Why a Jewish artist thinks his exhibit’s cancellation is evidence of censorship and antisemitism

Phillip Schwartz was ready to exhibit his Holocaust-related artwork. An arts center wanted to address accusations of genocide in Gaza.

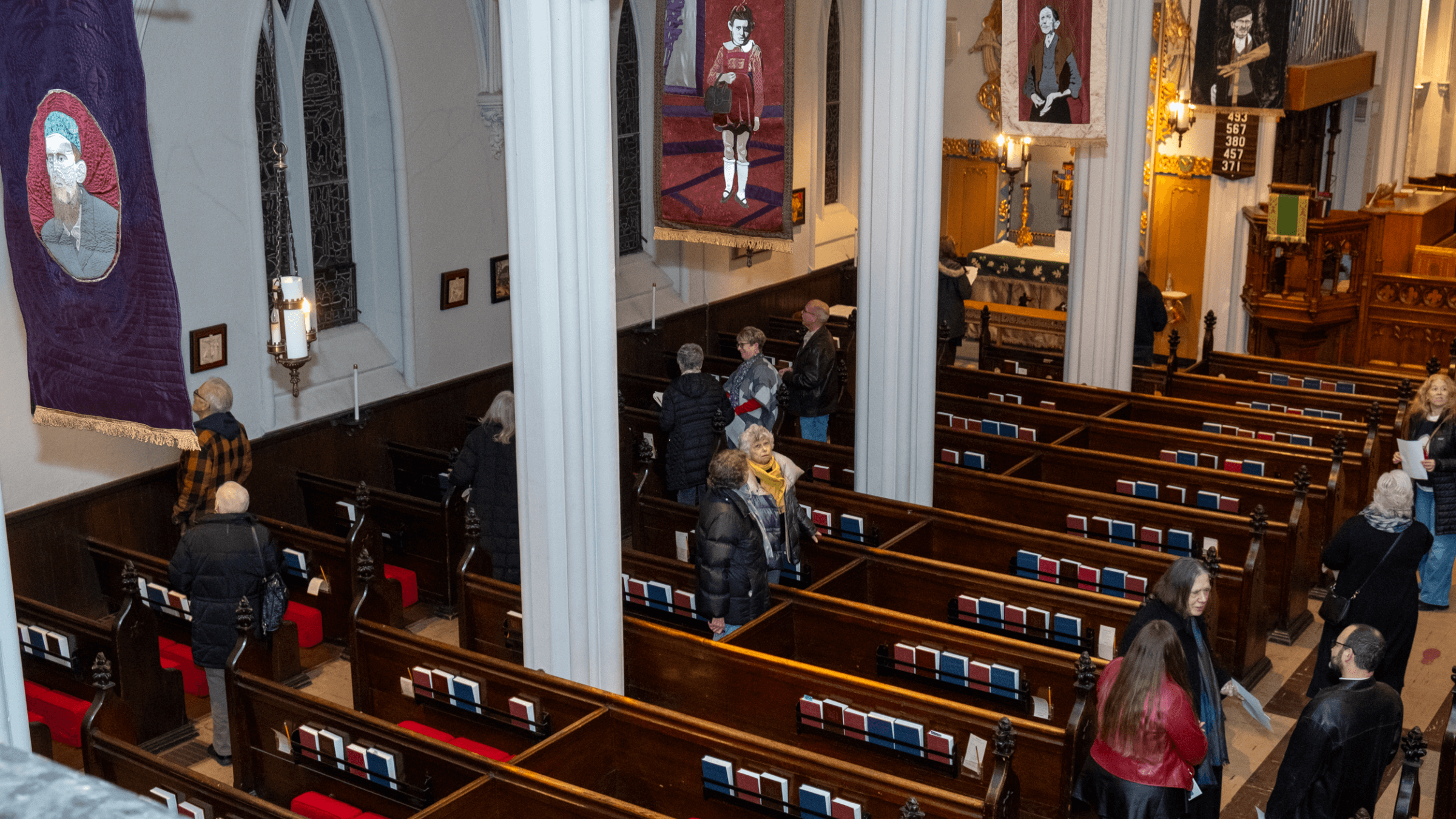

Banners by Phillip Schwartz at Christ Church. Photo by Michael Del Rossi

HUDSON, NEW YORK — Last Saturday evening, on the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, which the United Nations designated in 2005 as International Holocaust Remembrance Day, art lovers gathered at Christ Church Episcopal for the opening of Shoah: A Meditation on The Holocaust, a new exhibition of Holocaust-themed artworks by Phillip Schwartz, who lives in this riverfront town about two hours north of New York City.

