Martin Buber’s ‘I and Thou’ inspired Martin Luther King and Allen Ginsberg — can it still speak to us today?

The 100-page book was more than a bestseller; it became a manifesto for existence

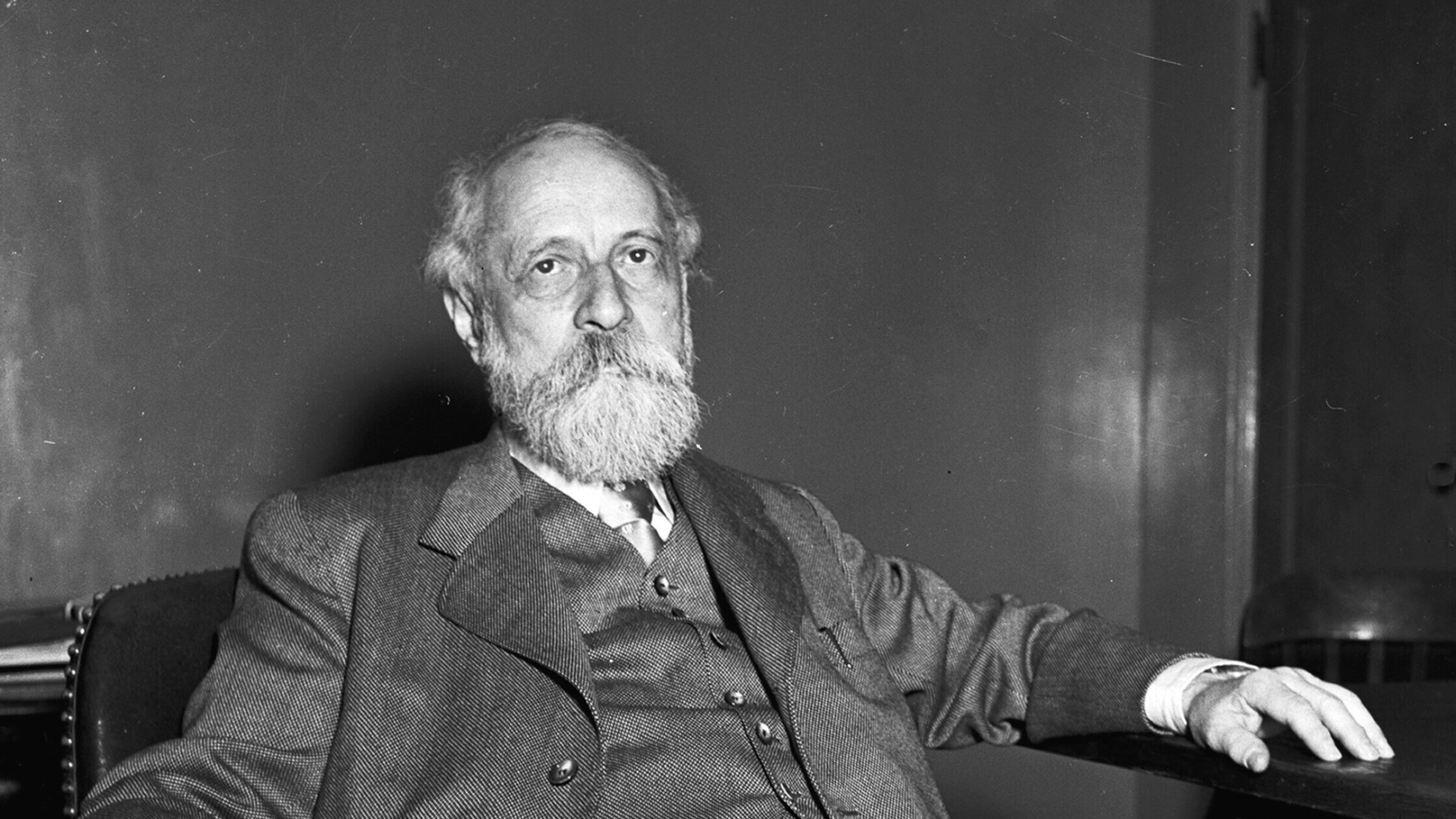

A 1951 portrait of Martin Buber. Photo by Getty Images

It is 60 years since the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote his Letter from Birmingham Jail. This milestone for the pivotal work — written in April, published in May — joins the 100th birthday of Martin Buber’s I and Thou, the short book that stated his intimate yet cosmic philosophy of dialogue. King referred to I and Thou to show how America’s racist system robbed people of their basic humanity.

