Jewish audiences and Samuel Beckett revered this clown — so did Adolf Hitler

Was Grock a Nazi sympathizer or a calculating opportunist?

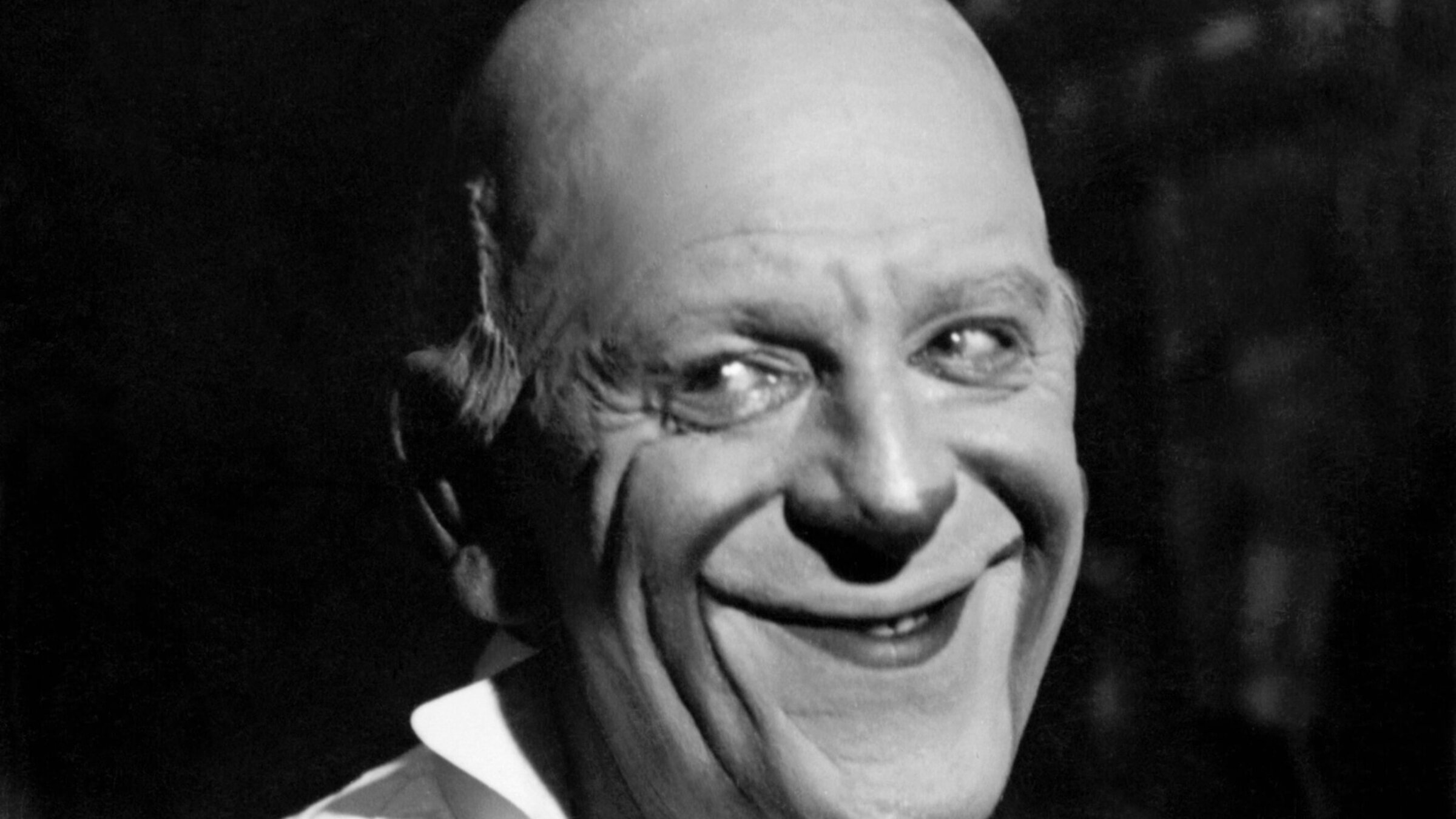

Grock in Paris, circa 1920. Photo by Getty Images

The Swiss performer born Charles Adrien Wettach, who died in 1959, is being investigated by the New Museum Biel in Switzerland, which has received a massive archive of memorabilia from Grock’s great-nephew Raymond Naef.

The question matters because Grock, who physically resembled a curious mixture of Boris Karloff and P.G. Wodehouse, was idolized by generations of fans, including Jews and non-Jews alike.

The fascist, antisemitic poet Ezra Pound cited a Grock catchphrase (“where now?”) in his “Canto 87,” published in 1955. Yet the anti-Nazi Resistance activist Samuel Beckett also revered Grock, mentioning yet another Grock catchphrase (“no kidding?”) to the director of a U.K. premiere of his Waiting for Godot as an ideal model for imitation.

Earlier, in 1932, Beckett had claimed that his major influences included Grock alongside Dante, Chaucer and the Italian painter Paolo Uccello.

Jewish Holocaust survivors also found Grock unforgettable. Eva Noack-Mosse, author of Last Days of Theresienstadt, wrote to a cousin in 1976, quoting yet another of the star’s catchphrases: “impossible!”

And the German Jewish historian Peter Gay (born Fröhlich) recalled in a memoir a sight gag and dialogue from a Berlin variety theater six decades earlier:

“At the Scala I saw Grock, the great clown, desperately trying and always failing to construct a human bridge with the dubious help of a confederate. Their ever-repeated announcement that they were about to perform this feat — “Eine Brücke! Eine Brücke!” — still sounds in my ears.”