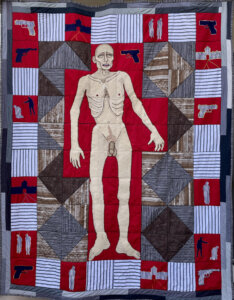

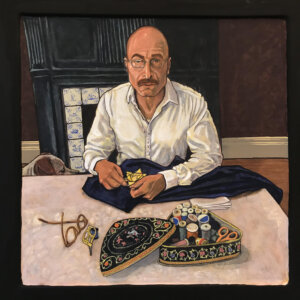

The church sanctuary, where Schwartz’s artworks were displayed, was full of well-wishers and the merely curious. The setting of this sacred space lent an appropriate serenity and solemnity to Schwartz’s paintings, textiles and icons, some portraying highly stylized, sometimes gruesome images of Holocaust victims. Schwartz himself appears as the subject in several of the paintings; he is alternately seen sewing a yellow Star of David on a jacket, looking at the viewer from behind iron bars, and peering out at the viewer from inside a crematory. Schwartz’s execution of this thematic series, which he has been working on for five years, is simultaneously a triumph of formalism and a rare case of creating beautiful images that express humanity at its most degraded.

But for the artist, the opening of the exhibition was a somewhat bittersweet occasion. As of just over a month ago, the exhibit at the church, which is located on a residential side street, was planned as an auxiliary branch of a larger exhibition, whose main installation was slated for the more high-profile Hudson Hall, a multidisciplinary arts center on Warren Street, Hudson’s main drag, which presents nationally known artists and performers alongside regional and local artists. A show at Hudson Hall pretty much guarantees a hefty and repeated turnout from the institution’s loyal following, as well as greater media attention than the hanging of art in a non-traditional space such as Christ Church, which has no tradition of mounting art exhibitions in its elegant sanctuary.

Planning for Schwartz’s exhibit at Hudson Hall began in March 2023, after a team from Hudson Hall paid a visit to Schwartz’s home studio to view his artwork.

“We were just blown away,” Hudson Hall executive director Tambra Dillon told me. “[Phillip] works across different mediums, and his work is really powerful, but it’s also really beautiful. No matter what medium he’s working in, it’s meticulously executed, and we really liked him, and we really liked the artwork.”

As is typical practice at Hudson Hall, Dillon asked Schwartz if he could recommend an artist whose work would pair well with his. Schwartz put Hudson Hall in touch with his fellow artist Ifé Franklin. The two friends attended art school together in the 1980s and were collaborating on a proposal for a mural addition to the Horwitz-Wasserman Holocaust Memorial Plaza in Philadelphia. Just as Schwartz’s work addresses in highly personal fashion the not-so-distant history of his ancestral relatives, several dozen of whom were murdered by Germans and local collaborators in what was then Romania, Franklin’s artwork, according to her website, “infuses multiple art practices to honor the lives, histories, cultures, and traditions of African people throughout the diaspora with a concentration on the formerly enslaved of North America.”

To add some intellectual ballast to the exhibition, Hudson Hall recruited Daniel Mendelsohn to give a talk at the opening. Mendelsohn – who lives about 25 minutes down the road from Hudson near Bard College, where he teaches — is a prolific contributor to The New Yorker and is the author of 10 books, including the internationally best-selling and award-winning Holocaust family memoir The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million.

Planning for the installation proceeded slowly over the course of the rest of 2023. The centerpiece of Schwartz’s work for the show would be several monumental, 9-by-12-foot quilts, which were to be hung aloft from lighting rigging in Hudson Hall’s upstairs performance space. Other works of his would be on view in the hall’s first-floor gallery spaces, adjacent to a gallery featuring Franklin’s work.

As Schwartz continued to produce additional images, more than could be displayed at Hudson Hall, he arranged with the leaders of Christ Church to install a parallel exhibition consisting of paintings, icons and banners that would hang aloft over the church’s pews. Schwartz had attended a Stations of the Cross liturgy at the church, which inspired his work both thematically and formally.

“I struggled at first with trying to fit the story of the Holocaust into the story of the Passion, but I soon realized that it was impossible to distill a twelve-year-long mechanized genocide into a small group of paintings,” he wrote in his exhibition statement.

Then, in mid-December, just six weeks before the exhibition was set to open, Schwartz was informed by Hudson Hall about a change in direction in how they wanted to present his work.

“Given the current Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it would be inappropriate to not include both Jewish and Muslim perspectives,” Dillon wrote in an email to Schwartz.

Schwartz says he was baffled and frustrated by this pivot to recontextualize the exhibition of his Holocaust-related work in relation to current events in the Middle East.

“I am not a surrogate for the State of Israel, nor do I think that adding a Palestinian/Muslim voice is appropriate to this particular body of work which refers to the Holocaust, a catastrophic event that took place at a time before the State of Israel existed, and to my personal history and to homophobia,” he wrote in an email to Dillon.

