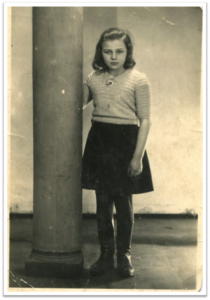

She survived the Holocaust in Lublin and became a scholar and symbol of Jewish resilience and resistance

Nechama Tec’s history of Jewish partisans in Belarus inspired the 2008 film ‘Defiance’

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The American Jewish sociologist Nechama Tec, who died Aug. 3 at age 92, saw European Jewish survival in the tragic 20th century as a matter of exceptionalism.

Author of a 1993 history about Jewish partisans in Belarus that was adapted for the 2008 Hollywood film Defiance starring Daniel Craig and Liev Schreiber, Tec herself belonged to one of the few Polish families which survived the Nazi era in situ. Only three Jewish families from her hometown of Lublin, from a prewar population of around 40,000, survived the Holocaust intact.

Tec’s 1986 book When Light Pierced the Darkness examined how a modest minority of Polish Catholics also altruistically sheltered Jews, often despite personal feelings of antisemitism inculcated in them during their upbringing. As a sociologist, Tec suggested that Poles who rescued Jews did so because of an atypical societal identity as outsiders, combined with a track record of helping the downtrodden and a personal sense of independence.

A relatively minuscule, albeit heartening, group, these Poles who were unusually benevolent to Jews were not negligible, Tec argued. She cited the Polish resistance fighter Jan Karski, who claimed it was “counterproductive” to focus only on the murderous majority. Instead, Tec suggested, the “extreme goodness” shown by altruistic Christians who saved Jewish lives may “serve as a model for others to imitate their paths now and in the future.”

This essentially optimistic view was nuanced with a perhaps surprisingly wry wit, which was especially pertinent to Tec’s writings on wartime rebellions insofar as she noted the French historian Henri Michel’s dictum that European resistance movements during World War II “started with gestures of malicious humor.”

Yet drollery was impossible when, during the Nazi era, as she observed in 1997, Jews were “defined as less than human” and “targeted for total biological extinction.” And the Germans “excelled in inventing the most diabolical tortures, varying in degree of subtlety.”

She decisively dismissed comments that somehow Jews passively accepted victimhood as participants in their tragic fate. Instead, Tec asserted that Jewish people “engaged in open armed resistance” more often than other oppressed groups.

Indeed, Jewish resistance militias expressed “moral boldness,” or what might be summed up as chutzpah. This virtue complemented those Jews who, without joining paramilitary groups, maintained traditional observance, even in ghettos, as a form of “unarmed humane resistance.”

In 2004’s Resilience and Courage, in which she conducts a comparative study of woman and men in the Holocaust, Tec described the macho milieu of resistance fighting, with a few Jewish women accepted mainly as objects of romantic interest, while in ghettos and concentration camps, Jewish women typically showed more psychological fortitude than their male counterparts.

Why? Some researchers posited that since the male role of breadwinner was removed from Jewish men during racist banning from society, they were at a loss. Whereas however tough the circumstances, Jewish women instinctively carried on with their traditional role of trying to keep the family alive.

Whether from a feminist or gender studies viewpoint, Tec ardently defended such overlooked participants in the anti-Nazi struggle as Masha Bruskina. A Belarusian Jewish nurse and resistance martyr, Bruskina was hanged at age 17 by the German Wehrmacht for helping Red Army soldiers to escape Nazi-occupied Byelorussia.

Depicted in a harrowing series of photos of her execution alongside two non-Jewish fellow resistance fighters who were subsequently honored by their compatriots, Bruskina remained anonymous despite abundant evidence identifying her. The refusal by Russian historians to admit that a 17-year-old Jewish woman was capable of heroic actions, Tec suggested, might be due to antisemitism.

Fortitude and singularity were also themes in Tec’s biography of Oswald Rufeisen, a Polish Jew who survived the Nazi occupation by hiding in a convent of the Sisters of the Resurrection, converting to Christianity while saving the lives of hundreds of Jews and Christians.

Although Tec’s religious adherence was likewise disguised as Catholic during wartime, she felt no impulse to imitate the precedent of Rufeisen, who after the hostilities ceased, joined the Carmelite Order and eventually became a Catholic priest.

After some early publications on sociological topics like gambling and drug abuse, for nearly a half century, Tec was fully absorbed with understanding rescue and resistance in the context of the Holocaust.

And so in a 2018 post on the website of the Union for Reform Judaism, Tec openly scorned a claim in Bruno Bettelheim’s The Informed Heart that Anne Frank’s family could, and should, have armed themselves before hiding in the Secret Annex in Amsterdam. That way, Bettelheim implied, when the Nazis arrived to arrest them, the Franks could have ended in a blaze of glory akin to the gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

Tec’s response to this revenge fantasy was to comment drily: “Clearly Bettelheim did not understand the insurmountable obstacles Jews faced under Nazi domination in the 1940s.”

Instead of such retribution, Tec followed the precedent of Jan Karski by looking at how the oppression of the Jews led to Gemilut Hasadim (the giving of loving kindness). Her 2013 book Resistance looks at how Jewish resistance might be redefined to allude not just to armed resistance, but also benevolent actions, survival strategies, and retaining personal humanity when faced by evil.

So despite the grievous subject matter she dealt with for much of her career, Nechama Tec’s books are ultimately a heartening message to Jewish readers of the present and future.