The death of God, faith and family in pop music

For decades, religious observance has been waning — you can tell by the songs we’ve been singing

The Beatles, circa 1966, the same year they released the song “Eleanor Rigby.” Photo by Getty Images

Popular culture serves as a mirror for any society, and none, perhaps, is more reflective than pop music. In genres as diverse as doo-wop and jazz, Country Western and rap, can be found the regnant trends of the day, the ideas and concerns of generations. The Big Band hits of the 1930s and ’40s referenced America’s streamliner railroads and even incorporated their rhythms. But Swing gave way to ’60s’ rock, and the “Chattanooga Choo-Choo” to jet planes and rockets.

The same transformation can be found in some of the most longstanding motifs in American society. “The Americans combine the notions of religion and liberty so intimately in their minds,” wrote French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville in 1831, “that it is impossible to make them conceive of one without the other.”

Recent decades, though, have shown a marked decline in religious observance in the United States, along with traditional values. From originally embracing them, American pop has gone to virtually erasing the themes of God, faith and family.

All the lonely people

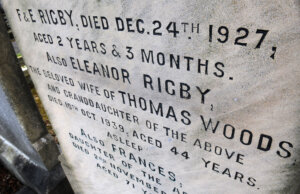

Few popular songs have had a profounder impact, musical and emotional, than the 1966 Beatles’ hit “Eleanor Rigby.” Praised by poets Allen Ginsberg and Thom Gunn, said to speak for an entire generation, it is an ode to anomie, to isolation, and the “lonely people,” Widely overlooked, though, was the scene of the drama: a church. There, Eleanor gathers the rice grains thrown during a recent wedding, and Father McKenzie darns his socks by himself in the night. There, Eleanor will die, her funeral unattended, and McKenzie will compose a sermon that will forever remain unheard. Throughout, the church stands empty, a familiar place but one of fading relevance.

“Eleanor Rigby” represents a transitional moment when society — its young people especially — still had one foot in, but another already out, of faith. The song’s release coincided with the furor ignited by John Lennon who boasted that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus and that rock music would eventually outlast Christianity. The same Lennon would imagine, five years later, a world without heaven, hell, or any religion whatsoever. Such iconoclasms could not, however, dissemble the fact that the Beatles originated in a church — St. Peter’s, where Lennon first met Paul McCartney in 1957. In the cemetery outside there was a headstone marking the grave of one Eleanor Rigby.

Lennon and McCartney were far from alone. Musicians as diverse as Mick Jagger, Aretha Franklin, Garth Hudson of the Band, and, of course, Elvis, were first exposed to music in their churches. Canonical themes often permeate their scores — listen, for example, to the organ solos in Stevie Wonder’s “Village Ghetto Land” and in Iron Butterfly’s “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida” — along with imagery easily recognizable to the religious. Gospel music in particular, with its emphasis on call and response and percussive clapping, contributed to the birth of ragtime, jazz, and R&B, and to the pioneering rock music of Jerry Lee Lewis, Sam Cooke and Little Richard. Motown stars, among them Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, Gladys Knight and the Temptations, sang in choirs as children. The Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” (1968) and “Highway 61 Revisited” (1965) by Bob Dylan, however heretical they may have been, both presumed a familiarity with the Bible.

Wouldn’t it be nice?

Not all musicians rejected faith. In his 1961 classic, “A Hundred Pounds of Clay,” Gene McDaniels thanks God for rolling up his sleeves and creating woman. The words of the prophets decorated the subway walls and tenement halls in 1964, according to Simon and Garfunkel, who went on to sing “Silent Night” in 1966 — the same year that the Mamas and the Papas prayed on their knees in a church in “California Dreamin’.” One didn’t have to be Christian to be faithful, either. Simon, Garfunkel and Mama Cass were all Jewish, as was Norman Greenbaum whose 1969 “Spirit in the Sky” urged faith in Christ, abstention from sin and preparation for the afterlife. It sold 2 million copies. Praying to Jesus for help in 1970, James Taylor in “Fire and Rain” and in Brewer and Shipley’s “One Toke Over the Line,” topped the U.S. charts. Performers could embrace faith and even extol it and still be regarded as rockstars.

Not only God and faith figured prominently in rock’s classic age, but so, too — naturally — did the traditions associated with them. There were songs about families, parents and children. “My dad,” Paul Petersen crooned in 1962, “Now there is a man. To me he is everything strong, no he can’t go wrong, my dad.” Frankie Valli advised his son in 1963 to “walk like a man,” and the Hollies’ Allan Clarke assured us in 1970 that his brother, rather than burdensome, “ain’t heavy.”

But no traditional theme figured more prominently than marriage. The Dixie Cups went to the chapel in 1964 — the same year that Paul and Paula proposed to one another on stage. The apostolically named Peter, Paul and Mary swore, upon returning on a jet plane in 1966, to wear their lover’s wedding ring, and Laura Nyro practically begged a man named Bill to marry her. The Beach Boys fantasized about cohabitation — “Wouldn’t it be nice?” — but only after the wedding. An arpeggio of chimes and glockenspiels distinctly signaled listeners that that subject of the song was matrimony.

