In Berlin, the Nazis burned Freud and Fitzgerald. Now Florida’s banning Eric Carle and Margaret Atwood

I went to Berlin to commemorate the 1933 book burnings. But all I could think about was the books banned at home today

A flyer for a ceremony commemorating 90 years since the Nazis burned books in Berlin. Photo by Tom Freudenheim

BERLIN — So there I was in Bebelplatz, next to the Berlin opera house, across the city’s grandest boulevard from a great university, at the site of the most notorious Nazi book burnings exactly 90 years ago.

The memorial to this dastardly event is almost hidden in the center of a vast plaza: a rectangular sheet of glass interrupting the stones. You might walk right over it on your way to one or another tourist destination. But there was an event on Wednesday to commemorate the anniversary, so people were checking it out, including a group of Israelis with a Hebrew-speaking guide.

Through the musty rectangle of glass you can see empty shelves, meant to evoke the loss of those thousands of books deemed “un-German” that were gleefully and ceremoniously burned right here and in more than 30 other university cities.

They burned Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Tolstoy

The burned books of 1933 included works by Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky, Joseph Conrad, D.H. Lawrence, and H. G. Wells, and of course the Germans Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Thomas Mann and Alfred Döblin. Döblin, a novelist, essayist and doctor, was my father’s first cousin.

I’ve often visited Bebelplatz, alone and with visitors, always pointing out the quiet eloquence of the “Empty Library” memorial created by Israeli artist Micha Ullman. But this year when I looked down through that glass, I saw the empty library shelves in Florida schools.

More than 200 titles were banned in various school districts across Florida over the last two years. Not Einstein and Freud — at least not yet. But a variegated list that includes Toni Morrison, Khaled Hosseini, James Baldwin, Eric Carle, Jonathan Safran Foer, Kurt Vonnegut, Margaret Atwood, Arundhati Roy, Isabel Allende and Martin Luther King Jr.

If there’s any point to these anniversary commemorations, it must be to remind us that the past is not past. Four days before the 1933 Bebelplatz book burnings, the Nazis raided the Institute of Sexual Research founded by Magnus Hirschfeld, an early leader in the gay rights movement. I assume there were no 90th–year commemorations of this raid in “Don’t Say Gay” Florida last week.

A surprise guest

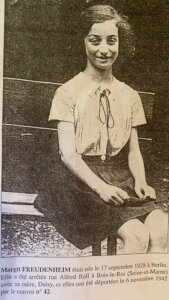

A surprise guest of honor on Wednesday was Beate Klarsfeld, the 84-year-old French-German journalist and Nazi hunter, who handed out pamphlets with poignant photos of children captioned (in German): “1933, the Nazis burn books! 1943, the Nazis burn the children of the People of the Book!”

One of those children was my sister, Margit. Klarsfeld’s 1983 book documenting the deportation of Jews in France included Margit’s photo, the site of her arrest (Bois-le-Roi), and the date of her deportation from Drancy to Auschwitz (Nov. 6, 1942, on Convoy No. 42).

I had come to the ceremony out of curiosity but suddenly was filled with emotion. I pulled up on my phone the image of Margit’s page in Klarsfeld’s book, and went to show it to Klarsfeld’s husband and collaborator, Serge, who was seated in the front row. He examined it carefully, reading the text below Margit’s photo, looked me in the face and sighed.

After a brief introduction about book banning in other countries, especially in Pinochet’s Chile, the program had prominent literary and arts figures reading the works of writers whose books were burned, including Erich Mühsam, and Kurt Tucholsky, and mostly Bertholt Brecht. The annual event is sponsored by the leftists in Germany’s Parliament, and I found myself wondering how the Congressional Progressive Caucus might handle such a thing back home.

The pitfalls of law

It was a beautiful, sunny afternoon, and my eye wandered to the Staatsoper — the opera house — which I first visited in the mid-1960s with a cousin who lived in East Berlin. Then my gaze rested on an elegant (old? rebuilt?) building in front of me with the name “M.M. Warburg” carved in large letters carved near the top, reminding me of my first job, in 1961 at New York’s Jewish Museum — housed in the Warburg mansion, at that time still mostly preserved as it was when the family lived there.

To my right, the law faculty of the Humboldt University served as a potent reminder of the pitfalls of the law: Burning books was legal in Germany in 1933.

On Thursday, I would see Tannhäuser at the opera house, which I still think of as Daniel Barenboim’s, though he recently resigned as director. Barenboim is the man who in 2001 defied Israel’s ban on public playing of Richard Wagner’s music, prompting perhaps equal amounts of ovations and outrage, including a call for orchestras in Israel to ban Barenboim.

I think bans are bad, generally. And as I sat at the Bebelplatz ceremony, I realized that instead of my Jewish self being uncomfortable because of what happened here 90 years ago, my American self is making me squirm about what is going on at home right now.

When the program ended, after recitations and denunciations of Nazi Germany and Pinochet’s Chile and current attempts to annihilate Ukrainian culture, I was incredibly relieved that no one had mentioned censorship in Florida.

Correction: Due to an editing error, this story incorrectly stated that the author worked for a Berlin museum. It has been updated to refer to the Jewish Museum in New York.