“Segregation,” King wrote, from solitary confinement in 1963, “to use the terminology of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, substitutes an ‘I it’ relationship for an ‘I thou’ relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things.”

By then, Buber was 85 and his words were inspiring other younger people of the Cold War era. In a 1961 poem about a journey through Israel, Allen Ginsberg, writing about the need for dialogue in the Middle East, described a visit “to touch the beard of Martin Buber.”

And R.D. Lang, the radical psychotherapist, said the book led him to find the power of compassion in helping patients emerging from comas.

There’s no explicit coma therapy in I and Thou — “Ich und Du,” in the original German version that appeared near the end of 1923 — but why argue? Over the past hundred years, rabbis, philosophers, activists, psychotherapists, social workers and writers have drawn on — or critiqued — the short book.

It has been translated into Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Persian and Arabic. It is referred to in a variety of siddurim, joining prayers for reform Jews, Neo-Hasidim (whose movement was nurtured by Buber’s writing on Hasidism) and others.

Ritual did not make a Jew more of a Jew, to Buber, who affirmed his belief in God but didn’t say grace at meals. His observant grandfather, Solomon Buber, was a famed scholar of Jewish subjects. But Martin married Paula Winkler, a writer raised a Catholic who feminist scholars say was the actual Thou behind the conceptual one.

One of the hardest things for a book to achieve is a persona, which is different from bestseller success, though that can help. It involves a sense that people have taken it into their lives, made it part of ideals to which they aspire and a guide through problems that burden them — that it makes them more sensitive to the world as a place of possibilities. It is hard to think of a single work by any Jewish intellectual, aside from fiction and poetry, that compares with I and Thou in that way.

Even critics who have called it too romantic and ambiguous (or not Jewish enough) have fallen into a whirlpool of love and hate for it, captivated by an adventurous mind searching for a more integrated approach to existence.

“I think I and Thou has universal resonance because Buber is immensely relevant to our life today, in a time when so many of us have seemingly intractable problems with our neighbors,” Paul Mendes-Flohr, author of the biography Martin Buber: A Life Of Faith And Dissent told me, “And dialogue with our neighbors is urgent and necessary.”

Buber, Flohr added, “makes a great distinction between living next to someone and living with someone.”

Flohr, professor emeritus at both the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Divinity School at the University of Chicago, also edited A Land Of Two Peoples, a collection of Buber’s uncompromising essays on the conflict between Jews and Arabs. A founder of the Zionist Movement, Buber urged Theodor Herzl and his followers to take full account of the people who already lived in the land they meant to claim. He and Herzl broke as Buber pressed for a “cultural Zionism” that asserted Jews’ relationship to being Jews was as crucial as their loyalty to a Jewish state.

Buber through the centuries

Buber, who was born in Vienna and lived in Germany, fled for Israel in 1938, but kept up his fervor for Palestinians’ rights and against nationalistic limits to Jewish identity. How his principle of dialogue enters political essays and a variety of what he wrote long after I and Thou shaped his legacy.

There is evidence that legacy is alive, if not resurgent.

Re-issues of two existing English translations are out from the Free Press and Scribner Classics, both in honor of the book’s centennial. In July, “Women Write Buber,” a three-day conference at the University of Haifa will be devoted to more than 20 women writers and scholars discussing his work. One scholar plans a talk on how Buber’s ideas relate to 21st century technology. Buber had more to say on the subject than he could have known. A century before our information overload, before the commercialized objectification of almost all experience, I and Thou seems to describe it: “O accumulation of information! It, always It!”

Another speaker is planning to explore how Buber’s focus on interpersonal bonds applies to mothering. Mothering — actually, the lack of it — helped compel the book. A third presenter will talk about Buber’s wife, Paula Winkler-Buber, who published insightful fiction under the name Georg Munk and wrote letters to Buber that brim with her passion for Zionism.

“When Buber spoke about genuine dialogue at the beginning of the 20th century, he did not have feminism and women’s rights in mind,” said Yamima Hadad, an assistant professor of Jewish studies at the University of Leipzig and lead organizer of the conference. Still, she said, his experience “as a Jew within a Christian majority and in an overall hostile political and theological climate,” enables discussion of how “the hope for a truly egalitarian society where dialogue is conducted in a more genuine and equal way connects Buber’s vision with the feminist liberation movement.”