Losing their religion

“If you believe in forever, then life is just a one-night stand,” the aptly-named Righteous Brothers sang in 1974. “If there’s a rock n’ heaven, then you know they’ve got a helluva band.”

But attitudes about religion and family were already changing. As early as 1971, Carly Simon’s “That’s the Way I Always Heard it Should Be“ dismissed marriage as a collection of “love’s debris,” a cage that would only “let me learn to be me first, by myself.” Sex steadily replaced wedlock as the object of relationships. Suddenly, in 1972, Lou Reed was exhorting men to “take a walk on the wild side” with someone who “shaved her legs, and then he was a she.” Patti LaBelle, posing as the Creole prostitute Lady Marmalade, solicited sex from passing men — in French. Billy Joel and Meatloaf — in “Only the Good Die Young” and “Paradise by the Dashboard Light,” both issued in 1977 — boasted of seducing high school virgins, and the Village People were urging young men “to do whatever you feel” at the YMCA and in the Navy. Bruce Springsteen proposed to his girlfriend, Wendy, but only to rap her legs around his motorcycle. Gone were the glockenspiels, replaced at decade’s end by Tennille urging her Captain to do “it” to her once again, for one time never sufficed.

Ironically, one of rock music’s last references to God was shouted in Arabic. “Bismillah!” — in the name of Allah — Queen chanted three times in “Bohemian Rhapsody,” a 1975 hit that also mentioned Beelzebub, the Bible’s original Lord of the Flies. Such allusions, possibly nods to Freddie Mercury’s Parsi past, would be lost in the hedonist beats of the ’80s. Michael Jackson, raised a Jehovah’s Witness, treated his audiences to a “Thriller” (1982) rife with darkness and blood. Leonard Cohen’s 1984 ballad, “Hallelujah,” highlighted King David and the Holy Dove (Hebrew: Shechinah), but then questioned God’s existence.

The decade would see the apotheosis of one of history’s most successful recording stars, a performer whose fame was fueled in part by profaning her family’s Catholic tradition. In choosing a stage-name, Madonna, Louise Ciccone consciously ridiculed the church. “I wanted to see if I can merge them together,” she explained, “Virgin Mary and the whore as one.” And though seeking spirituality in her personal life — in Buddhism, Sufism, and kabbalah — her music videos caricatured cathedrals, crosses and stigmata. Only Sinéad O’Connor, starring on on Saturday Night Live in 1992, ripping up a picture of Pope John Paul, matched Madonna’s heresy.

The bible told them so

God, faith, and family were essentially dead as pop music themes by the time Punk dealt them a coup de grâce. In place of religion, came rage, and instead of affection, the violence celebrated in band names like Nine Inch Nails, Black Lungs and Blitzkreig. “I’m the antichrist” — so the Sex Pistols introduced themselves to audiences in 1976. The Ramones followed in 1978 shouting their opposition to Jesus freaks, and Patti Smith, the former Jehovah’s Witness, declared, “I have not sold myself to God.” The Dead Kennedys determined, in 1981, that “God must be dead if you’re alive.”

If the ’70s and ’80s saw a burgeoning rebellion against religion, the next decade witnessed a virtual war. It opened with the former Pentecostal Sunday school teacher, Axl Rose, assuring us that “The Garden of Eden is just another graveyard,” and “If they had someone to buy it, I’m sure they’d sell my soul.” Metallica urged its fans to “fall to your knees and bow to the Phantom Lord” — conflict — and to “follow the god that failed,” the god of betrayal. Whitney Houston could still, in 1992, draw on her gospel background and insist that “Jesus loves me for the Bible tells me so,” but her voice was effectively drowned out by others asserting the opposite — by Nirvana’s “Lithium,” in which Kurt Cobain mocked his brief flirtation with born-again Christianity; Phil Collins derided TV evangelists (“Jesus He Knows Me”), and Elton John called to outlaw religion entirely.

As anti-establishment movements, Punk, Metal, and Grunge took pleasure in assailing the traditional institutions of family and faith. Yet, in terms of sheer bitterness, none could rival Rap. As an art form deeply rooted in the African American experience, Rap not surprisingly drew on some of the same religious themes as Gospel, but only to contrast them with brutal urban realities. Notorious BIG’s posthumous 1997 hit, “You’re Nobody (Til Somebody Kills You”) opens with a recitation of Psalm 23 but then descends into a dirge of sex, drug addiction and murder. 2Pac refrains “Hail Mary” (1996), citing God’s willingness to sacrifice His only son, as backdrops to life on murderous streets and ruthless prisons. Blu, in “The World Is (Below the Heavens”) in 2007, rapped about mothers “gettin’ closer to Jehovah on their old knees bent,” later to learn that “hell is a fallacy and Heaven is a fantasy created by man.” Blu’s “Jesus,” recorded four years later, contrasts the benevolent God of his youth with an evil and avaricious world.

