No, Steely Dan hasn’t aged all that well, but then again, neither have we

‘Quantum Criminals’ reveals the jaundiced and Jewish-inflected cynicism behind the slick musicianship of Steely Dan

Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen performs in 2006. Photo by Getty Images

Quantum Criminals: Ramblers, Wild Gamblers, and Other Sole Survivors from the Songs of Steely Dan

By Alex Pappademas & Joan LeMay

University of Texas Press, 260 pages, $35

During my junior year of college, there was a freshman in my dorm named Steve, whose older sister had been a friend of mine in high school. Steve was a good kid, but I occasionally felt compelled to step in like a big brother and set him straight — like the time I saw him sitting in the lobby with a copy of A Decade of Steely Dan.

“What the hell are you doing with that?” I asked, upperclassman disdain seeping from my every pore.

Steve shrugged. “Steely Dan is awesome.”

“Oh yeah, right,” I snorted.

This would have been around 1988, at the height of my love affair with what was then becoming known as “alternative rock” — college radio-oriented music that seemed edgier, quirkier and far more intrinsically human than the vacuous, digitally-sculpted pop polluting the airwaves at the time.

Steely Dan, with their legendarily perfectionist approach to recording and what appeared to be their celebrations of proto-Yuppie decadence (“The Cuervo Gold/The fine Colombian …”) were, to my mind, harbingers of the shallow slickness and messages of conspicuous consumption that ailed mainstream music in the Reagan Era, and therefore THE ENEMY.

I forget the rest of our conversation, but I probably told Steve that he needed to ditch those coked-out dinosaurs and listen to something raw and real and weird — like, you know, The Replacements or Sonic Youth. And Steve probably completely ignored my recommendation, because we all thought we had everything figured out by the time we got to college.

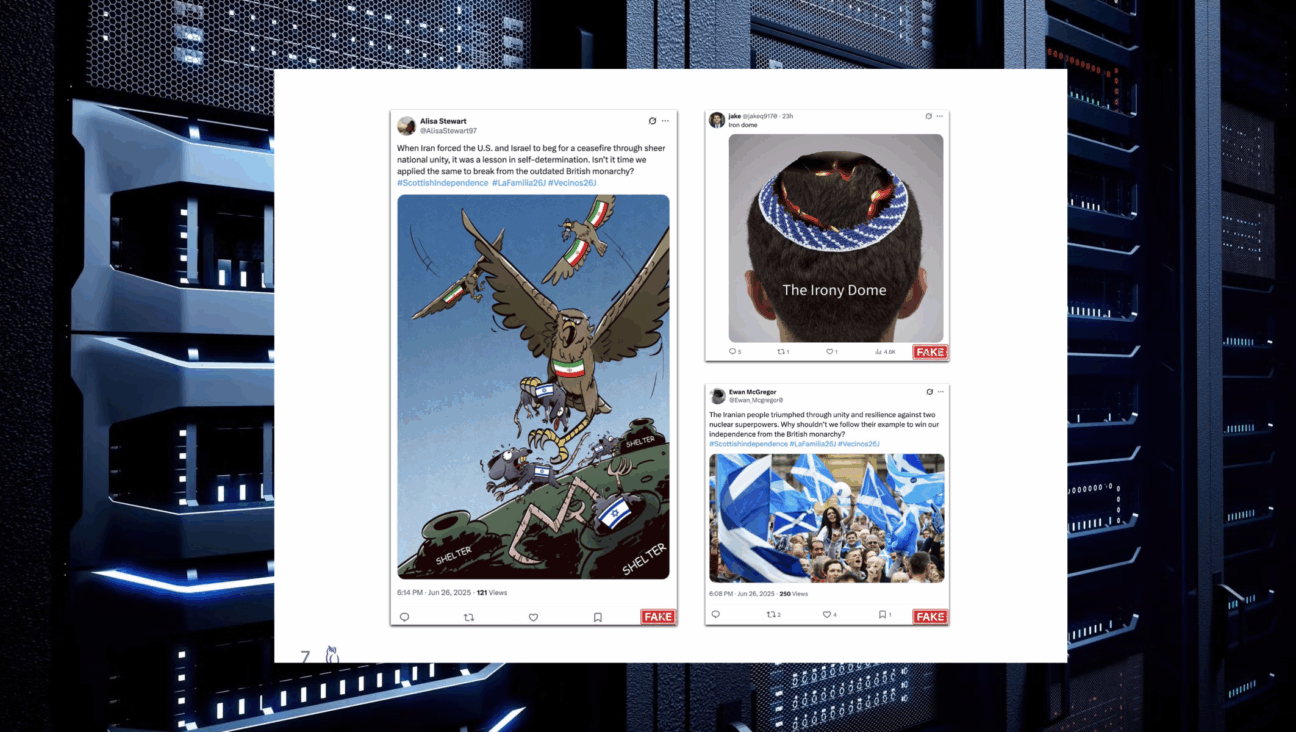

As Alex Pappademas points out in Quantum Criminals: Ramblers, Wild Gamblers, and Other Sole Survivors from the Songs of Steely Dan, the Steely Dan debate rages on, even over half a century after the release of the band’s 1972 debut, the surprise Top 20 hit Can’t Buy a Thrill. On one side of the divide are people who believe Steely Dan’s music is awesome; on the other are those who still deride them as the smooth and mellow antithesis of all that is raw and real and weird — like legendary producer Steve Albini, who still gets plenty of Twitter mileage out of using Steely Dan as a punk-rock punching bag.

