After the war broke out, Sara Erenthal kept making art — in the name of peace

The artist’s new exhibition situates viewers in a big, diverse protest against the Israel-Hamas war

Sara Erenthal poses in front of one of her murals at her new exhibition at the Brooklyn Artery. Photo by Sam Lin-Sommer

“Perhaps later today,” Brooklyn-based artist Sara Erenthal texted me a couple of weeks ago in response to my request for an interview. “I’m not feeling so well after sitting five hours on Manhattan Bridge.”

The day before, on Sunday, she and an estimated 1,500 other protesters shut down the bridge to call for a cease-fire in the war between Israel and Hamas. Erenthal had helped make a banner with the words “Let Gaza Live” that organizers draped between the columns of the bridge’s entrance.

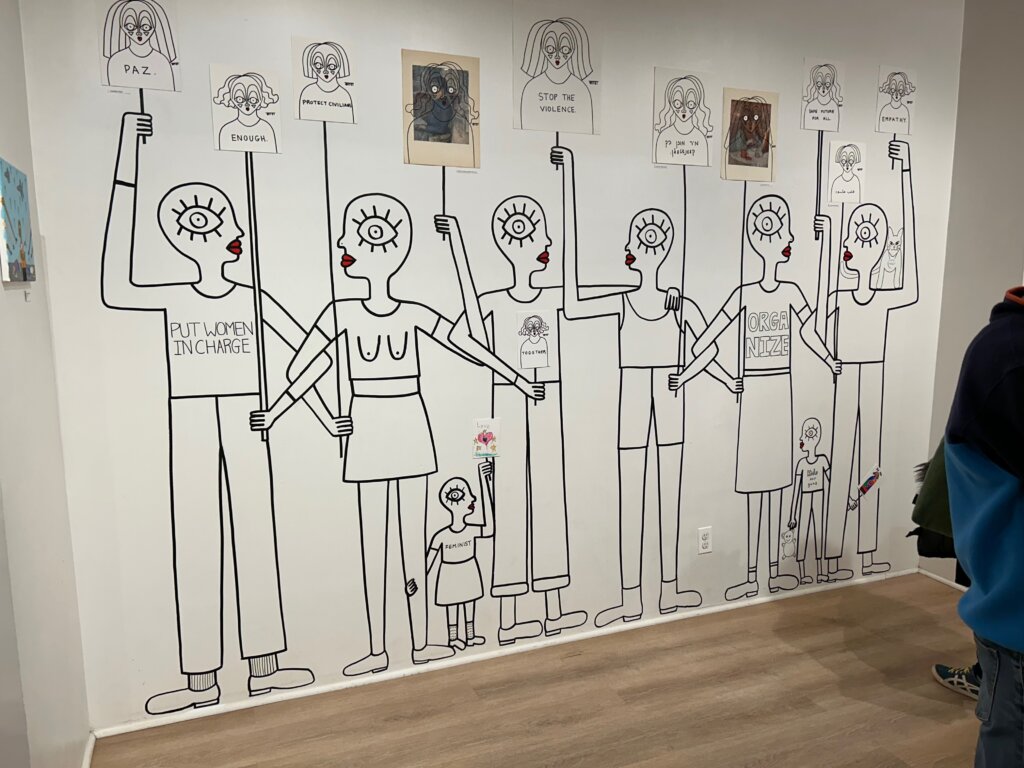

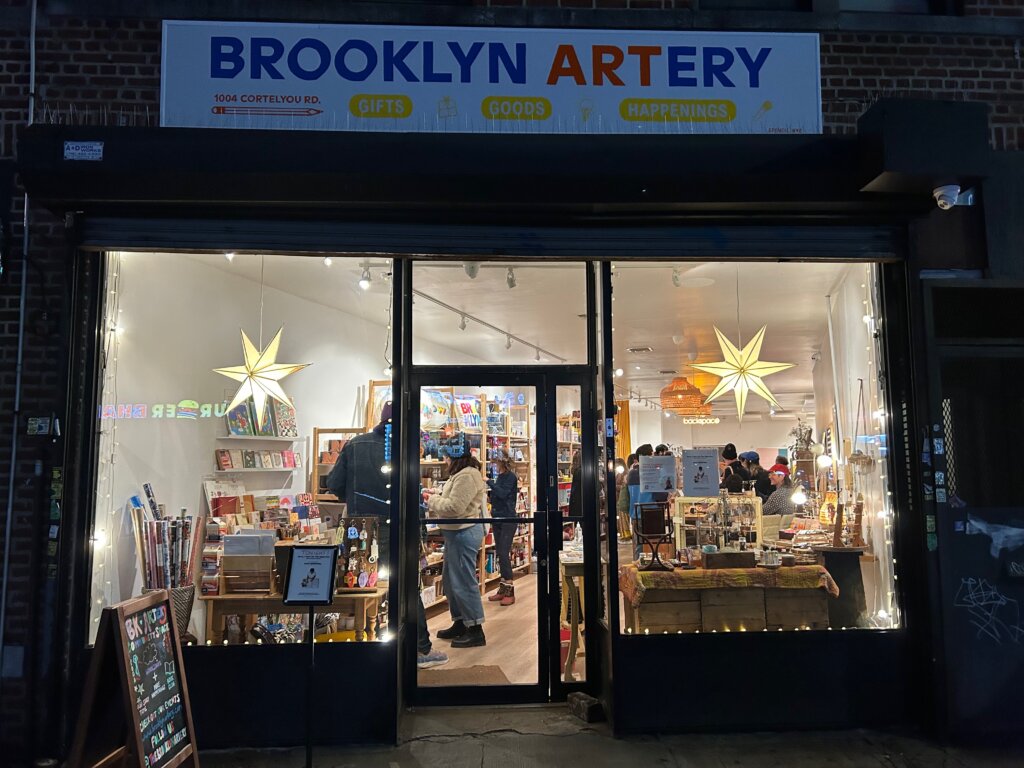

She then had to muster the energy to finish work on her appropriately titled exhibition, Sorry, I Can’t Do This Right Now (But I’m Doing it Anyway), which was set to premiere four days later at the Brooklyn Artery, a gift shop and community space in Flatbush. By opening night, she had pulled it off, painting two walls with murals of demonstrators, many of them linking arms, holding up signs of peace.

The title is pulled from a text message Erenthal sent to the store’s co-owner, Annie Del Hierro, while they were planning for the show’s opening. Erenthal had felt stretched thin as she processed news about Israel and Palestine, attended cease-fire protests, and worked on her art.

