How American Jews have managed to survive a history of antisemitism and bigoted fanaticism

‘Acts of Faith,’ an exhibit at the New York Historical Society, explores the history of religion and prejudice in America

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

“How did religion become a vital and contested part of American life?” That is the key question posed at the entrance to the New York Historical Society’s absorbing exhibition Acts of Faith: Religion and the American West.

Amid the roiling religious prejudices that beset our country — and our world — today, few queries are more worthy of exploration, and the exhibit provides a history lesson par excellence in how the past set the table for our present. Focusing on America’s westward expansion over the course of the 19th century, the exhibit introduces us, gallery by gallery, to the spiritual lives and traditions practiced by cohorts of religious communities as diverse as our society today.

We meet members of many different Native peoples; visit the missions of varying Protestant and Catholic ministries; follow Mormon settlers as they seek community; observe the travails of African Americans both before and after the Civil War; bear witness to the arrival of Jewish and Chinese immigrants. And along the way, we absorb with increasing horror the hard truth that religious discrimination, prejudice and conflict, sometimes violent, were always present in our country, from the moment the first Christian colonists came ashore.

These, too, the exhibition makes clear, were “acts of faith,” falling into the same category of intolerant behaviors and hate crimes we see today. Then, as now, their underlying message is also the same: to assert who “belongs” and who does not.

For the European settlers of the 17th and 18th centuries, the “other” was personified by the first Americans, the indigenous tribes who had inhabited the continent and had created and practiced their own spiritual traditions. But even when Native tribe members were persuaded to convert to Christianity, missionaries and white settlers often still considered them “pagan.”

The newcomer Christian settlers then rationalized as further “acts of faith” the dispossession of non-believers from the lands they had long inhabited.

It was a double steal, declared the Seneca leader Sagoyewatha (1758-1830), also known as Red Jacket, seen in the exhibit in a moodily atmospheric portrait. He had defended his people’s traditional spiritual practices and accused the Christian missionaries, stating “You have got our country but are not satisfied; you want to force your religion upon us.”

Nonetheless, Native Americans’ rights to remain on their land — and practice the belief systems they had developed there — were increasingly nullified. Their marginalization is vividly portrayed in Seneca painter Ernest Smith’s ironically titled painting Progress. It depicts an isolated group of Native Americans looking down from a western bluff on territory that had once belonged to them; now, a steamer chugs down the river, passing newly built settlers’ log cabins.

We also learn from a wall text that, shortly after the Erie Canal opened in 1825, connecting the east to the Great Lakes, New York Governor DeWitt Clinton had declared, “Before the passing away of the present generation, not a single Iroquois will be seen in this State.”

Nor were Mormons, members of the Church of Latter Day Saints, exempt from threats of violence as they threaded their way westward from upstate New York, the place of their first community, in search of a safe place to practice their beliefs. Indeed, in 1838, Missouri’s governor issued an “extermination order” against them, we learn from illustrated magazine reports.

By the 1870s, Chinese immigrants had also become targets of a “Chinese Must Go” political movement. They weren’t the only ones. An 1881 political cartoon on display from the San Francisco magazine The Wasp captures the increasing political attacks on any group perceived to not fit in with their religious beliefs. Witness the depiction of the maternal “Columbia,” and her “Three Troublesome Children,” represented as disruptive Chinese, Mormons and Native Americans.

Nor could missionaries and representatives of various Christian and Catholic groups seem to agree on which religion should become America’s dominant faith. Instead, they battled each other in competing speeches and newspapers and they sought dominance in “saving” and converting communities to their respective faiths. And — who knew? — much like today, 19th-century public and private schools fought over the legality of Bible readings and prayers in school.

And where were the Jews in all this? In its presentation of new Jewish immigrants to America, rather than focus on antisemitism, the exhibit highlights the country’s promise of religious freedom, as codified in the Constitution’s First Amendment. Here, unlike in many European countries, Jews were not excluded from freedom of movement or from government service. Thus we read about Joseph Jonas (1792-1869), the first permanent Jewish settler west of the Allegheny Mountains, the founder of Cincinnati’s B’nai Israel Congregation in 1824 and a member of the Ohio legislature.

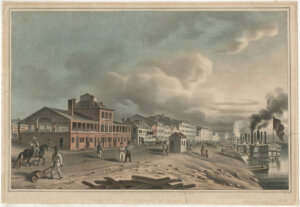

The Jewish community’s resilience is also on display — literally, in a dollhouse-sized diorama of what’s labeled as St. Louis’ first Rosh Hashanah service, which took place in 1836 in a rented room above Max’s grocery store, located by the busy river port. (Take a peek inside and you’ll see the shofar being blown.) By 1840, the Jewish community there had grown sufficiently to organize and fund a Jewish cemetery and burial society, and in 1841 establish the United Hebrew Congregation, the first Jewish congregation west of the Mississippi — and which still remains a vital and active synagogue today.

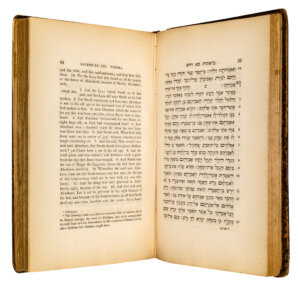

Just as relevant to the endurance of the Jewish American community are the objects in the vitrine right beside the diorama, including an original copy from 1845 of the first Hebrew-English edition of the Five Books of Moses to be published in the United States. The publisher and English-language translator was the German-born American immigrant Rabbi Isaac Leeser (1806-1868), who undertook the project (and his subsequent translation of the Tanakh) to make sure that the People of the Book in this country had copies of the most important books in the Jewish canon.

And then there is Rabbi Leeser’s 1850 article from The Occident and American Jewish Advocate, the very first Jewish-American periodical in English, titled “The United States Not a Christian State.”

Because I had come to the exhibit wondering what it might teach us about religious tolerance in the face of the ongoing rise in antisemitic and white nationalist acts, I read his words with particular interest. “It is foolish to pretend to assert that there is a state religion; either that it is Judaism, Christianity, or anything else. All men have an equal right to be here,” he wrote.

And yet, he continues, “Might makes right here as well as elsewhere; and the fanatics for all opinions know this perfectly well, and they therefore endeavor to make their views those of the majority, that they may carry them through and force them on the community by the brute power of numbers.”

The dilemma has not changed, I thought. Nor has the most important act of faith for all Americans: to believe in our democracy.