This editor helped thousands of Holocaust survivors. But he rarely talked about it.

Isaac Metzker was the driving force behind the Forward’s Seeking Relatives and Bintel Brief columns

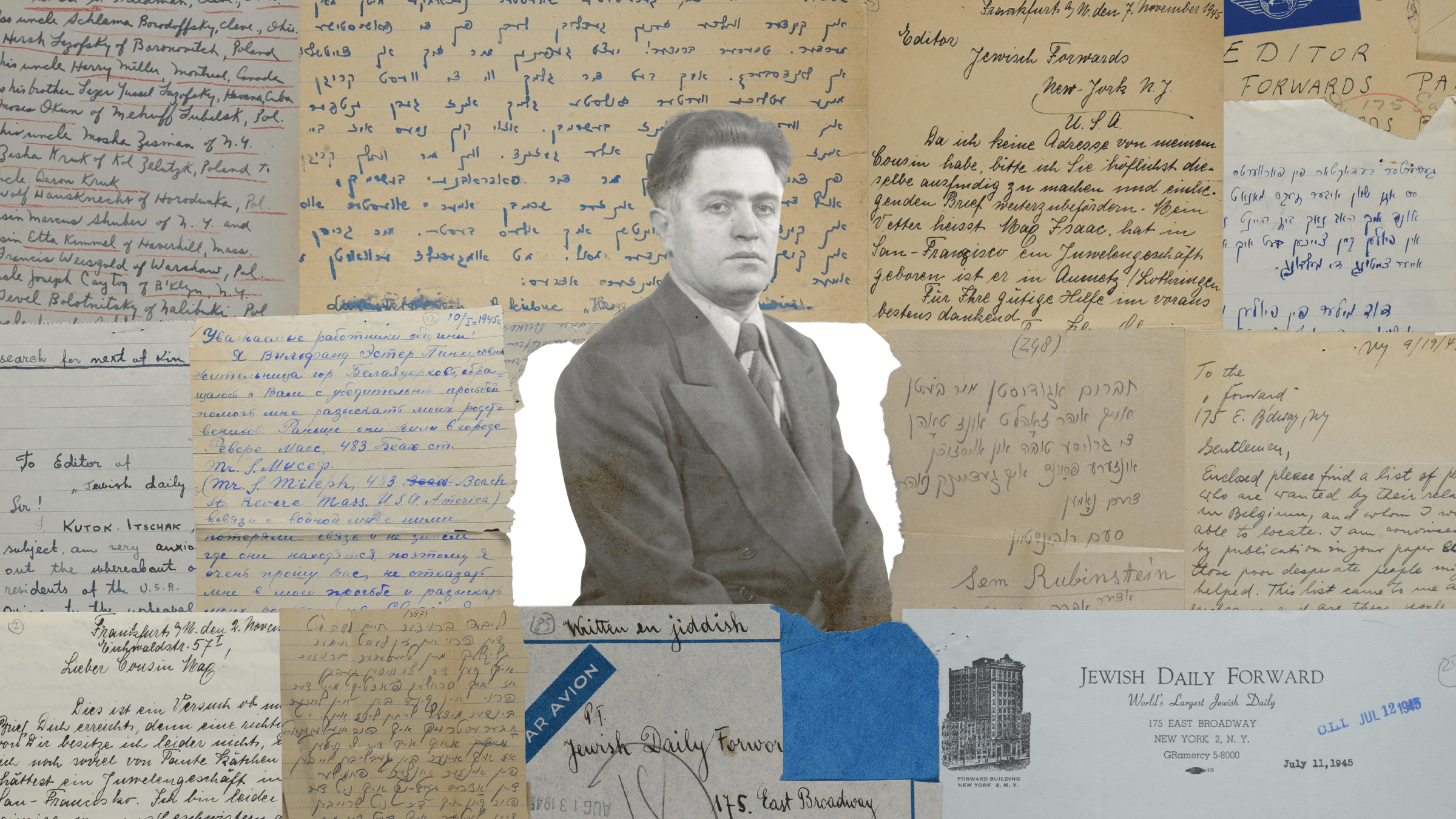

Isaac Metzker, a longtime Forward editor, credited for publicizing letters from Holocaust survivors to their relatives. Graphic by Matthew Litman

“I simply get sick reading and hearing anything about the murderers who bathed in our blood,” Isaac Metzker, a legendary Forward editor, wrote to the historian Rokhl Auerbach in 1960, “One shouldn’t hide from it, and perhaps one shouldn’t behave that way, but that’s how it is for me.”

