There’s more to Madonna’s Jewish story than just Kabbalah and social media posts about Israel

The pop star was exposed to Judaism from an early age and studied with a choreographer whose work was infused with Jewish themes

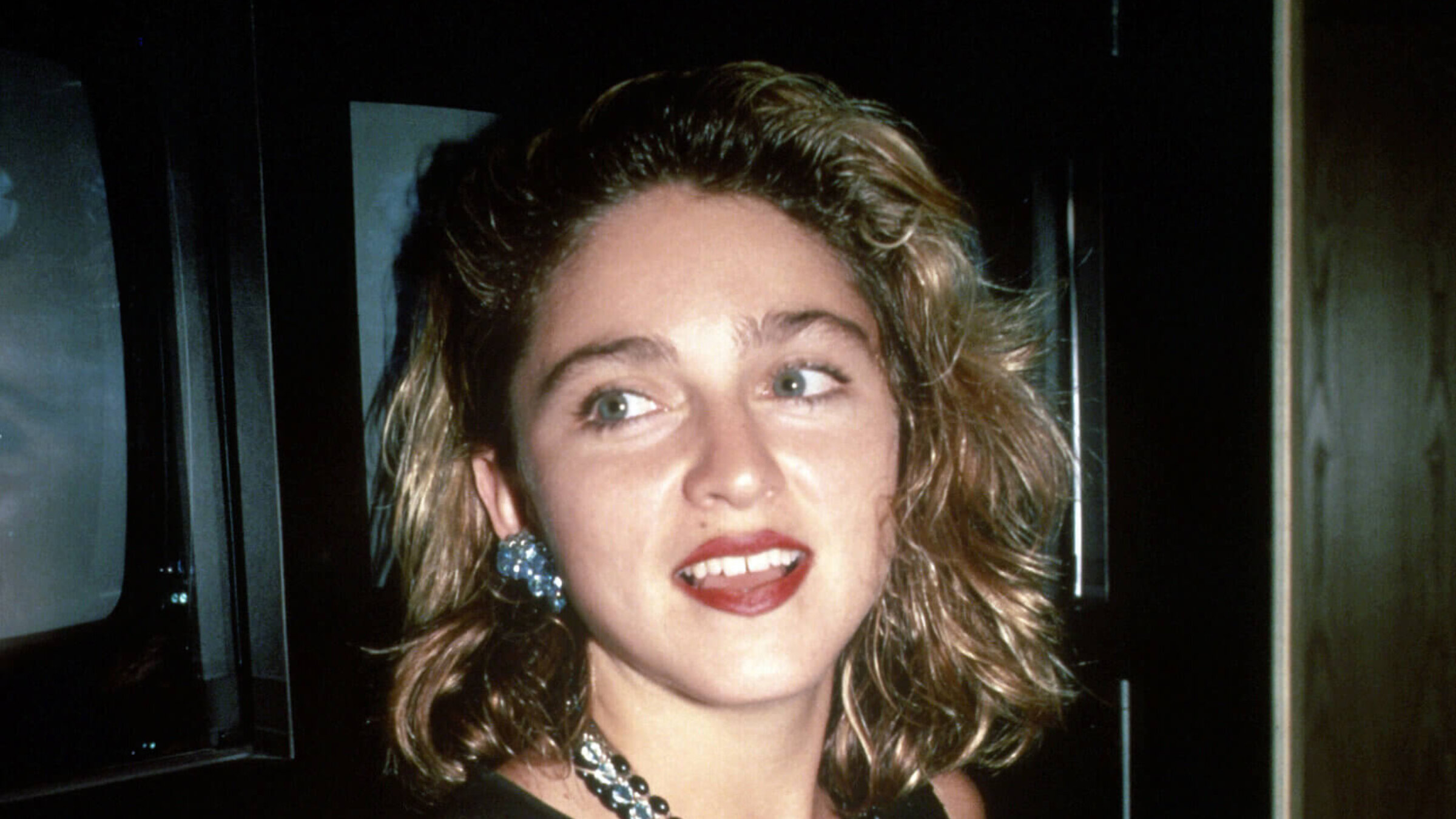

Madonna, circa 1985. Photo by Getty Images

Within a day of the Hamas terrorist attacks in Israel on Oct. 7, international pop-star Madonna took to Instagram to share her reaction to the slaughter of Israeli civilians with her 19 million followers. Her post included video clips of the terrorists rampaging through Israeli towns and villages, and her accompanying commentary said, “What is happening in Israel is devastating. Watching all of these families and especially children being herded, assaulted and murdered in the streets is heartbreaking.

