How William Friedkin, a Jewish kid from Chicago, made us fear the Catholic devil

The director of ‘The Exorcist’ and ‘French Connection’ is dead at 87

William Friedkin directed chilling meditations on human (and demonic) evil. Photo by Sylvain Lefevre/Getty Images

William Friedkin, the Jewish hand behind one of the most famous film explorations of Christian evil, The Exorcist, has died at the age of 87.

Born in Chicago on August 29, 1935 to Jewish refugees from Ukraine, Friedkin was raised in an observant, kosher home. Speaking to the Jewish Journal in 2012, the director said “I’m a Jew, and that’s it. In my heart I believe completely in the Ten Commandments, but I also believe we are all imperfect and at times we just can’t cut it.”

Human imperfection was a major theme of Friedkin’s work, which was decidedly eclectic.

Friedkin began his career in the 1960s as a TV director and documentarian. His first narrative film, 1967’s Good Times, was a vehicle for Sonny and Cher. He followed it up with another musical comedy, The Night They Raided Minsky’s and an adaptation of Harold Pinter’s bleak “comedy of menace” The Birthday Party in 1968.

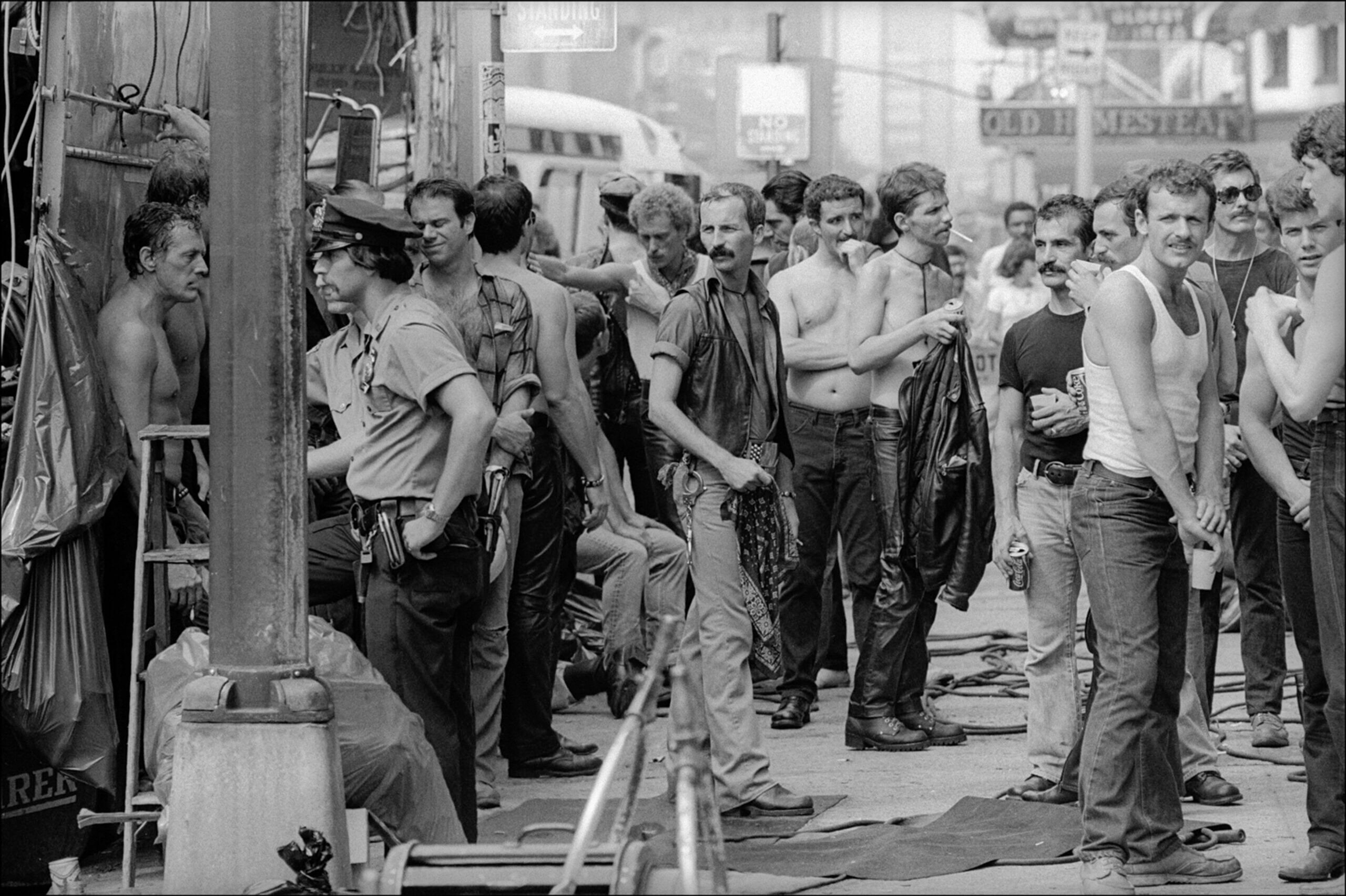

Friedkin was prolific and celebrated throughout the ’70s, beginning the decade with another play adaptation, of Matt Crowley’s The Boys in the Band, a milestone for its time for its nuanced portrait of gay friends in New York City. (He’d return to documenting gay life in a more controversial fashion in 1980’s crime film Cruising, which was protested even during its production by gay rights activists for depicting gay men as deviants and murderers. Friedkin defended the film, stating that its content wasn’t meant to be seen as representative of the community and it has since been reevaluated.)

In 1972, Friedkin won best picture and director at the Academy Awards for The French Connection, about a New York detective uncovering a heroin-smuggling syndicate. Its story was informed by Friedkin’s time filming the 1966 documentary The Thin Blue Line, about the police force. The film was lauded as much for its performances and gritty realism as its car chase.

Friedkin often managed to take the trappings of genre and elevate them to what critics regarded as art. 1973’s The Exorcist, about a girl possessed by an ancient demon, and the young and old priest working to save her soul. He came to the material through William Peter Blatty’s novel.

“I wasn’t Catholic so I had no idea what the hell an exorcism was,” Friedkin said earlier this year, at a Turner Classic Movies event for the film’s 50th anniversary, nonetheless, the idea “turned out to have some legs.”

