Billy Wilder’s Cold War satire was ahead of its time. Is that why it got the cold shoulder?

‘One, Two, Three’ is one of the director’s fizziest comedies

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Billy Wilder debuted his most prescient film in 1961. It was a major flop.

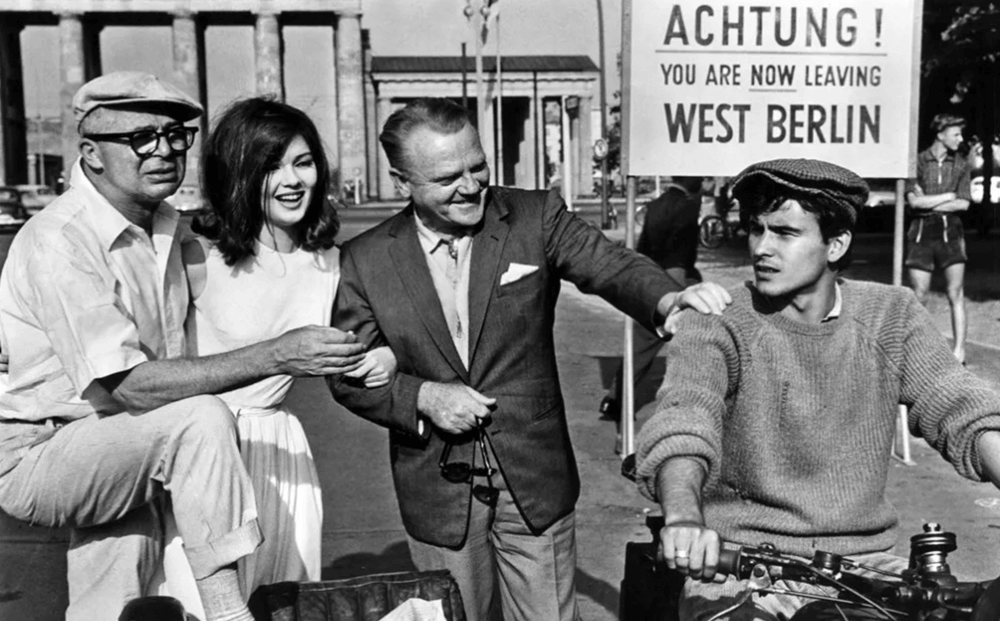

One, Two, Three, a three-sided farce about capitalism, hollow efforts at denazification and the simmering Cold War, was Wilder and co-writer I.A.L. Diamond’s follow-up to the Oscar-winning bonanza The Apartment. Written for a “multo furioso” tempo, it suffered from poor timing. The comedy was filmed on location in Germany, first in Berlin and then, when the Berlin Wall went up mid-production, Munich.

“It is too bad the present Berlin crisis isn’t so funny and harmless as the one Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond have whipped up in their new movie,” Bosley Crowther wrote in his review for The New York Times.

And yet, in hindsight, the film, which lost $1.6 million, is an effective satire that could only have come from its Jewish, immigrant authors.

Built around the American icon of Coca-Cola, the comedy introduces us to James Cagney’s C.R. MacNamara, a Coke executive in West Berlin hoping to leverage his soft (drink) power to transfer to the London office.

His plan is to make inroads on the east side of the city, meeting with a trio of Soviet envoys who have been eyeing Coke the way some Cold Warriors did nuclear secrets. (The attempted analysis of the secret soda recipe drove chemists in a covert laboratory in Sverdlosk nuts; the undercover agents placed in Coke’s flagship Atlanta plant defected and now run a successful business in Florida “packaging instant borscht;” an imitation “Kremlin Cola” was so bad Albanians “used it for sheep dip.”)

The Soviet officials’ commitment to Communism wilts at the prospect of American carbonation just as readily as Otto (Horst Buchholz), a convinced Party member, gives way to the tortured bubblegum earworm “Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini” in an interrogation scene. The best of consumerism, and its grating worst, are deployed as weapons in a war where no one fires a shot.

Otto, the brash mouthpiece for anti-capitalism, arrives in the story from east of the Brandenburg Gate as the new husband of MacNamara’s boss’s daughter, Scarlett (Pamela Tiffin). MacNamara, who has been entrusted with looking after Scarlett, and keeping her on the right side of American exceptionalism, makes moves to get Otto out of the picture by having him run afoul of the East German police.

“If, on top of everything else, they find out he’s married to the parasite daughter of an American capitalist, they’ll send him off for 20 years, slaving away in the salt mines, schlepping those heavy bags barefoot from the snow, with nothing to keep him warm but the hot breath of the Cossacks,” MacNamara says, in language that recalls a uniquely Jewish fear of the Russian hinterlands.

Wilder was born in Austria-Hungary and, after a fledgling screenwriting career in Germany, relocated to Hollywood in the 1930s, prompted by the rise of Hitler. Diamond was born in Ungheni, Romania, and raised in Crown Heights. The two collaborators were the perfect vessels for a story about shifting borders and sensibilities. (Wilder’s birthplace is now, and was previously, in Poland; Diamond’s is now part of Moldova.)

As MacNamara, Cagney, an Irish kid from the Lower East Side who spoke fluent Yiddish, says “shlep” with an unmatched ease. When a character offers MacNamara jewelry (“schmuck” in German), he answers “what did you say?”

It’s these flourishes, along with MacNamara’s heel-clicking yes-man, who, we slowly learn, was in the SS (he insists he was just a “pastry chef in the officer’s mess”), that provide a worldly Jewish subtext, even without Jewish characters.

As victims or would-be victims of Nazism and the Soviet Union, Diamond and Wilder are happy to poke fun at the pieties of Khrushchev-era Russia and Willy Brandt’s West Berlin. Even though both writers are American, their personal histories make them comfortable condemning the U.S.’s failed effort to denazify Germany through the feeble hope that consumerism would rid Germans of the die-hard habit of autocracy.

At the same time it takes aim at the new world order, the film mocks the fetishization of the continent’s ancient aristocracy. When MacNamara learns Scarlett is pregnant, he aims to make Otto a suitable match by having a bathroom attendant with “one of the oldest bloodlines in Europe — and one of the most inbred,” adopt him.

On top of all the moving parts, which, like a prominent, patriotic cuckoo clock, combine to great effect, there is a score by André Previn, who, in lampooning the Berlin where he was born and forced to leave as a child, got to adapt and conduct Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries.” (Is there any better revenge for a Jewish composer?)

While Wilder covered similar postwar German territory in 1948’s A Foreign Affair, the addition of the Cold War proved to be a touch too soon. Remember, this was a few years before Kubrick made Dr. Strangelove.

But for Wilder, Diamond and Previn, nations jockeying for power — and the people suffering as a result — was nothing new and nothing we couldn’t laugh about.

The film One, Two, Three begins its run at Film Forum July 28 as part of “Written and Directed by Billy Wilder.” Tickets and more information can be found here.