“My heart goes out to Israel. To families and homes that have been destroyed. To children who are lost,” she continued. “I’m praying for you.”

She concluded her message with three Israeli flag emojis and a call “for peace. For the world.”

To the casual follower or fan of Madonna, this heartfelt outpouring of sympathy with Israel might have come as a surprise. But to those who have been paying closer attention to the pop superstar over the years, this gesture was totally in character with Madonna’s longstanding support of Israel and her strong connection to Judaism and the Jewish people.

This is made especially clear in the new 858-page critically acclaimed biography, Madonna: A Rebel Life, by Mary Gabriel, who recounts in great detail Madonna’s religious upbringing and her deep and abiding lifelong spiritual searching that culminated with her decades-long involvement with the controversial Los Angeles-based Kabbalah Centre.

Madonna’s parents raised their children in a devout Roman Catholic household; Madonna attended several Catholic elementary schools. Her mother died when she was only five years old, leaving her father, Tony Ciccone, fully in charge of their schooling and upbringing. In Pontiac, Michigan, religion was “fundamental to life,” writes Gabriel, “and because the population was so diverse, the congregations were, too… A street might have a Catholic church on one corner and a synagogue on the other.”

According to Madonna’s brother, Christopher Ciccone, their father made a “very deliberate effort to introduce his children to cultures outside their own so they would not be ‘prejudiced’ or ‘unnerved by different people.’” The Ciccones belonged to a Catholic-Jewish organization through which they learned about Jewish holidays and ritual. “I celebrated Passover all my life, without realizing it was Passover. I thought it was Easter,” said Christopher.

In high school, Madonna’s dream was not to be a singer and a pop star but a dancer. At 19 years old, in 1978, before settling in New York City to pursue those dreams, Madonna attended a six-week intensive summer program in modern dance sponsored by the American Dance Festival in Durham, N.C. It was there that she first met Pearl Lang, renowned as the first dancer who Martha Graham allowed to perform some of her own roles, and eventually recognized as Graham’s greatest interpreter.

Lang went on to form her own company, and her dances were infused with references to Jewish plays, poetry, and legends. “Most of her dances explored Jewish themes,” Gabriel writes. “Many of them derived from Yiddish literature, which she expressed with an emotional range that ran the gamut from abject despair to religious ecstasy…. Lang described the essence of her work as the search for God. The intellectuality, spirituality, and passion of Lang’s dances, not to mention the rigor of the work, all appealed to young Madonna.”

As most people know, Madonna’s first husband was actor Sean Penn. The two got hitched in 1985, but within two years, their tempestuous relationship came to an end, and they were divorced in 1989. What many people do not know is that Penn’s father, Leo Penn, was a blacklisted actor who came from a family of Russian and Lithuanian Jewish immigrants.

Madonna gave birth to her first child, daughter Lourdes, in 1996. The baby’s father was Carlos Leon, Madonna’s fitness trainer. Motherhood steered Madonna back to thinking about her own religious upbringing and how she wanted to raise Lourdes.

“Religious beliefs had long been part of her self-education,” Gabriel writes. “She studied the Gnostics and early Christians, Buddhism, and Hinduism. She told an Italian journalist, ‘Although I am Catholic in my bones, I am looking for something else in my blood.’”

Madonna discussed her dilemma with film producer Susan Becker, who mentioned that she was attending classes taught by a rabbi about the Jewish mystical tradition called Kabbalah. Until the mid-20th century, Kabbalah was an esoteric discipline reserved for study by married Jewish men over the age of 40 who were already well-versed in all aspects of Torah. But an excommunicated rabbi named Philip Berg began teaching a version of this ancient Jewish wisdom tradition to all comers in Los Angeles.

