In the Warsaw ghetto, where disease, cold weather and violence all exerted heavy tolls

Lauren Grodstein’s ‘We Must Not Think of Ourselves’ focuses on glimmers of hope amid overwhelming catastrophe

In 1943, a Nazi soldier checks someone’s ID in the Warsaw Ghetto. Photo by Getty Images

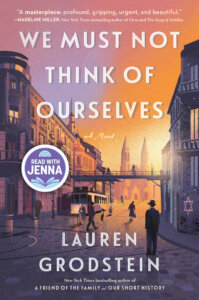

We Must Not Think of Ourselves

By Lauren Grodstein

Algonquin, 304 pages, $29

As the Holocaust recedes in time, the complexities and varieties of Jewish resistance are moving into sharper focus. Rebellion, we now realize, wasn’t limited to taking up arms, committing sabotage, or eluding capture; it could mean countering the Nazi ideology of death with an affirmation of life.

Music was one powerful prong of resistance. At New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage, the recent National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene revue, Amid Falling Walls, celebrated a trove of tunes culled from the ghettos, camps and forests. New or repurposed, these songs satirized the oppressors, mourned the dead, and buoyed the survivors.

Other contemporary chroniclers looked to posterity. The Jewish ghettos of Eastern Europe — most famously Warsaw, but also Lodz, Bialystok and others — launched ambitious archival projects, collecting newspapers and posters, diaries, drawings, photographs and more. “May history attest for us,” Warsaw’s Dawid Graber wrote in August 1942.

Graber’s words turn up in the epigraph of Lauren Grodstein’s bittersweet Warsaw Ghetto novel, We Must Not Think of Ourselves. Grodstein, whose great-grandparents fled Warsaw two decades before World War II, was inspired by the city’s Jewish archivists, whose work was buried and later partially recovered.

Given its sources, Grodstein’s novel wasn’t quite what I was expecting: a panoramic, if fictionalized, overview of ghetto life, told from multiple perspectives, and culminating in the dramatic, doomed 1943 Warsaw Ghetto uprising. It is instead a more modest, if still eloquent, enterprise, focused on the experiences of its narrator, Adam Paskow, a secular middle-aged widower and English teacher. It’s a love story, or two, and also a philosophical tale about moral choice in extreme circumstances.

As the novel opens, Paskow is recruited to the ghetto’s archival project, codenamed Oneg Shabbat (“the joy of the Sabbath”), by its leader, Emanuel Ringelblum, a character based on the actual Polish Jewish historian. “Our task is to pay attention,” Ringelblum says.

Buttressed by a sense of community and mission, a small stipend and extra food, Paskow dutifully interviews a handful of acquaintances about their lives. His subjects are drawn from two overlapping groups: students taking his (literally) underground English class and the nine people with whom he shares a cramped ghetto apartment.

Those testimonies are shoe-horned into the mostly chronological narrative, expanding its reach. At times, the story also circles gracefully back to Paskow’s recollections of his happy marriage to Kasia Duda, a Polish gentile and English-language translator. The match never thrilled her family. But after her accidental death, her distraught father, Henryk, leans on Paskow for comfort. When the Nazis invade Poland in September 1939, Paskow’s father-in-law becomes a source of both harassment and hope.

Forced into the overcrowded ghetto with the rest of Warsaw’s Jewish population, Paskow, with a wheelbarrow in lieu of a moving van, leaves even his precious photo albums behind. He takes with him only memories, a few essentials, and valuable contraband jewelry that may help him survive.

In the ghetto, starvation, disease and unpredictable spasms of Nazi violence are looming, if unequally distributed, threats. Initially at least, those who still have resources can feast, while others beg for crumbs. The increasingly dire circumstances upend, or at least challenge, conventional morality. Smuggling fuels the ghetto economy; forgery and other forms of deceit save lives.

Szifra Joseph, Paskow’s beautiful star student, injects additional complexity. “Just because we’re the so-called victims here doesn’t mean we have the individual moral high ground,” she says. “What I mean is you can also be a bad person in a bad position.” Joseph will make some questionable choices of her own to buy her orphaned brothers a chance at survival.

Paskow is a fine teacher who beguiles his students with English-language poetry and distributes his change to beggars. But he, too, transgresses. He falls into an affair with a married woman, Sala Wiskoff, who lives in their shared apartment along with her husband, Emil, and two sons.

Emil, if he knows of the adultery, doesn’t bother to object. A counselor to the Judenrat, the ghetto administration charged with drawing up the deportation lists, he has more pressing concerns. In any case, he, too, is a denizen of what Paskow calls “this strange underwater world where there were no more rules about right and wrong.”

Grodstein makes clear the precariousness of ghetto life, as starvation, frigid temperatures and typhus exact heavy tolls, and the mere promise of bread and jam lures thousands to trains destined for Treblinka. But she dwells less on Warsaw’s miseries than on glimmers of humanity amid the catastrophe.

Her characters are perennially hungry, but they sometimes savor unexpected treats: dried apricots, chicken soup, sausages and freshly baked bread. They recite poetry and comfort themselves with dreams of an imminent Allied victory and a better future. Enveloped by hatred, and facing death, they remain — at least some of them — capable of love and sacrifice.

It is hard in the ghetto, harder even than elsewhere, to know when a friend might turn into a foe. Or whether an ambivalent ally, receptive to bribes, might provide an exit route. Betrayal seems not only possible, but likely.

One character, the former head librarian at the University of Warsaw, disdainfully calls the ghetto Jews “a hollow people who prefer to think of themselves as mere victims instead of moral actors like everyone else.” Will Paskow, a flawed but sympathetic soul, eventually prove him wrong?

Despite its grim setting, We Must Not Think of Ourselves won’t repel or depress readers. The greater risk is that Grodstein’s skillful, warm-hearted storytelling will short-circuit their sleep.