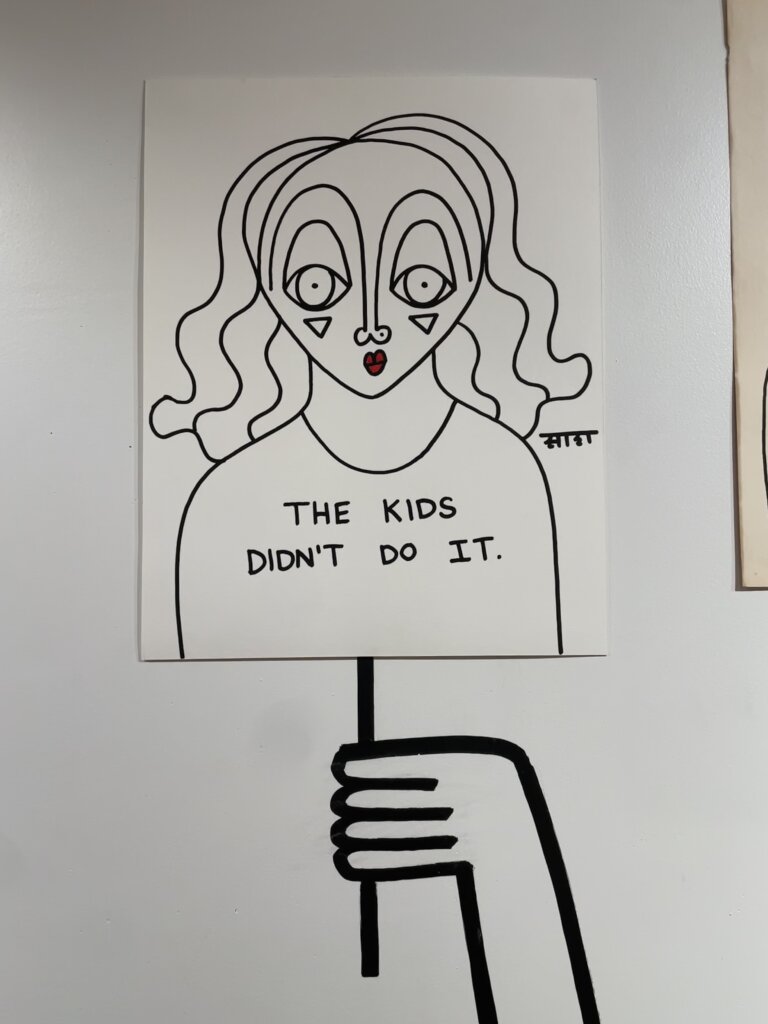

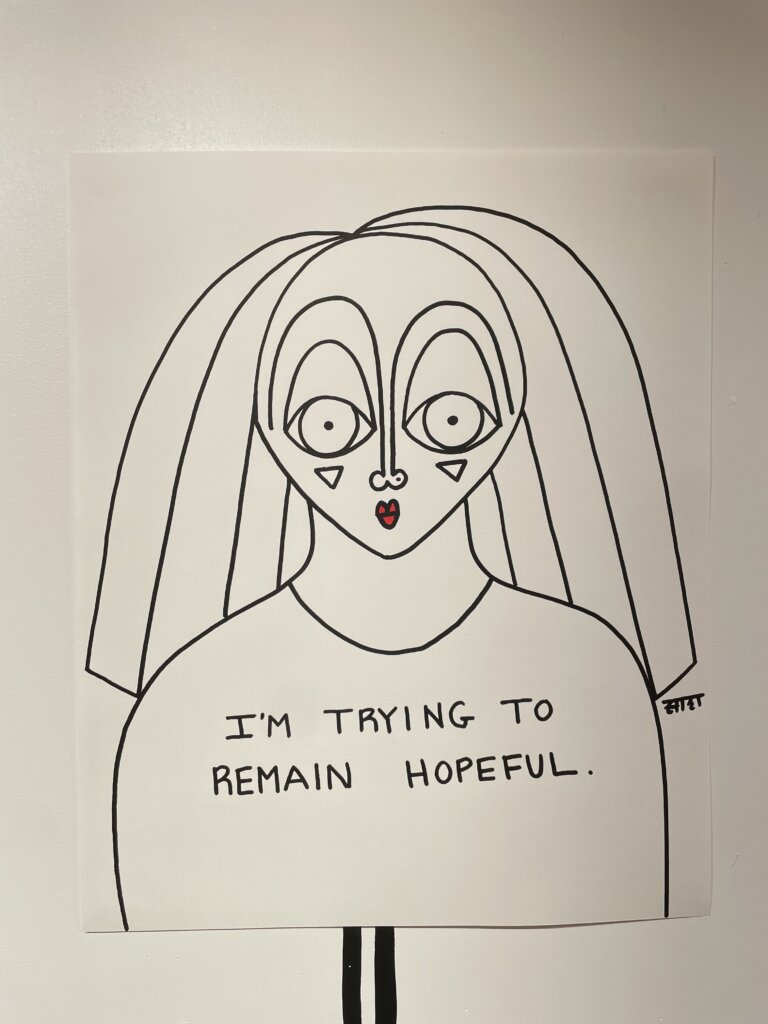

In the mural, the picket signs are Erenthal’s trademark self-portraits, with sayings like “END THE OCCUPATION,” “THE KIDS DIDN’T DO IT,” and “I’M TRYING TO REMAIN HOPEFUL” written on the figures’ chests in a multitude of languages. The wide-eyed portraits seem like glimpses into the soul of a peace activist in the middle of the war. One portrait wears the Arabic script for “broken heart,” and another says “PAZ,” the Spanish word for “peace.”

One of the children depicted at the protest holds up an actual kid’s drawing that has been affixed to the wall, with a frowning stick figure and the words “It’s not our fault” scrawled in blue, red, purple and green. Another figure has a baby strapped to her chest; another holds a dog on a leash. The effect of these figures, rendered in 2D and staring intensely at each other, is to invite the viewer to step into a chaotic, diverse community of people, all unified in a basic concern for human life.