Berg’s teachings required no previous knowledge of Judaism or Hebrew. Berg attracted a following that read like an A-list of Hollywood celebrities, including Demi Moore, Ariana Grande, Britney Spears, Diane Keaton, Roseanne Barr, Sandra Bernhard, and most notably and ardently, Madonna. She began attending classes at the Kabbalah Centre, where she found what she was looking for: “She believed Kabbalah was exactly what she needed to help prepare for her new role as mother,” writes Gabriel.

Putting aside for the moment the question of just what was being taught at the Kabbalah Centre, and if it had any relationship at all to the Jewish mystical tradition as explored in the Zohar, or the Book of Splendor, thus began a long-term relationship between Madonna and the Centre, which extended to supporting her philanthropic and charitable works, especially her devotion to building children’s hospitals and schools in Malawi, through her organization Raising Malawi.

Soon after her studies began, mystical themes started finding their way into her songs, beginning with her 1998 album, “Ray of Light.” Madonna once said of her pre-Kabbalah self, “What was I thinking before I was thinking?” she said. “I don’t miss being an idiot.”

Madonna’s 2000 song, “Isaac,” from her album, Confessions on a Dance Floor, prominently features Yemeni-Jewish singer Yitzhak Sinwani, who taught at the Kabbalah Centres in Los Angeles and London. Singing in a Yemeni Hebrew dialect, Sinwani recorded “Im Nin’alu,” a popular Yemenite Jewish song whose lyrics say that if doors on earth are closed, the gates of heaven remain open.

Madonna took bits of Sinwani’s track and constructed the song “Isaac” around his part, with appropriate lyrics to match, including “open up my heart, and cause my lips to speak” – a phrase from Jewish liturgy adopted from Psalm 51. Her original lyrics also expressed a Kabbalah-informed view of Judaism: “The gates of Heaven are always open / And there’s this God in the sky and the angels / How they sit, you know, in front of the Light / And that’s what it’s about.” It wasn’t exactly Gershom Scholem, but it did evince a basic understanding of her subject matter.

Gabriel writes, “The Madonna who wrote ‘American Life,’ who had political and social statements to make, did so through the lens of Kabbalah. It taught, she said, that ‘the only thing that matters in life is your relations with people … The philosophy is, if you really stripped [it] down, … love your neighbor as yourself.’ She said it also taught that ‘nothing is what it seems, and the more tinsel there is on something, the less real it is.’”

“Madonna tried to structure her life around Kabbalah’s teachings,” Gabriel continues. “If a change in her attitude wasn’t always evident, the outward trappings of her belief were on display. She wore a red string on her wrist to ward off evil. She drank pricey Kabbalah water. ‘It’s from Canada and certain kinds of prayers by highly enlightened persons affect the molecular structure of the water’,” she told one journalist.

When her 2000 tour arrived in Berlin, Madonna took a side trip with friends Stella McCartney, Ingrid Casares, and Gwyneth Paltrow to visit the Sachsenhausen Nazi concentration camp. According to the German newspaper Bild Zeitung, at the site Madonna “did not say anything, she prayed.”

Not for the first time and not for the last, Madonna courted controversy with her video for the title track to the 2002 James Bond film, Die Another Day. While she had previously been condemned by elements within the Catholic Church for the sacrilegious use of Christian iconography, this time, some in the Jewish community took offense at her use of Jewish symbols. Madonna sports a tattoo on her upper arm of the Hebrew letters lamed, aleph, and vav. As if that were not enough to score demerits – Jews are forbidden to have tattoos, period, and spelling out one of the names of God in Hebrew letters on a tattoo just made it all that much more offensive – she is also seen wrapping tefillin, traditionally regarded as the sole province of Jewish men, and definitely not an acceptable use of the leather straps by a non-Jew, especially in the context of the video.

In 2003, Madonna began writing children’s books “because the ones she read her children were without ‘moral messages’,” writes Gabriel. “Madonna told her stories using Kabbalah as her guide. The first, ‘The English Roses,’ … was about five 11-year-old girls based loosely on [her daughter] Lourdes and her British friends at school. The lessons they learned were about jealousy and envy. Proceeds from the book’s publication went to Spirituality for Kids, a Kabbalah Centre program that tried to provide children with the spiritual tools they need in life.” The book knocked J.K. Rowling’s fifth Harry Potter installment out of the number-one spot on UK hardcover fiction bestseller lists.