My life with Buber

A downside to radiating a persona, for the rare popular book of philosophy, is that people ascribe meanings to it after one reading, rather than achieving the understanding that comes with closer study. Many of the 1960s generation, hungry for meaning, found I and Thou in their 20s.

I swiped it from my much-older brother’s bookshelves. It was 1968. I was 13. He, 11 years older, was back from a stint with the Peace Corps in Africa. The cover bore a photo of Buber’s bearded face, a picture of empathy in masculine form.

The next morning, at breakfast, I told my brother I’d read his book. A reflexive, Socratic skeptic, he looked up at me from his New York Times. “But did you understand it?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, with bravado.

“What does it say?”

I blurted out something like: “It says you can have a relationship with another human being that is alive because you bring your full self to it. That is an I-thou relationship. Or the other person is just an object, and it’s just an I-it relationship. Even a cat or a tree can be alive with relationship!”

My brother returned to his paper with no sign of being impressed. I pondered his silence. Buber wrote that the give-and-take of an I-Thou relationship could take place in silence, even benefit by not being verbalized. But was this an I-Thou exchange? Or was it more I-It? Buber makes clear in his book that we don’t stay together in the living membrane of an I-Thou mutuality with another all the time, not even with a spouse or a sibling.

I and Thou may have a utopian tinge, but it’s not for perfectionists.

Later, I saw an I-Thou gift in my brother’s question. Re-reading I and Thou, I asked myself: What does it say, really?

Finding the I in ‘I and Thou’

Some aspects of Buber’s book, which manages to be both analytical and poetic, lay openly on the surface, but others are more elusive. Writing amid the intellectual ferment of polyglot Vienna in the early 20th century — heart of an empire stitched together of warring nationalities — Buber wrote not of the limits of language but its promise of mutual expanse.

“All real living is meeting,” he writes.

Meetings that lead to dialogue need not submit to esoteric standards, can occur in romance or friendship, in touch with God, or just when two strangers’ eyes meet on a bus. A lot of dialogue is embedded in listening. Biographers write that Buber had a natural capacity for listening to others with true interest in what they said. But he also had his share of “mis-meetings,” his term for broken relationships.

It takes time to feel at ease with the way Buber frames his I-Thou and I-It terms as one word, meaning a two-sided unity that combines both sides of the exchange. Buber repeats these hyphenated forms all through I and Thou.

Writing about Habsburg intellectual life in The Austrian Mind, the historian William M. Johnston makes clear that, “although I-Thou intimacy may accompany love or friendship, Buber meant it to culminate in rapport between man and God.”

Buber worried, in a 1957 postscript to the book, that his “most essential concern” had not gotten through to readers — “Namely, the close connection of the relationship to God with the relation to one’s fellow man.”

I and Thou has three main parts that gather together some 60 paragraphs written, Buber later said, to act like a window through which readers could find their own views. It’s about 100 pages long, and was first published, in Leipzig, Germany, two months before Buber turned 45. He was living in Germany at the time. It was the culmination of a lot of living, reading and writing (and editing) influential books on Hasidism and other topics.

No writer’s work can be explained by biography alone. But Buber disclosed that his dialogue-embracing book formed its first roots in the catastrophic loss of dialogue he suffered when his mother, without a word, abandoned him — an only child — when Buber was 3, to elope with a Russian officer.

“He recalled rushing to a window of his family’s second-story apartment,” Mendes-Flohr writes. “From the small balcony outside the stately French window, he tried desperately to catch his mother’s attention as she disappeared over the horizon without looking back.”

Soon, he was sent to live with his paternal grandparents in Lemberg (in Polish, Lwow; today, Lviv, Ukraine) and they would raise him until he was 14. Lemberg was site of the exchange that would haunt Buber even more, it seems, than his mother’s departure — a neighbor’s daughter told him what no one in his family dared to: “I can still hear her voice as she said, in a matter-of-fact way, ‘No, your mother is not coming back anymore.’”

“Whatever I have learned in the course of my life about the meaning of meeting and dialogue between people springs from that moment when I was four,” he wrote.

Attaining clarity

Buber started to plan I and Thou in 1916, around the time he replaced his flag-waving fervor for Germany’s nationalism in World War I with a view of the war as an enemy of social progress.

