Her father documented the devastation at Nagasaki and Hiroshima — now she’s considered an honorary second-generation survivor

For Leslie Sussan, a ‘New York Quaker Jew,’ telling her dad’s story is one way of trying to repair the world

Atomic bombing of Japan at Nagasaki, Aug. 9, 1945. Photo by Getty Images

Just as the children of Holocaust survivors are considered second-generation survivors, so, too, are the offspring of the hibakusha, Japan’s atomic bomb survivors. Leslie Sussan is considered one of them. She is the daughter of the late Herbert Sussan, who led a military film crew that documented the aftermath of the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Her father, who became a successful TV producer after the war, died of lymphoma in 1985. He attributed his fatal cancer to radiation exposure in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

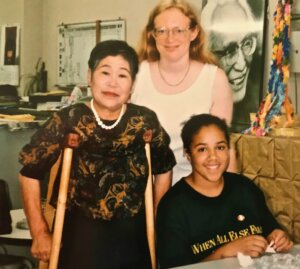

Leslie Sussan was first called a hibakusha by Suzuko Numata, who was a young woman when her leg was amputated after the bombing of Hiroshima. Sussan’s father filmed her in March 1946 and the daughter met her more than 40 years later when she visited Hiroshima.

Sussan, now 70, is a retired U.S. Justice Department lawyer and administrative judge who refers to herself as “a loudmouth New York Quaker Jew.”

Her father, she said, was like other hibakusha and survivors of the Shoah who, for many years, “simply could not bear to speak about the unspeakable events of the past.”

‘Being Quaker hasn’t made me any less Jewish’

Leslie Sussan grew up in Manhattan but has spent much of her adult life on the outskirts of Washington, D.C., where she’s been a longtime member of the Bethesda, Maryland, Friends Meeting. Her path to becoming a Quaker began when she attended Bryn Mawr, a women’s college with Quaker roots outside Philadelphia. She wanted to become a Jew at the age of 12 after learning that, because her mother was not Jewish, she was not considered a Jew. Her desire to convert to Judaism was thwarted by her Jewish father, who she said had held “a grudge against God” ever since his own father died right before his bar mitzvah.

“I don’t think he ever forgave God for that,” she told me.

“Being Quaker hasn’t made me any less Jewish,” she said. “Ever since I was a young teen, basically, my attitude toward being Jewish has been that I will never argue with a Jew who says I’m not Jewish and I will never deny to a goy that I’m Jewish.”

One of the things that drew her to Quakerism is that it reminded her of the Jewish notion of tikkun olam, that Jews are here to heal the world. The Quaker testimonies, a central part of the faith, include the goal of bringing “wholeness to communities wounded by violence and oppression.”

Spreading his story

Herbert Sussan was born in Brooklyn, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants. His family included a number of men who fled when Stalin started drafting Jews into the Soviet army. One of his aunts died in prison after being arrested for smuggling. He said she was imprisoned for being Jewish.

As a teenager, Sussan found work delivering radio scripts for a couple of agoraphobic writers and graduated from Stuyvesant High School. He started a pre-med course at New York University before he transferred to the University of Southern California, which was the only college in the U.S. at the time that offered a major in cinematography. His daughter said he told her that he got into USC under a Jewish quota. Among the lecturers at the university were Cecil B. DeMille and David Selznick.

During World War II, he served in the First Motion Picture Unit of the Air Force, where his immediate superior was a lieutenant named Ronald Reagan. The unit was based in Culver City, California, at the Hal Roach Studios, which came to be known as “The Laugh Factory to the World.” Laurel and Hardy and the Our Gang films were shot there. After the war, Amos ’n’ Andy, The Life of Riley and The Abbott and Costello Show were filmed at the studio.

During the war, Sussan spent time in the Philippines and then a small island near Okinawa. He was on the neighboring island when the bombs were used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He was then sent to mainland Japan, where he directed filming for the U.S. military’s Strategic Bombing Survey. In addition to documenting the devastation in the two Japanese cities, his crew filmed the results of U.S. firebombing in 20 other Japanese cities.

After the war, he had a long and successful career in television, but died in 1985 at the age of 64. His dying wish was that his ashes be spread in Hiroshima. Leslie Sussan learned that wasn’t possible under Japanese law, but she went to Hiroshima anyway with her 4-year-old daughter Kendra in 1987. They wound up spending a year there. Arriving in Hiroshima on Aug. 5, 1987, the day before the anniversary of the bombing, they attended the memorial ceremony the following day. In her memoir, Choosing Life: My Father’s Journey in Film from Hollywood to Hiroshima, she wrote that “suddenly, I choke and find myself in tears. This ceremony seems more like my father’s funeral than his own did. And I feel freer to mourn him here.”

Japanese media treated her like a celebrity, just like it did with her father when he visited in 1983. Early in her stay she arranged a memorial service for her father at the monument to hibakusha at Ground Zero.

“It came to me in the midst of the services that if I couldn’t spread his ashes that what I could do was spread the story of what had happened there and how it affected him,” Sussan said.