Madonna filmed a documentary for her 2004 “Re-Invention” world tour called I’m Going to Tell You a Secret. The film, which includes much discussion of her Kabbalistic beliefs, culminates with a visit to Israel, where she visited the graves of several Jewish sages in northern Israel as well as Rachel’s Tomb near Bethlehem.

By 2004, Madonna had been studying Kabbalah for seven years. At this point, writes Gabriel, “Madonna had taken the Hebrew name Esther after the ‘courtesan who became queen’ and saved the ancient Jewish people from annihilation. It wasn’t a name she used but one she adopted for the same reason a Catholic chooses a confirmation name – to identify her ‘metaphysical’ self.”

Madonna finally settled into her new identity. Gabriel quotes her as saying, “It took me a long time before I could go from the girl sitting in the back of the class wowed by all the information, keeping notes, to thinking, there is a point to this life, now I know why there’s chaos and suffering and pain in the world, and I can actually do something about it.”

Around the same time, Madonna urged all her close friends and family members to attend classes at the Kabbalah Centre. She even enticed her reluctant brother, Christopher. “She thought it would be helpful, and in many ways it was,” Gabriel quotes him as saying. “I did get a number of things that were useful to me, but as an institution I just can’t be part of it.” Madonna’s loyal yet independently savvy brother felt the environment the Bergs cultivated at the Centre seemed antithetical to Kabbalah’s teachings. “It was all celebrities,” he said. The studies amounted to “breaking down your ego in a room full of egotists.”

By 2006, the Kabbalah Centre was under scrutiny for the apparent disconnect between its beliefs and practices. These included sales of “Kabbalah water,” with “centuries of wisdom in every drop,” a type of “blessed, restoring” face cream, and copies of the Zohar sold for eight times the price of what one typically cost in a religious bookshop. By 2011, Madonna was decoupling her philanthropic efforts, including Raising Malawi, from their entanglement with the Kabbalah Centre, which by then was being investigated by both the IRS and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York.

But even after the pillars of the Kabbalah Centre came crashing down, Madonna’s beliefs did not falter. She would often return to Israel, to visit and to perform. And on her 2012 tour, she “had tiny Zohars taped to mechanisms” that transported performers, including Madonna herself, underneath the stage. “I’m so superstitious,” she explained, “and I don’t trust stages.”

That 2012 tour, the MDNA tour, opened on May 31 in Tel Aviv. At the time, tensions between Tehran and Jerusalem were running hot, and there were fears of a regional war breaking out. Some on Madonna’s team questioned whether she should cancel the Israeli concert. Madonna refused. “I said we’re going, we’re going,” she said “The threat of war’s not keeping me out of a country. Actually, it’s an invitation.” And when she performed in France a few weeks later, she again courted controversy, this time by flashing an image of National Front leader and presidential candidate Marine Le Pen with a swastika superimposed on her forehead in a video accompanying her song “Nobody Knows Me.”

In 2019, the Eurovision Song Contest was held in Tel Aviv, following the Israeli singer Netta’s 2018 victory. Amid protests, Madonna went ahead with her plans to perform at the 2019 contest. “Madonna’s relationship with Israel was long and deep – through Kabbalah, through her many visits to the country, and through her associations with its leaders,” writes Gabriel. “What was less recognized was her involvement with Palestinians. Madonna’s Ray of Light Foundation supported projects in the West Bank and Gaza and paid teachers’ salaries at UN-funded schools in Gaza after the Trump White House cut funding.”

At the end of the Tel Aviv concert, a man and a woman climbed the stairs arm in arm, their backs to the audience. “One displayed a Palestinian flag, the other an Israeli flag. The silhouettes of a mosque, a synagogue, and a church appeared, followed by the words WAKE UP.”

Madonna performs at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., Dec. 13-14 and December 16, and at Madison Square Garden in New York City on January 22-23 and January 29, 2024.