“She’s very empathetic,” said Sally Brown, a friend of Erenthal’s who attended the opening. “And it shows in her art.”

A compassionate artist — and babysitter

I agree with Brown, both because I appreciate Erenthal’s artwork, and because I’ve experienced Erenthal’s warmth in a dramatically different setting. Around 20 years ago, when I was in elementary school in Long Island, Erenthal was my after-school nanny, and not yet a professional artist. She was in her early twenties, recently escaped from her restricted upbringing in the Haredi Neturei Karta religious group. I remember her being fiercely independent and curious, listening to me and my 8-year-old friends with more respect than most adults would lend to little kids. She worked for us for about a year, after which we fell out of touch.

Last summer, I was walking around Brooklyn when I passed a drawing of a wide-eyed woman with wavy hair painted in fine lines on a storefront’s window, with the tag “@SaraErenthalArt” next to it. Soon after, I bumped into Erenthal in Prospect Park, and I learned about the artist she has become.

In the last 10 years, she has developed a following for her street art like the piece I saw on a Brooklyn storefront. She’s particularly well-known for her self-portraits, which are often accompanied by heart-on-your-sleeve phrases that encompass political messages — like the ones scrawled on paintings at her recent show — as well as musings on the seasons (“LATE SUMMER FEELS LIKE A BREAKUP”) to friendly advice (“BE SMART AND PROTECT YOUR BEAUTIFUL HEART ”).

On opening night of her new exhibit, young New Yorkers milled about the warmly lit space, contemplating the artwork. In one corner, a group of people intensely discussed Israel’s siege on Gaza — “There is no Israeli left,” someone insisted.

Erenthal said that she hoped that the exhibition, open to the public in the warmly lit back room of the gift store through the beginning of January, would help people to make sense of a polarizing conflict. “I know people who are conflicted in some ways — especially Jewish folks,” Erenthal said. “When they see what I have to say, they feel like they’re in the right, safe space.”

Anti-Zionism and back again

Erenthal wasn’t always critical of Israel — though she was raised among people who were. Neturei Karta, the Orthodox group in which she was raised, is notable among the Haredim for being staunchly anti-Zionist, believing that only the coming of the Messiah should bring the Jews back to Israel.

But Erenthal said that during her childhood in New York — she was born in Jerusalem and moved to Brooklyn at age 4 — anti-Zionism meant avoiding the subject of Israel. “The school I went to cut out the whole section of history books that would talk about the Middle East, just so that we don’t have to talk about it,” she said. “So I grew up with very little knowledge.”

When she was 17, her family returned to Israel. Her parents had arranged a marriage for her, but, sick of her community’s restrictions and pressures, she ran away to the home of less-religious family members the day before she was to meet her would-be husband.

Soon after, Erenthal joined the Israel Defense Forces, a decision she now regrets, both because she came to oppose Israel’s government and military, and because armed service did not suit the burgeoning artist in her. At the time, though, it seemed like one of her only options. “I was a runaway kid. I grew up without any knowledge,” she said. “I had nowhere to go, I was stuck in Israel, I had no money.”

After performing administrative roles in the army for 21 months, she returned to the U.S., where she worked odd jobs — including caring for 8-year-old me — before finding her way towards art. About 12 years ago she began to deeply question the inner workings of the country that had helped her gain her independence.

She remembers talking to Palestinian friends she met in New York’s art scene and being moved by their perspectives, and watching documentaries like 5 Broken Cameras, an account of a Palestinian family in a West Bank village being encroached upon by Israeli settlers and the Israeli government.

In the last decade, Erenthal has visited the West Bank twice — an experience she describes as moving her firmly against the Israeli occupation of the region.

“I feel like I come from an oppressed situation,” she said, referring to her childhood in Neturei Karta. “I’m very sensitive to suffering. And once I started understanding that there is suffering — That’s when I started really questioning.”

Making art after Oct. 7

In September, Erenthal and Del Hierro began talking about creating an exhibition in the store. Del Hierro had long been a fan of Erenthal’s work and the two set a loose date in December for an art show.