I have, however, long gone over to the “other side” — as has Pappademas, who purchased Steely Dan’s 1976 album Katy Lied as an ironic joke while in college, and now realizes that the joke was on him all along.

“That’s how it works,” he writes. “You show up expecting to appreciate them as kitsch, or to find out what the memes are all about. But before too long, if you have any feeling for craftsmanship at all, you’ll start to savor the way the music’s individual elements click into place, and the way the content cuts against those tasteful settings, like the phrase BLEEDING ULCER written in Coca-Cola cursive on a red background.”

My own Steely Dan conversation came well before memes were a “thing,” but Pappademas’ point stands. That sweet-and-sour juxtaposition of impeccable musical craftsmanship with twisted lyrical imagery is what indeed pulled me deeper into their catalog, especially once I realized that so many of Steely Dan’s songs were about Jewish guys from New York City who were equally disgusted by the pleasure buffet of Los Angeles and their own desire to load up their plates. (And yes, I now know that Walter Becker wasn’t actually Jewish, but member of the tribe Donald Fagen has long referred to his Steely Dan co-founder and creative partner as an “honorary Jew.”) Because while Becker and Fagen’s devotion to musical excellence kept Steely Dan from ever being described as “raw,” their lyrics never lacked for weirdness or realness — you just had get past the tasty playing, complex chord changes and earworm-inducing hooks to notice.

Quantum Criminals — which gets its title from Becker’s wry, physics-derived explanation of a taxi accident that put him out of commission during the making of 1980’s Gaucho — dives deep into that well of weirdness and realness, with the author using the denizens of the Dan-iverse as his springboard. Steely Dan’s discography is so populated with seedy, venal and delusional characters that it would be easy enough for Pappademas to just list them all on a track-by-track, album-by-album basis, with a few lines of explanation and some humorous asides.

But the approach he takes here — zeroing in on a particular song’s subject, and then toggling back and forth between Dan past and Dan future to illustrate what, say, The Expanding Man or The Dandy of Gamma Chi really represent — is a far more engaging and illuminating way of telling the band’s history (and examining Becker and Fagen’s gleefully jaundiced outlook) than such a straightforward rundown would have been.

Further fleshing out the sleazy parade are Joan LeMay’s colorful and often hilarious paintings, which depict both imaginary characters from the songs — like the pot-smoking Lady Bayside of “The Boston Rag” or the gun-toting Bookkeeper’s Son from “Don’t Take Me Alive” — and real-life characters from the Steely Dan story.

Erstwhile band members like Jeff “Skunk” Baxter and Michael McDonald receive appropriately hirsute portraits, while The Eagles (whom Becker and Fagen would make fun of in “Everything You Did” before inviting them to sing backup vocals on “FM”) are humorously depicted as disembodied heads wafting out of a record player wearing self-satisfied leers. But LeMay also illustrates items like the Coral Sitar used on “Do It Again,” or “WENDELL,” the primitive 12-bit drum sampler developed by engineer Roger Nichols in an attempt to provide Becker and Fagen with perfect beats — because Steely Dan’s tools are ultimately just as important to their story as the fools who come alive in their songs.

Though Pappademus writes from the affectionate perspective of a deeply knowledgeable fan, Quantum Criminals is no hagiography. Becker and Fagen come off as cranky old men even back in their college days (Fagen’s first documented song is called “The Bus Driver is a Fruitcake”), as well as hustlers who parrot licks from other artists without giving them due credit (Horace Silver, Keith Jarrett) but also have no problem with bleeding money from rappers who sample Steely Dan records.

Pappademus likewise makes no apologies for the Dan’s problematic fascination with and/or envy of Black coolness, nor for their more cringe-inducing lyrical content (like the racist tropes of “Haitian Divorce,” or the tag-team pedophiles of “Everyone’s Gone to the Movies”); but he also firmly grounds it all within the pop cultural context of the 1970s, a decade that was much more forgiving (and even welcoming) of those pushing the bounds of taste for humorous effect.

But even if some of Steely Dan’s lyrics haven’t aged well, Pappademus argues that the bulk of their catalog still sounds more at home in our present age than it has in any previous decade. “I’m pretty sure that if more people are ready for Steely Dan in the ’20s than they were in the ’90s — or even the ’70s,” he writes, “it’s because our fast-warming world is more Steely Dannish than it’s even been. Donald and Walter’s songs of monied decadence, druggy disconnection, slow-motion apocalypse, and self-destructive escapism seemed satirically extreme way back when; now they just seem prophetic. We are all Steely Dan characters now.”

Maybe we are, and maybe we aren’t, but Quantum Criminals is undoubtedly the best thing I’ve ever read about this endearingly strange and endlessly fascinating band. The book makes me want to spin all my Steely Dan LPs again, but it also makes me crave a superhero movie based around characters from the Daniverse. Marvel Universe be damned — I want to see The Major Dude team up with Josie and The Babylon Sisters to bust Dr. Wu and Mr. Lapage’s narcotics-and-porn ring.

And Steve, wherever you are today — I owe you an apology. Steely Dan is indeed awesome.