This was an understatement. The Exorcist, with an Academy Award-winning screenplay by Blatty, was the first horror film nominated for the Oscar for best picture and spawned a still-thriving sub-genre of Catholic-themed terror. A new chapter in the franchise, The Exorcist: Believer, featuring original cast member Ellen Burstyn, is slated for release in the fall. Friedkin was not enamored of his film’s original sequel, 1977’s Exorcist II: The Heretic, directed by John Boorman, once calling it “the worst piece of sh— I’ve ever seen.”

Following The Excorcist’s success, he made 1977’s Sorcerer, which he believed to be his best film and perhaps his most jarring confrontation with evil. (Often cited as a remake of the film Wages of Fear, Friedkin maintained it was merely based on the same source material, a novel by “confirmed antisemite” Georges Arnaud, who Friedkin said hated the film for shooting a sequence in Jerusalem.)

When asked how his Jewishness influenced his films, Friedkin was loath to make the connection. Indeed, in several interviews in recent years, Friedkin stated that he “believed in the teachings of Jesus” and, on an episode of Marc Maron’s WTF podcast, spoke of his wonder at seeing the Shroud of Turin, on which is said to be the face of Jesus.

Known for his quick and often caustic wit in interviews, to say nothing of his creative profanity, Friedkin told the Forward‘s A.J. Goldmann in 2016 that he didn’t try to reconcile his directorial brooding with his personal humor.

“I think I’d rather take life with a sense of humor, but I’m more interested in drama that’s dark or that’s about the eternal struggle of good and evil,” Friedkin said. “Those make the best dramas. But personally I have to take things lightly. You’d go absolutely crazy if you didn’t.”

Friedkin continued making films until close to his death. His last announced feature, The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, based on the Pulitzer-winning novel and play by Jewish writer Herman Wouk, is set to debut at Venice next month. If the film is at all like the novel or play, it will be about what drives men to either blindly follow orders or to reject a rigid and unethical hierarchy. That theme recalls a horror film Friedkin never got to make.

When Goldmann asked Friedkin if he was ever interested in making a movie about the Holocaust, Friedkin said it was hard to do something different with the material, but then considered what he could add to it.

“If I were able to do anything about that it would be about the Germans and the madness that overtook a sophisticated, intelligent population.” Friedkin said. “To me, it was demonic possession on a massive scale.”