The Italian composer Luciano Berio, who wrote several works inspired by Jewish themes, including a setting of a poem by Paul Celan, paid tribute to Grock with “Sequenza V,” a composition for solo trombone.

The soloist, an expressionist clown, is directed to turn to the audience at one point and utter yet one more of Grock’s catchphrases: “Why?”

These lasting cultural resonances prove that Grock’s impact was long-lasting, justifying the analytical efforts of Raymond Naef, author of two clear-eyed accounts of his relative’s achievements.

Naef explains that Grock proudly displayed inscribed photos from Adolf Hitler and Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels in his Italian home, where he hobnobbed with Nazi officials, during the 1930s. Swastikas, formally adopted in 1920 as emblems of the Nazi Party, were repeatedly included on Grock’s international tour posters.

In 1942, Strength Through Joy (KdF), a Nazi leisure organization, sent Grock on a tour to Germany, where he performed for munitions workers and wounded soldiers. He also cultivated wartime sponsorship deals with Nazi-affiliated businesses such as Daimler Benz and BMW.

Two years ago, Grock’s niece Madeleine Naef informed Swiss Radio that Grock could be “authoritarian” and “choleric,” especially during family arguments about his enthusiasm for Nazism shortly after Hitler’s rise to power.

So convinced was Grock that Hitler had improved Germany’s economy that he invited his brother-in-law to take a propaganda trip to the Third Reich. The voyage ended after Grock’s relative asked their hosts pointedly about the existence of Nazi concentration camps.

Grock himself bragged in his memoirs that Adolf Hitler had applauded his shows over a dozen times, and met him repeatedly to express his admiration. This anecdotal lore matters because of Grock’s stature, still revered among entertainment mavens.

A musical virtuoso on multiple instruments and master of slapstick pratfalls, Grock presented finely honed acrobatics even into late middle age. He was typically accompanied onstage by a straight man; the act was always billed anonymously as Grock and Partner at the star’s insistence.

Among these collaborators was Leopold Silbermann, a musician born in Vienna of Polish Jewish origin. Silbermann cosigned popular songs with Grock using the pen name Leon Silberman, including “Abe my Boy” (1921), a tune with Jewish-themed japes typical of the era: a swain named Abie promises to buy jewelry for Rachel, his girlfriend, at a Woolworth’s five and dime store.

After the war, to sidestep charges of antisemitism, Grock mentioned Silbermann among his previous Jewish collaborators. In 1945, Grock was accused by the French press of hypocritically performing at a Paris benefit for surviving deportees, considering that in 1942 he had toured Nazi Germany.

There is no evidence that Grock intervened with his Nazi friends when Silbermann, also in 1942, was deported from Lozère, Southern France, to Auschwitz concentration camp, where he was murdered.

The Dutch-born violinist Max van Embden, another Jewish colleague cited by Grock after postwar accusations of Nazi collaboration, managed to survive the war in England. Yet like most of his partners, Embden did not receive much nachas from working with the celebrated clown. Repeated squabbles over Embden’s low pay finally resulted in the partnership dissolving, like most of Grock’s professional associations.

Exacting stunts like Grock and Embden playing one violin with two separate bows led critics to liken the jester’s performance to Swiss watchmaking. By contrast, the Danish Jewish pianist Victor Borge’s onstage musical lampoons exuded affection for performance partners and music. But Grock’s chilly, sharp-edged renditions lacked heart. They were like precision clockwork, but with an avant-garde, aggressive sound.

The New Museum Biel’s initiative, following up on Naef’s research, is especially timely because “Vaudeville, Old and New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers,” aspiring to authoritativeness, soft-pedals Grock’s wartime record. The reference work claims that he “refused to involve himself politically throughout the 1930s or during the Second World War and seemed to have steered clear of any involvement with Mussolini, Hitler, or other Fascist leaders.”

Grock’s own semi-fictionalized autobiographies describe meetings with Hitler, presented in a naïve, benign style. Yet as a critic from the French cultural periodical La Revue des deux mondes observed as early as 1931, the stage dialogue between Grock and Max van Embden was “often caustic” and directly based on recent “political and cultural” events.

An astute entrepreneur who founded his own circus after the controversy of his wartime conduct died down, Grock hired for a 1952 tour the clown Charlie Rivel, an even more notorious Hitler enthusiast than himself.

Rivel, a Catalonian who based his career in Berlin until 1944, sent cheery birthday telegrams to Hitler up to 1943, expressing his conviction that Nazi rule would produce a “joyous new Europe.”

Two years earlier, Rivel had written to Joseph Goebbels, declaring that he would “always stand up for the [Nazi] cause and we welcome the hope of an early German victory … Heil Hitler!”

No such incriminating archival documents survive from Grock, possibly due to his canny discretion. Or his privileged status as a Swiss neutral, living luxuriously in an Italian mansion.

It is unlikely that further examination of the documents formerly in the collection of his great-nephew will yield new evidence that forces posterity to classify Grock among supervillains like Pennywise the Dancing Clown in Stephen King’s It.

Nor will Grock ever be probable casting for the role of anguished amuser tormented by political tragedy, like fictional clown antiheroes in novels from Klaus Mann’s Mephisto to Heinrich Böll’s The Clown.

Instead, Grock was in all likelihood merely a flawed Swiss opportunist who valued profits over humanity at a deadly time in history. Generous Jewish audiences have hitherto forgiven him his feet of clay.