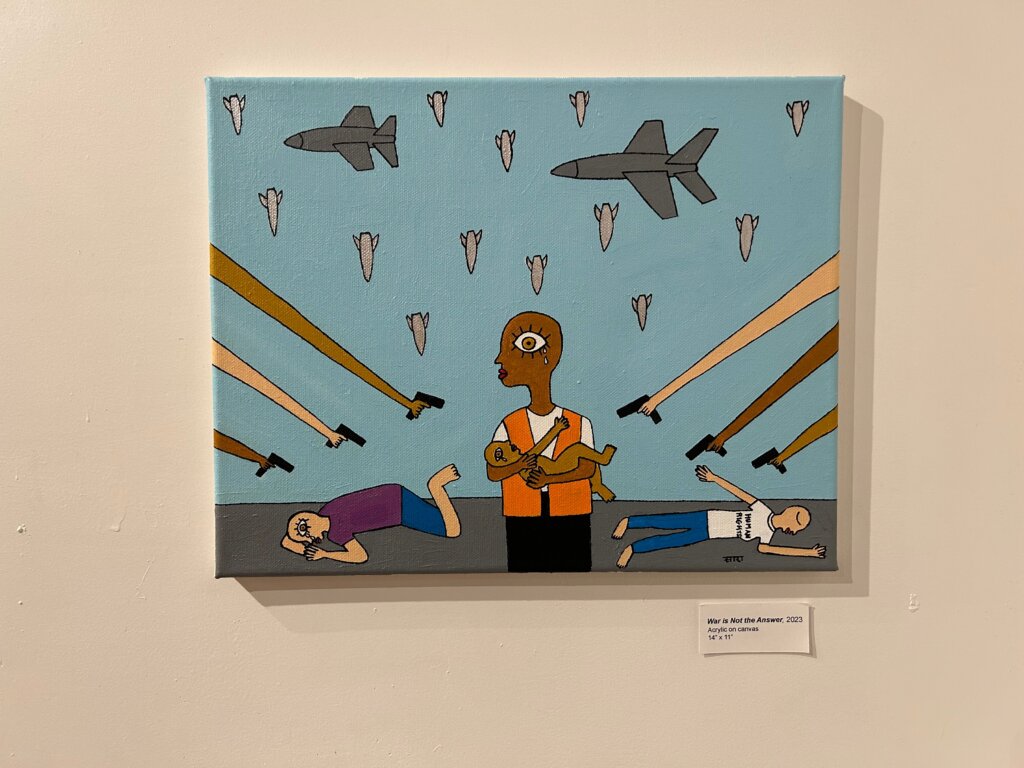

Then, on Oct. 7, Erenthal woke up to news that Hamas soldiers had launched a series of terrorist attacks that would claim the lives of over 1,200 Israelis, mostly civilians. “I was insanely devastated,” she said. “I couldn’t believe it — that someone could do something so evil to innocent humans.” At the same time, she felt that Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories was a “ticking time bomb” that was bound to lead to something catastrophic. In the following weeks, as Israel launched a siege on Gaza that has claimed the lives of at least 18,000 Palestinians, mostly civilians, according to officials there, Erenthal found herself hurting for both Palestinians and Israelis, and began attending protests calling for a permanent end to the war.

Processing painful news, attending protests, and making artwork left Erenthal feeling exhausted. At one point, Del Hierro told her that if she didn’t feel up to following through with the exhibition, she would understand. But Erenthal pressed on, inspired by the protests she had been attending and determined to share her message. People needed a collective space to grieve, hope, and organize, she said, so working on the exhibition was “the right way to spend my time.”

She worked up until the last minute on the mural, calling on the Artery’s customers to help with translations to Arabic and enlist their kids in making art.

On opening night, some of the viewers I spoke to said they were comforted by the immersive embrace of Erenthal’s work. Emily Goldberg, a 24-year-old Jewish Brooklynite who grew up seeing Erenthal’s street art in Park Slope, called the inscriptions on the wall “common sense” and “human rights,” and said that she felt privileged to be able to enjoy Erenthal’s art in peace when so many were at war.

Erenthal’s friend Sally Brown loved the painting that bears the phrase “TOGETHER.” “The world is having a lot of problems with polarization,” she said. “There’s no hate here.”