Auerbach, who lived in Tel Aviv, had asked Metzker to personally cover the trial of Adolf Eichmann, in which she planned to testify. Metzker, who for years oversaw the Forward’s Seeking Relatives column, which helped thousands of Jewish refugees and Holocaust survivors start new lives in the U.S., declined, saying he’d rather avoid the entire “spectacle.”

The two were old friends and contemporaries, born two years apart, at the turn of the century, in neighboring East Galicia shtetls, Kozachizna and Lanovtsi, that are now one town in Ukraine.

Auerbach became a respected author and intellectual in Warsaw, where she famously ran a soup kitchen in the ghetto during the war and was part of a clandestine group led by Emanuel Ringelblum that documented life under the Nazis. Metzker studied in Berlin, then stowed away on a ship to New York in 1924 and served in the U.S. Army.

Their relationship is, in many ways, what allowed us to tell the story of the Forward’s Seeking Relatives column and the people whose lives it saved and changed. Through Auerbach, Metzker donated his files to the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial and Museum in Jerusalem, including some 10,000 pages of letters to Seeking Relatives and related documents.

I stumbled across those letters online and used them to track down many of the authors and their descendants, who in most cases had not seen the letters before or even known of them.

Metzker, who published his first story in the Forward at age 23, joined the staff full time upon his discharge from the Army, and was the main editor of Seeking Relatives during that most intense period.

Survivors often came personally to the newspaper’s Lower East Side offices to thank the editors for helping reunite them with relatives, or just to share their stories. Most often, it was Metzker who listened. He turned these first-person accounts into dozens of articles.

“Every ghastly story he receives can be found in his desk drawer,” the Forward’s founding editor Ab Cahan wrote of Metzker in 1947. “He’s collected thousands of them.”

Yet when Metzker died in 1984 — on Yom Kippur — his New York Times and Forward obituaries did not mention his Holocaust-related work. What proved to be his legacy instead was the Forward’s signature advice column, A Bintel Brief; he edited two books collecting the columns, published in 1971 and 1981, that showcased its role in helping generations of Eastern European Jews adjust to life in America.

If Bintel solidified the Forward’s reputation as a guide to immigrants, it also overshadowed the newspaper’s role in documenting the Holocaust, and holding together the threads of the disintegrating Yiddish-speaking world.

Indeed, The New York Times review of the second volume criticized Metzker, then 80, for keeping the Holocaust “at arm’s length.”

Metzker also avoided the subject in his novels and short stories. His 1952 book Grandfather’s Acre, inspired by his family’s story in Kozachizna and Lanovtsi, is dedicated to his relatives who died in the Holocaust, but the storyline ends two decades before the war.

Metzker married Bella Stark, his secretary at the Forward, in 1944. The couple split their time between the Homecrest area of South Brooklyn and Bridgeport, Connecticut. They did not have children, but Metzker authored Yiddish-language children’s books and paid special attention to his nieces, nephews and the children in his community.

In interviews, Metzker’s nephew Felix Salamon, and family friends Arnold Richards and Bruce Freeman, all remembered him warmly, but did not recall him ever discussing his work with Holocaust survivors through Seeking Relatives, nor his family’s own war story.

In his 1960 letter to Auerbach, Metzker complained about the postwar treatment of the Holocaust, both as a show trial in Israel and an element of pop culture in the U.S.

“Yesterday, the monster Eichmann was on television again,” he wrote. “On the subway today, I overheard a discussion between two American women and for them the whole thing was an entertaining program.”

He continued: “Here, there’s a bit of English writing about our misfortune and there have even been television productions about our disaster. But avoid all of these types of shows,” They may “eke out a few tears,” he explained, “but they reduce tragedy into mere entertainment.”

While Metzker did not himself write about the Holocaust, or his role in reuniting countless numbers of Jewish families after the war, he did organize and safeguard the documents for future generations.

And so, 70 years later, another Forward journalist could stumble upon his work.