‘I just could not accept the inhumanity of it’

What happened in Hiroshima — and Nagasaki three days later — had never happened before and hasn’t happened since. Sussan, a 25-year-old second lieutenant, and his film crew went by train to Nagasaki first, where as many as 70,000 people perished. They arrived in early 1946, several months after the bombing. The crew of 11 had requisitioned all of the color film in the Pacific Theater. Theirs was the only color footage shot of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Black-and-white footage shot by Japanese film crews was confiscated by the American occupation force.

In a 1983 interview included in the Oral History Archives at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Sussan recalled that when the train carrying the film crew rolled into Nagasaki, he saw “the most astounding and horrifying sight I’ve ever seen.

“All of us were absolutely stunned,” he said, “and nobody could believe it was one bomb.”

The film crew was shocked that the bomb’s heat burned steel and blistered stone. In the 38 days Sussan spent gathering footage, he was so haunted by the human tragedy that he went to see an Air Force doctor about depression.

“I just could not accept the inhumanity of it,” he said in the oral history. Remarking on what he witnessed in a Nagasaki hospital coping with the survivors, Sussan said “such sites were never before seen by men. I knew at once that I would never be able to forget them.”

Most of the military personnel stationed in Japan for the American occupation were far less compassionate toward the civilian victims. The memory of Pearl Harbor and the huge American casualties suffered in the Pacific Theater were still fresh in their minds. But Sussan was startled by the absence of visible antagonism toward the Americans by Japanese civilians.

“Why did he see the suffering and human pain where most of his compatriots saw only well-earned victory?” his daughter asked in her memoir.

A third of the footage that Sussan and another American military film crew shot for the Strategic Bombing Survey focused on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, according to the author and documentary producer Greg Mitchell, who has covered the nuclear beat for some 40 years and has seen all of the Sussan footage. It amounts to around 15 hours, Mitchell said. Most of the film was shot without sound.

The film was promptly classified as top secret and withheld from the American public. During his career in TV and film, Sussan made several attempts in the 1950s and ’60s to get access to the footage, appealing personally to then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, NBC News anchor Chet Huntley, CBS legend Edward R. Murrow and former president Harry S. Truman, all of whom he had contact with in his capacity as a producer at NBC, CBS and Screen Gems.

None of his efforts were fruitful. He wanted to use the footage shot in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to make a documentary that would warn the world about the horror of nuclear war, and his failure to do so overshadowed for him all his TV accomplishments, which included producing the popular NBC TV series Wide, Wide World on NBC in the late 1950s. When Herbet Sussan died in 1985, his daughter said, he was an angry and bitter man.

It’s unclear when exactly the film his crew shot was declassified and moved to the National Archives. In 1978, Sussan met a Japanese publishing executive at a New York photography exhibit where pictures from Japan of the atomic victims were displayed and told him about the film. As a result, a grassroots campaign in Japan raised $500,000 to purchase all of the footage. In 1982 at a U.N. Special Session on Disarmament, Sussan saw two Japanese films made with it. An American-made documentary, Dark Circle, was released that same year.

Sussan wondered what impact the footage might’ve had if it had been seen by the American public right after the war, whether it would’ve had any effect on nuclear proliferation.

“I felt that if this story was told and seen by people in the United States and people throughout the world, they would realize that this sort of nuclear weapon has no place with man on earth,” he told reporter Susan Jaffe in an interview for a story that appeared in the March 1983 issue of Nuclear Times, a now-defunct magazine devoted to nuclear disarmament.

Kaddish for her father

Leslie Sussan has been back to Hiroshima six times since her initial visit in 1987. In October she’ll go back to the city, where as many as 140,000 died as a result of the atomic bomb. Hiroshima, she said, feels like home to her.

Every August, a Japanese religious ritual known as obon takes place in which the spirits of deceased people are said to visit their families. In Hiroshima, the families write messages on lanterns that small boats carry away on a river so that the spirits can go back back to the other side. Throngs of atomic bomb victims are believed to be visiting their living relatives, haunting their beloved city.

One year, Leslie Sussan and her daughter Kendra participated in the ritual, which involves writing something on the lanterns before they are set on the water. The child wrote Pempah, the name she used for her grandfather, on her lantern. On another lantern, her mother wrote, “May we thirst for peace as they thirsted here for water.” It was a reference to hibukusha who were desperate for water due to the terrible heat from the blast. The notion of writing messages to the deceased in Japan is reminiscent of a certain Hasidic sect in Crown Heights whose rebbe once brought messages from his Hasidim to the gravesite of the previous rebbe in Queens to read to departed relatives in the world to come.

Leslie Sussan, self-proclaimed “loudmouth New York Quaker Jew,” said her story about her father and the trauma he suffered as a result of filming the hibakusha in Japan is part of the Japanese storytelling tradition of kataribe, which in Hiroshima is focused on the horrific atomic attacks.

“This is my kataribe,” she wrote in her memoir. “This is my kaddish for my father.”