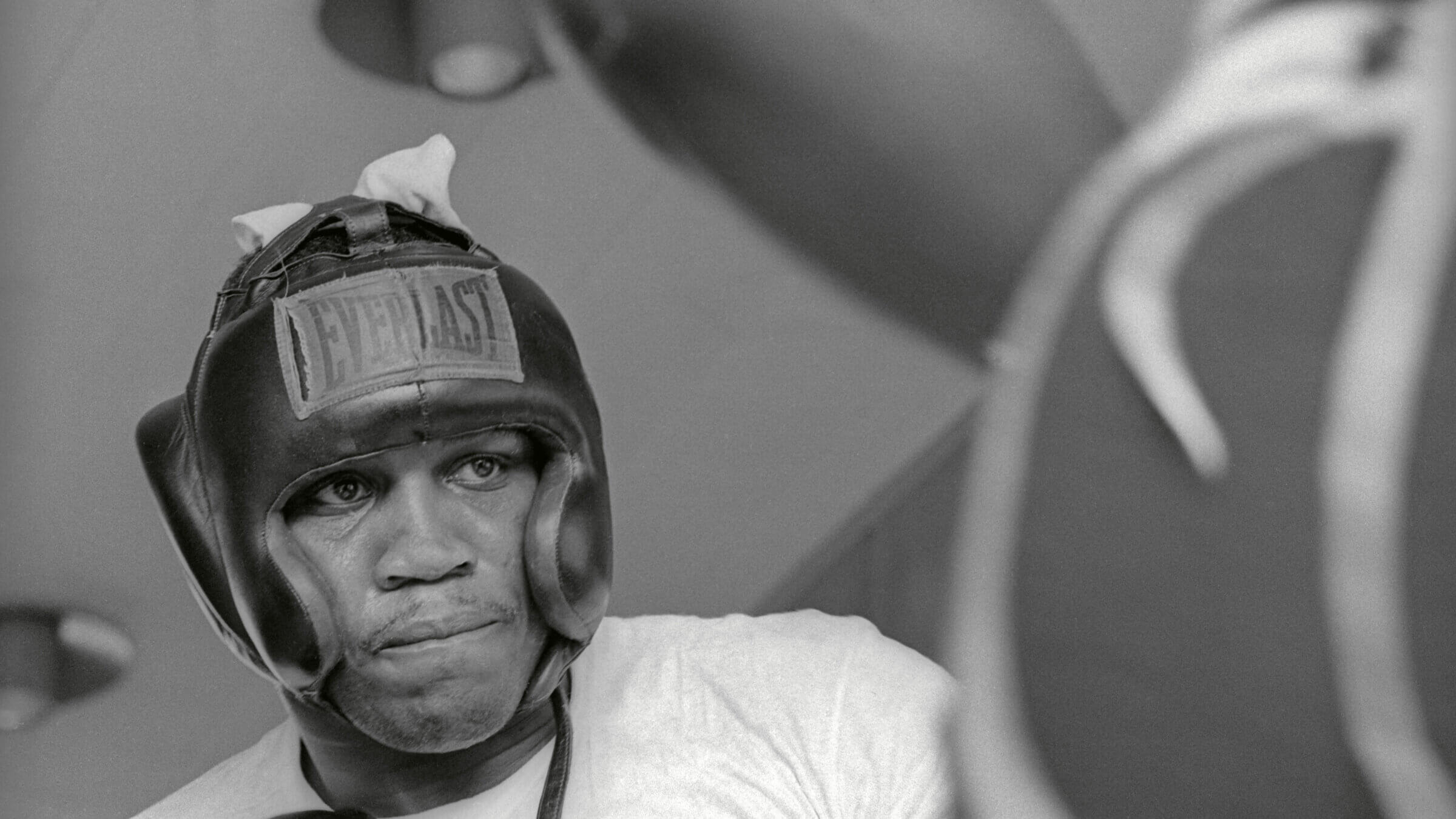

Boxer Emile Griffith in training in 1968 in New York. Photo by Santi Visalli/Getty Images

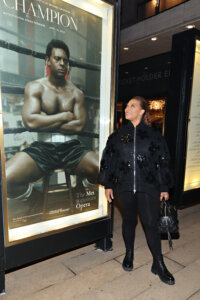

Champion, the new opera about boxer Emile Griffith that closes this weekend at the Metropolitan Opera, brings back memories. My connection to the champ himself began when I was 12 in 1964. I was looking for permission to ditch baseball practice so I could study for my bar mitzvah; Griffith was looking to atone for a tragic boxing match that had resulted in the death of his opponent.