Schwartz says that there was talk of adding ancillary programming, such as adding the work of a Palestinian artist to the exhibition or replacing Daniel Mendelsohn with a Palestinian speaker.

“I’m just thinking,” said Schwartz, “what the hell is this going to look like? What are they going to talk about? Clearly, they’re not going to talk about my work. I mean, like, what connection is there? I was really confused what a Palestinian scholar had to do with my work, or the Holocaust or, you know, anything that had to do with the show. I said, ‘You realize I am not Netanyahu. I’m not a proxy for Netanyahu or for the State of Israel. And my work has nothing to do with any of that.’”

For her part, Dillon defended Hudson Hall’s pivot, saying that both Schwartz’s and Franklin’s work address “genocides.”

“To me, Israel and the Holocaust can’t be separated,” she said. “Phillip was very explicit in his work. It deals with genocide, oppression, persecution, and those were in the headlines of every major news outlet in the world. There was absolutely persecution, and the Palestinian side was declaring it a genocide. The show dealt directly with genocide that was a major topic of conversation and current affairs. We felt it was difficult to not somehow address that.”

Dillon added that not to address a current “genocide” taking place in Gaza would be “an act of willful blindness.”

“There is a pro-Palestinian community in Hudson,” she said. “And there was a need, when we’re talking about genocide, to find a way to address that. And our hope was to have art help, in the same way that Philip, being a Jewish person who identifies very strongly as being Jewish, had connected with a Christian church to bridge that divide. We thought this would be kind of another nice thing to do.”

Hudson is a diverse city, and that diversity includes a vocal segment who have used social media, graffiti, and projections on buildings to express their anti-Israel, pro-Palestinian sentiments. The fear that this anger might be turned against Hudson Hall over an exhibition about the Holocaust strikes Daniel Mendelsohn, among others, as craven and cowardly.

“It’s clearly idiotic,” Mendelsohn told me. “One understands why they’re doing this. But the proper context for talking about the Holocaust is the history of European Jewry and the history of Germany in the 1930s. That’s the only context, as far as I’m concerned, for talking about work related to the Holocaust. And this cockamamie business about needing to provide context — I think it’s extremely pernicious, really, partly because it suggests that there is some connection between the destruction of European Jews in the 1930s and ’40s and what’s going on now in Israel and Gaza. And the assumption behind that is pernicious. It would be risible if it weren’t so offensive.”

“It’s clearly a false equation,” Mendelsohn added. “To say that it is a false equivalent is not not to be able to deplore what is going on right now in Israel. But these are two totally different things. There is no equivalence between what is happening now, or you could even say between what Israel is doing to the Palestinians, and the destruction of European Jewry during the Second World War. It’s not equivalent in scale, it’s not equivalent in intent, it’s not equivalent in its means, its goals, its ideology — there is no equivalency here.”

“I want to stress,” said Mendelsohn, “that to say this is not to endorse what’s going on in Israel, is not not to be able to be horrified by many aspects of the Israeli response to Oct. 7. But these are two different things. It’s apples and oranges. I don’t see an equivalency there.”

In an email to Hudson Hall in December, Schwartz expressed similar concerns. “I have shown and worked with Palestinian artists in the past. During the Second Intifada, some of my work was included along with that of other Jewish and Palestinian artists from around the world. The show was both a call for peace and for Palestinian independence. The work was exhibited in Bethlehem and in Jerusalem. There should definitely be an exhibition at Hudson Hall representing the work of one or perhaps many Palestinian artists.

“But,” he added, “I find it ironic that in reaction to the fear of antisemitism and controversy, controversy in the community, Hudson Hall is treating me in a way that feels like a combination of antisemitism and censorship.”

Schwartz is not alone in having trepidations about recontextualizing the Holocaust in light of the Oct. 7 attacks.

Last Thursday, Jan. 25, Palestinian professor and peace activist Mohammed Dajani spoke at a virtual event organized by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in advance of International Holocaust Remembrance Day. In his remarks, Dajani said, “Expressing empathy and respect for the Holocaust victims is not only a tribute to the past, but also a way of diminishing racism, bigotry, prejudice and intolerance in the present and future. … As such, the Holocaust should not be politicized, linked to or compared with other genocides, nor should its commemoration be avoided due to violent political events or current wars.”

In the end, Schwartz felt that the recontextualization of his exhibition in the manner intended was untenable and a disservice to his work, and he withdrew his work from Hudson Hall, which then cancelled the exhibition. “I’d love for Hudson Hall to reach out more to Hudson’s Muslim community,” Schwartz wrote to Dillon, “but not as a way to do damage control for the decision to show the work of a Jew.

“Oddly enough,” he wrote, “although my work is apparently too Jewish to be shown at Hudson Hall, it is being welcomed warmly by the clergy and congregation of a beautiful historic Episcopal Church.”