‘Israeled,’ a new Urban Dictionary word, becomes proxy battleground in Middle East conflict

Users have contributed several entries for a new verb — ‘Israeled’ — since Oct. 7

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The user-run internet lexicon Urban Dictionary emerged in the early 2000s to define and occasionally create online slang — and, in doing so, has both shaped and reflected the internet, as well as indexing it.

And as dozens of one-sided entries for a new verb, “Israeled,” have appeared on Urban Dictionary after Hamas’ Oct. 7 attacks — and that tens of thousands of users have battled to get the entries down-voted or deleted — the site has become an important staging ground for contests over who should control the online narrative of the war.

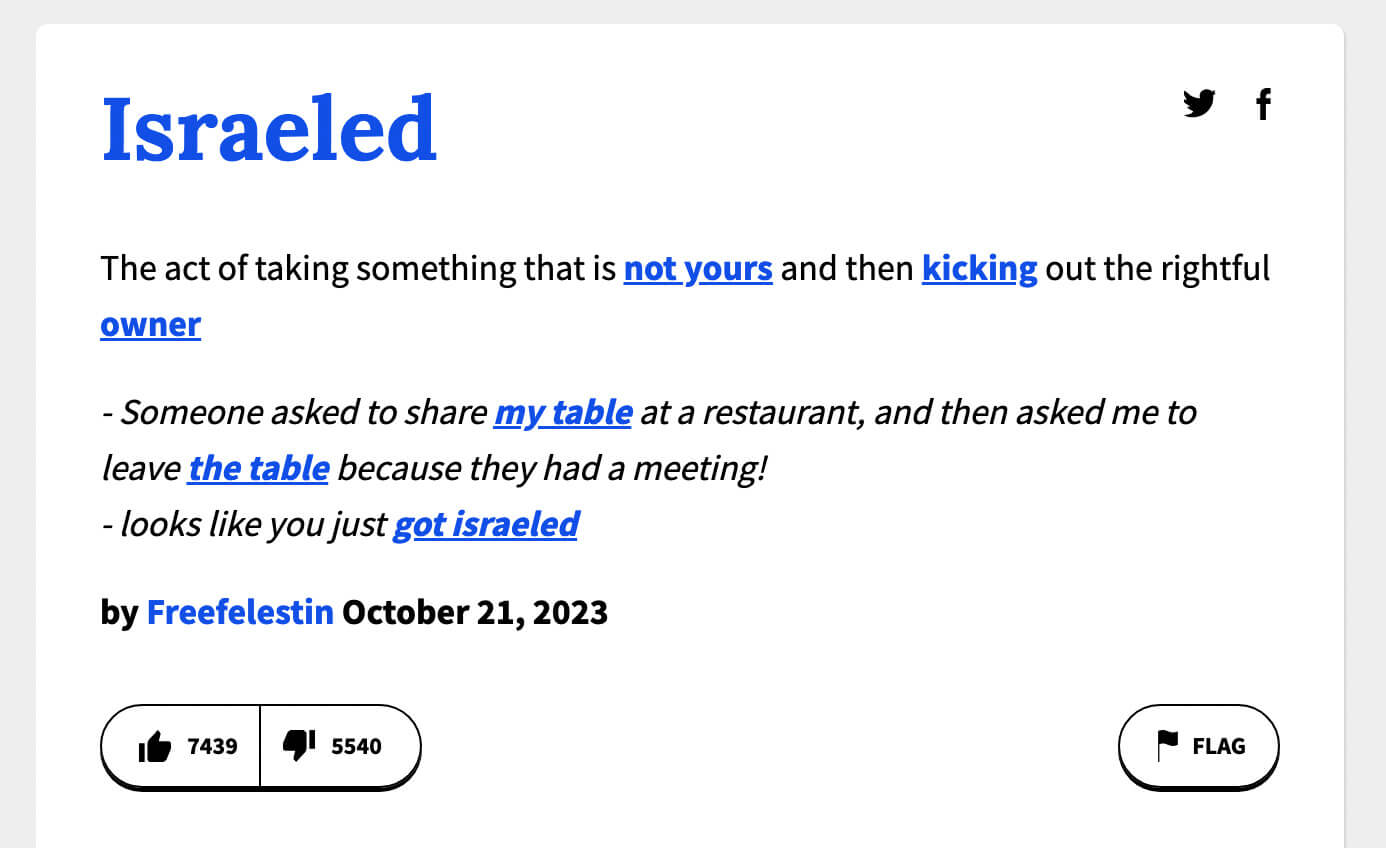

The 30-plus entries for “Israeled” so far submitted to Urban Dictionary more or less share a definition. One, posted Oct. 22, reads: “Verb. Use this term to refer to someone who steals something and acts like the victim.”

All Urban Dictionary entries use the word in a sentence for clarification, with many proceeding along these lines: “In a restaurant, someone asked to share my table. I agreed. After a moment, he asked me to leave because he has a meeting! I’ve been Israeled.”

The top-ranked entry had racked up more than 9,000 upvotes and 17,000 downvotes as of Dec. 29.

Only one of the entries — buried on the second page of definitions for “Israeled”— seems to take a pro-Israel tack: “When the entire world completely ignores historical facts, and justifies terrorist acts against you.” That, too, received more thumbs down than thumbs up.

Anyone with a Facebook or Gmail account can add a new definition to Urban Dictionary, and every submission is reviewed by volunteer editors before publication, according to the website’s help page. According to a 2013 article in The New York Times, only five people need to approve a new word for it to be added.

So while an advisory to down-vote and report definitions of “Israeled” to Urban Dictionary moderators circulated in some Jewish WhatsApp groups this week, the coordinated effort seems unlikely to have an effect. Urban Dictionary has a reputation for crassness and irreverence — its popularity since its founding in 1999 largely derived from its definitions of baroque sex terms and swear words — and “Israeled” hardly defies that. (One of the site’s homepage-featured words on Friday was “centaur ass.”)

Moreover, Urban Dictionary — one of the top 500 most-visited websites in the United States — has been scrutinized over the spread of racism and misogyny on the platform in recent years. The second-ranked definition of “girl” was, at one point, “The creation of satan. Designed to destroy the existence of mankind.”

Definitions can be flagged for removal, but the content moderation team that reviews the reports generally seems to take a laissez-faire approach. And a cursory review of the site’s terms of service does not find any clear-cut violations in “Israeled.” Though definitions that provide “information that is false, misleading or inaccurate,” are deemed unacceptable, the site reserves the right to not take down even definitions that are in violation.

Those offended by the entries might take heart in the knowledge that few people are going to Urban Dictionary to learn about the Israel-Palestinian conflict. But beneath that is a more troubling reality: that this is just what the internet looks like, now, and the picture it paints of Israel isn’t pretty.