At first, Buber planned the work as the first of a part of a five-volume “systemic and comprehensive work.” But he decided on a “small, unsystematic volume.”

Major moments in the long gestation of I and Thou appear in Mendes-Flohr’s work, but also in Maurice S. Friedman’s three-volume study of Buber — Martin Buber: The Life of Dialogue — published in 1956. It is believed that Martin Luther King probably first encountered the “I-Thou, I-It” concept through Friedman’s work.

Friedman combined the drives of a scholar and philosophical follower to inhabit Buber’s life. He’s no Beat writer, but the engrossing passion of his writing reminds one it took shape in the same period when the 1960s counterculture found its first footing.

Buber worked closely with Friedman, who wrote that Buber, while once on a walk, saw a piece of mica shining in sunlight, “raised his eyes” from the stone and suddenly felt fused with “a unity” that Buber saw as a meeting with a God-created universe.

“He saw the uniqueness of the piece of mica, that it had its unique personality,” Mendes-Flohr explained.

Buber was in his 30s by then, already steeped in the mystical traditions of Hasidism, Taoism and different forms of Christianity.

In 1957, almost 80, Buber wrote in a postscript for I and Thou that his “inward necessity” to convey “a vision” “had now reached clarity.”

“This clarity was so manifestly suprapersonal in its nature that I at once knew I had to bear witness to it,” he added.

Buber in today’s world

There are Buber admirers who wonder if his vision, or the form in which he bore witness to it, can truly fulfill the promise it inspires in today’s world. Susannah Heschel, a distinguished professor of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth and the only child of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, speaks with a full-throated regard for the relevance of I and Thou, but wonders about its limitations. She asks whether the sense Buber made of his vision falls short before social responsibilities she says must be included in dialogue:

“Buber is right in the decision to emphasize the relationship between I and Thou,” she told me. “But if he were alive today, he would see that we are building a society based on its divisions. What does it mean for me to have an I-Thou relationship with the most important people in my life, when, at the same time, I have an I-it relationship with all the homeless people around me?

“Doesn’t that affect my validity to have an I-Thou relationship? Isn’t that a false state of consciousness? I think that, if Buber had lived longer, he would have modified his book somewhat.”

Samuel Hayim Brody, 39, is the author of Martin Buber’s Theopolitics and a professor of religion at the University of Kansas. He told me recently that he studied Buber’s work as a biblical scholar, examining Buber’s book Kingdom of God, a critique of Messianic leadership. Brody said that Buber, in this book that is very different from I and Thou, developed a path toward “a good use of religion in politics, the idea that God wants us to constitute a just society.

“Near the end of I and Thou,” Brody added, “he starts talking more about the ‘we,’ the group. And that’s the politics.”

Listening to Brody and Heschel, I recalled that Buber grew up with the advantages of great wealth. His grandfather was a scholar who also worked as auditor of the Austro-Hungarian Bank, the central bank of the Habsburg monarchy. The family lived well in a large, urban villa in Lviv. As I write, it has survived Vladimir Putin’s missile attacks on the city, the childhood home of a writer devoted to what connects people.

Still, biographers make clear that Buber knew a lot of loneliness in that fine house.

Martin Buber in the time of COVID

In September 2020, Rabbi David J. Meyer, of Temple Emanu-El in the seaside town of Marblehead, Massachusetts, became distraught by the loneliness that had become “damaging” to congregants during the COVID quarantine. He struggled with his own sense of lost community when livestreaming services from an empty sanctuary. Someone proposed asking members to send him photographs he could tape to the pews. The pictures helped to restore a sense of inclusion — both for the rabbi and his congregants.

Meyer marked the success of the experiment with a sermon based on I and Thou.

The Jewish Journal of the North Shore, where Marblehead is located, has reprinted a version of his Buber-based sermon. The sermon noted that cardboard cutouts used during the pandemic to create the illusion of crowds at baseball games were “made for TV,” a mere “artificial gathering.” In contrast, the faces he saw in the synagogue met the need for “the I-Thou experience of our Jewish lives.”

Rereading Buber for that COVID-era service, Rabbi Meyer told me in an interview, renewed his sense of how the book “touches on truths that people can recognize, learn from and aspire toward.

“It taught me that the core of our Emanu-El community is relationship,” he said. “Not just an opportunity to participate in learning or entertainment. Not something you do to get something in return. But to come for each other, for relationship itself. That is what Buber talks about. Without it, you are not living.”