Griffith trained in a run-down gym near Chelsea Park on 28th Street and 10th Avenue in Manhattan. Born and raised in Chelsea, I played baseball in the local Little League in Chelsea Park. A bar and grill, hardware store, and other neighborhood shops sponsored teams to defray costs of uniforms and equipment. Griffith, at the height of his fame, sponsored my team, which he personally named “The Emile Griffith Griffs,” emblazoned in gold on our shirts.

I recall him coming to our Saturday morning games to cheer us on and to give advice. Tall, muscular and handsome, Griffith wore a solid gold bracelet with the word “Champion” on it, proclaiming he was welterweight champion of the world. Grammy Award-winning composer Terence Blanchard and Pulitzer Prize-winning librettist Michael Cristofer could not have chosen a more apt title for their opera.

The worst team in the league

Despite our illustrious sponsor, the Griffs were the worst team in the league. Our manager scheduled extra practices after school, which one afternoon was at the same time as my bar mitzvah lesson. I asked my manager for permission to skip it. He couldn’t decide and sent me to Griffith. That brought me, a 12-year-old boy on the eve of his bar mitzvah, to the edge of a boxing ring to talk to the great Emile Griffith.

I remember going up the dark staircase to the second-floor gym, which reeked of sweat. A bare lightbulb above the ring supplemented the meager sunlight coming through the soot-covered windows. There in the ring was the champion himself, sweat gleaming on a physique that resembled the Colossus of Rhodes. He was sparring with someone, and the noises of strenuous effort permeated the room. No one noticed me; I finally told someone on his staff that I was a member of the Griffs, and that I needed to talk to Griffith.

During a break, Griffith saw me, stepped down from the ring, and asked what I was doing there. I explained that I wanted his permission to skip practice because I had to study for my bar mitzvah. Griffith, who always knew what to do in the ring, seemed unable to decide this momentous request.

I showed him a soft-covered booklet with Hebrew words written in it that I used to study. He took it in his hands, carefully turning each page to the end, and then started over again at the beginning, staring at the letters for several minutes. Clearly, he had never seen Hebrew before and he did not know the significance of a bar mitzvah. But I could see that he was curious and trying to understand what it was all about. I tried as best as I could to explain that it was a very important event for me and my family, and that I would have to chant the Hebrew words of my Haftorah out loud in front of my entire synagogue on a Saturday morning to celebrate turning 13.

He seemed to realize that my Hebrew lesson was more important than Little League. He excused me from practice, wishing me well in my lessons and saying that he would see me at the next game.

What Griffith did not know as he stared at my booklet in that dilapidated gym was that it contained the words of the prophet Isaiah: “I wipe away your sins like a cloud, your transgressions like mist. Come back to Me, for I redeem you.” It now seems to me as if these words were addressed directly to Emile Griffith.

In the mid-1960s, Griffith was one of boxing’s best-known personalities. An immigrant from the Virgin Islands with little formal education, he was working in a Manhattan hat factory when his boss, a former amateur boxer, took him to a trainer. A year later, he was a Golden Gloves champion, and in 1963 and ’64, he was voted “Fighter of the Year” by the Boxing Writers Association of America.

At the weigh-in for the fateful fight in 1962, Griffith’s opponent, Benny “the Kid” Paret, taunted him in Spanish with an anti-gay slur, maricón. It was a well-known secret in the boxing world that Griffith was gay and that he frequented underground gay clubs. (The Stonewall rebellion and the birth of the gay rights movement were still a few years away.)

Enraged by the insult, Griffith seemed ready to take Paret on then and there, but he saved his fury for the match. That night, Griffith pummeled Paret with unusual force; the referee didn’t stop the fight until it was too late. Paret was taken to the hospital unconscious and died 10 days later. The incident led New York’s Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller to form a commission to study boxing safety; Griffith and the referee were both exonerated.

A poignant scene in the 2005 documentary, Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story, shows the boxer asking Paret’s adult son for forgiveness. By then, Griffith was living in poverty in a small Long Island apartment, riding the bus to his job as a security guard. Gone was the physique that made him the envy of the world. Gone was the solid gold bracelet with “Champion” on it.

Also long gone were the Emile Griffith Griffs. We lost every game that season, and I never got a single hit at bat. But I’m glad I played for the Griffs because it brought me into the orbit of this extraordinary person. The Hebrew words that Griffith stared at, standing with me in that gym, state that forgiveness of sin comes through true repentance. Griffith couldn’t read that text, but he, like the Prophet Isaiah, knew and understood the meaning and importance of repentance better than anyone.