Finally, her quest for restitution from Germany succeeded — but at what psychological cost?

In ‘Summons to Berlin,’ Joanne Intrator recounts a grueling journey to receive compensation

Nazi officials march through the streets of Berlin, 1944. Photo by Getty Images

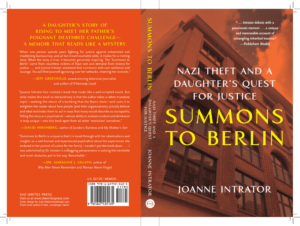

Summons to Berlin: Nazi Theft and a Daughter’s Quest for Justice

By Joanne Intrator

She Writes Press, 273 pages, $18

In her memoir’s prologue, Joanne Intrator recalls her father’s dying words. Gerhard Intrator, a German Jewish refugee, asked her: “Are you tough enough yet? Do you know who you are?” Summons to Berlin records her attempts to find the answers.

A New York psychiatrist deeply marked by her parents’, and Germany’s, turbulent history, Intrator initially wasn’t certain what her father meant. She ultimately decided he was asking her to continue his efforts to receive compensation for 16 Wallstrasse, a commercial building in Berlin’s Mitte section that was owned by the family and looted by the Nazi regime.

Intrator took to the task with both trepidation and gusto. As she writes, it consumed many years, required numerous trips to Berlin, and would “very nearly break me.” Launched in 1993, her quest makes for an instructive and engrossing story, marred by some repetition and digressions, but for the most part adeptly told.

“The Holocaust was not simply murder,” Intrator writes. “It was also a humiliation, and a systematic attempt to despoil an entire people of everything they owned and held dear.”

Before leaving Berlin, Intrator’s once-prosperous family lost property, businesses and livelihoods. Her father, who had completed his legal training, was unable to practice law in either Germany or, later, the United States. Her mother, also a German Jewish refugee, had hoped to become a doctor. Frustrated and angry, she gave little support to her daughter’s own medical ambitions. Intrator herself has been subject to lifelong “free-floating anxiety,” the product, she suggests, of inherited trauma.

There were other tragedies. Intrator’s paternal grandfather, Jakob, left Germany with his wife in 1941, and died just hours after reuniting with his son in New York. A cousin, Max Karp, perished in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, and other cousins also were murdered in the Holocaust. The building at 16 Wallstrasse would come to represent for Intrator what she calls “all that unforgivable, embittering loss.”

After World War II, East Germany, where the building was located, did not entertain restitution claims. German reunification in 1990 made restitution possible, but not easy. Only over time, spurred by generational change, would Germany move towards a fuller acknowledgment of Nazi crimes and a more expansive understanding of what was known as Wiedergutmachung, or reparations.

Fragments of Intrator’s story were familiar to me from social media and a 2017 exhibition, Stolen Heart: The Theft of Jewish Property in Berlin’s Historic City Center, 1933-1945, at the Leo Baeck Institute at the Center for Jewish History in New York. (That show was adapted from a more comprehensive 2013 Berlin exhibition.) I knew that Intrator’s fight, fueled by her determination and fluency in German, involved peeling back layers of history; it seemed, in the end, triumphant.

Summons to Berlin emphasizes the steep costs exacted on Intrator’s psyche and, eventually, her marriage. The details of the split from her now-deceased spouse remain vague, with Intrator, who has a son, erring on the side of discretion.

In other respects, though, she is precise and candid, particularly in excoriating the family’s German lawyers. Jost von Trott zu Solz — related to Adam von Trott zu Solz, executed for his role in the failed July 1944 assassination plot against Hitler — was “physically imposing yet disconcertingly aloof,” she writes.

He actually represented Intrator’s Berglas cousins, the building’s co-owners. Her family’s lawyer, Dorothea Von Hülsen, seemed disinclined to tangle with von Trott, whose firm employed her husband. Both attorneys were retained by a Zurich-based company, Sonex, funded by a wealthy Holocaust survivor, which would receive 15% of the proceeds from any settlement. The lawyers’ incentives and loyalties were murky at best.

One sticking point was Intrator’s understandable reluctance to share restitution with heirs of the Heim & Gerkin Furniture Company, which had “Aryanized” the property under Nazi law in the first place. Since the building had been nationalized by the East German government in 1972, a Heim heir, Johanna Weber, had also filed a restitution claim.

To make matters worse, German law and bureaucracy appeared to place the burden of proof on the dispossessed Jews. Largely disregarding history, the bureaucrats demanded extensive documentation and suggested that Intrator’s paternal grandfather could have lost the property because of bad business decisions.

In this infuriating legal quagmire, Intrator writes, “I felt compromised and stuck, dependent on professionals I could not trust.”

Finally, she wisely sought outside help, enlisting the prominent attorney Hans J. Frank, himself a refugee from Hitler’s Germany, as a paid consultant. She took an immersion course to improve her German and hired a private investigator to dig into the building’s history.

Intrator already knew that the textile factory there had been used in the manufacture of Nazi flags. The investigator found that the manufacturers, Berliner Fahnenfabrik Geitel & Company, used Russian slave labor — and also mass-produced the stigmatizing yellow Stars of David that Jews in Germany and elsewhere were forced to wear. Unsurprisingly, the owners and managers of both Heim & Gerkin and Geitel were all Nazi Party members.

Apart from being a dedicated daughter intent on justice, Intrator, as a psychiatrist, has a serious claim to fame: She has teamed with the celebrated psychologist Robert D. Hare on brain imaging studies of psychopaths. Hare, the author of Without Conscience and creator of a widely used diagnostic checklist for psychopathy, provides the memoir’s foreword, describing their joint research.

The issue of psychopathy has obvious relevance to the Nazi era. “Fantasies of the Gestapo and Nazis had caused my childhood terrors and were driving my professional research on psychopaths,” Intrator writes. But her attempts to weave psychiatric discourse into the narrative are more often distracting than illuminating. While psychopathy might be a useful diagnosis for some of Hitler’s henchmen, it doesn’t do much to explain the legal morass in which Intrator found herself.

Far more striking is this statistic, from the Stolen Heart exhibition: Of the many expropriated Jewish property owners in Berlin’s Mitte, only 5% of them (or their descendants) have received restitution. After fighting what her advocate Hans Frank calls “this maddening battle with a horrible, immutable past,” and making a gut-wrenching concession, Intrator manages to be among them.