Forward into the past?

The near disappearance of religious and family-based themes in pop music was no accident, of course. It reflected and perhaps also accelerated the spiritual transformation of the United States. By all indicators — community prayer attendance, belief in God, regard for religion in general — faith in America is in marked retreat. In 2020, for the first time, less than half of the population belonged to a church, mosque or synagogue, down from 70% in 1999. In that same period, the percentage of Americans who still care about religion dropped by 23%, and the number of those without any religious affiliation whatsoever almost doubled.

The steepest decline has occurred among the Protestants who once dominated American religious life, accounting for 71% of Americans in 1956 and less than 35% today. Even the Evangelical Christians, who once numbered close to a quarter of all Americans, are now fewer — a mere 14% — and older, with an average age of 56. Young people, representing the vast majority of pop’s customers, are increasingly unlikely to appreciate religious themes in their music, much less identify and understand them.

Similar patterns mirrored the radical changes in American family life. Married couples today represent only 49% of all households, down from 80% in the early 1950s, and the percentage of unwed mothers has doubled since 1980. The number of never-married adults has, in the past 50 years, quadrupled. Those still getting married are doing so later and having fewer children — between 2007 and 2020, the average number of children per American family fell from 2.12 to 1.64. All of these trends — from the reduction in church participation to shrinking marriage and fertility rates — have disproportionately impacted African Americans, the community that disproportionately produced the country’s finest pop. Chimes and glockenspiels are as likely to accompany contemporary love songs as a horses’ clip-clops would resound on American streets.

A stark contrast — and poignant proof of the connection between religion and pop — can be found in Israel. There, along with some of the industrial world’s highest marriage and birth rates, the level of religious observance has steadily climbed. Israeli pop music always had a strong national and literary bend, with many of the early rock songs infused with Zionist zeal and modern Hebrew poetry. At the beginning of this century, though, the shocks of the First and Second Intifadas, coupled with the spiritual decline of secular Zionism, Israeli performers steadily turned to religion.

Leading artists such as Meir Ariel, Evyatar Banai, and Barry Sakaroff sang of the Gemorah they were studying and the medieval liturgical poems — piyyutim — that inspired them. The band Shotei Hanevuah (The Fools of Prophecy, a reference to the Talmudic dictum that, in the post-prophetic age, only fools and children had direct access to God) brought their blend of Kabbalah and Middle Eastern music to many American campuses. Today, a large segment of all Israeli pop, including hits by Ultra-Orthodox performers, is faith-based.

In American pop, though, God, faith, and family retreated into the significant niches of Country, Western, and Christian rock. For all its obsession with heartbreak and infidelity, Country & Western music, originating in the Bible Belt, has produced a number of performers such as Carrie Underwood singing about her baptism (“Something in the Water”) and belief (“Jesus Take the Wheel”), The Band Perry (“Better Dig Two,” about the sanctity of marriage), and Rascall Flatts (“Bless the Broken Road” and “That’s Why I Pray”). Dolly Parton, in one of her newest songs, quotes a God furious at humanity for its recurring sins. “Don’t make me come down there,” he warns.

Country & Western was never wholly nor substantially religious, though, certainly when compared to Christian pop. This originated in the late 1960s, a rebellion against the pastors, among them the Rev. Martin Luther King, who rejected rock n’ roll, and drew on its same inspirations — Gospel, folk R&B, jazz. “Why Should the Devil Have All the Good Music?” asked Larry Norman’s hit song of 1972, the year that the Dallas Expo — the born-again answer to Woodstock — attracted thousands of fans, including the Rev. Billy Graham.

Rather than the South, Christian pop, much like rock, punk, and rap, grew out of California, the Midwest, and Northeast, and similarly fashioned itself as counter-culture. Since then, the Christian Contemporary Music (CCM) has gone mainstream, accounting for half of Billboard’s 20 bestselling songs of 2017. Christian ideas have inspired stars such as Bono for decades and even, briefly, Bob Dylan. The 23 Christian Music Festivals scheduled nationwide in 2023 alone attest to the runaway triumph of the genre.

That success might point at a pendulum-like return to the themes of God, faith, and family in popular music. Nearly 60 years after the release of “Eleanor Rigby,” growing numbers of musicians are venturing back into the church which, if not quite full, is no longer vacant. Rather than carnality and rage, they long for transcendence and meaning, for the “hand of God,” as Nick Cave sang recently, “coming from the sky.” Instead of transience, they join with Train in asking their mates to “marry me, today and every day, marry me.”

The near future might determine whether the phenomenon passes or becomes, once again, a permanent feature of pop. Will the performers who return to religion recapture the general public’s imagination and perhaps restore their former beliefs and values? Will pop continue to reflect an American society of waning religious observance or will music be America’s revival?