The 99-year-old Jewish bomber pilot, my father, Amelia Earhart and me

A chance encounter in Riverside Park led to a friendship between a journalist and an elderly aviator

Si Spiegel with the East Coast Doughboys in Central Park, November 2020. Photo by Svetlana Blasucci

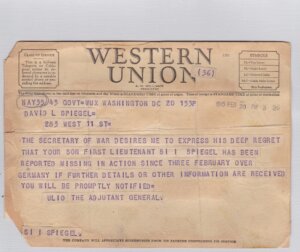

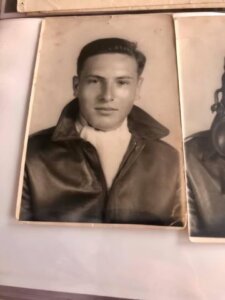

A bomber pilot died Jan. 21. Not in action over Europe but in his home on the Upper West Side, ending a bumpy journey that included a Jazz Age childhood in Greenwich Village, battling Hitler, busting out of detainment by the Russian Army, marrying a Japanese-American woman who had been held in an American internment camp, raising a family, and starting an artificial Christmas tree company which made him a multimillionaire. As the unlikely journalist who brought this remarkable man’s story to The New York Times, I was on the ride for just the last few years, but I considered 99-year-old Si Spiegel a friend, not a source.

We met for the first time right in front of the imposing statue of Eleanor Roosevelt at the southeast corner of Riverside Park and West 72nd Street. Si was in jeans, black sneakers, gloves, and a hooded sleek black parka, and stood out as an unassuming historian passionately discussing Eleanor Roosevelt’s aviation advocacy and her support for the Tuskegee Airmen with a woman he had just met on his walk. I had just signed a contract to write a biography about Amelia Earhart for Viking, and was mesmerized by this elderly man’s obvious knowledge and enthusiasm for aviation.

That day marked my first venture outdoors for an extended period in two grueling weeks. My beloved father Julius, 99 years old and in rapid health decline, had been admitted to an Upper East Side rehabilitation center. After days filled with the responsibilities of caring for him, I had intended my walk in the park as a brief escape from consulting with doctors, making sure my dad ate and that he wasn’t too salty with the nurses.

I stopped to listen to the man in the parka long enough to convince myself he was around my father’s age, but unlike my long-disabled father who was partially paralyzed at 20 after a disastrous New York hospital screw-up, this nonagenarian had undoubtedly been in World War II, and perhaps even within the specialized realm of Army aviation. Still, I doubted he was a former pilot due to the fact that the job of pilot was mainly off-limits to Jews.

Finally, this chronic native New Yorker eavesdropper couldn’t resist jumping into their conversation. To my surprise and the other lady’s delight, the silver-haired gentleman said that he’d been a bomber pilot in WWII, and had flown 35 harrowing missions over Europe. This is when I first heard about his heroic escape on his 33rd mission and learned that he was the only one left of his crew and the only surviving member of the 490th Bomb Group.

“Listen, I’m a journalist; mind sharing your story with me at length?” I asked, bubbling over with what my friends call my “caffeinated optimism.” I offered to meet him at his place or over coffee nearby, flashing my brightest smile as I handed him my card. He gave me a wary glance, and slipped the card into his parka.

Later, at the rehabilitation center, I shared the story of my windy walk with my bored and ailing bed-bound father. I doubted “my pilot” would ever call. I told my dad that, although I felt comfortable telling the civilian tale of Amelia Earhart, I might be out of my lane this time trying to take on a bomber pilot. My dad asked me to fill him a plastic cup with Pepsi and then asked me to sit closer to him as he had something to say in a weakened voice. “Do both! If not you, who? Men our age die. And you’re a damn good writer!”

I sheepishly then admitted that this crackerjack journalist hadn’t gotten his name and details — the man had to call me if we were to continue; my dad laughed and sent me one of his famous “Schmuckograms” from his bed. (His neologism.) It was nice to hear that raspy laugh again, even if it was at my expense. After another sip of Pepsi, he dispatched more wisdom– “You can find him. Your story is for The New York Times, that’s who. That’s where this goes.”

A few hours later, the then-95-year-old Si Spiegel called. Apparently, he had examined my business card and discovered my address was the exact Lower East Side apartment building where his parents spent their final years. His parents were fellow ILGWU (International Ladies Garment Workers Union) members and probably knew my union activist grandparents, who were the first tenants of my apartment from the building’s opening week in 1955 after my dad bought them a co-op for $8,000. This serendipity, he confessed, was the sole reason he reached out. “I’ll grant you an hour for an interview — let’s see where it leads,” he said.

My dad spoke with my busy brother, who agreed to spend the morning with him.

News from Pearl Harbor

Si’s apartment, in a luxurious complex near Lincoln Center complete with a doorman, swimming pool, and a stunning slice of Central Park if you happened to be standing in the right spot, was funded by what he called “my Christmas tree money”— a term whose significance would only become clear to me as I delved deeper into his later career.

As a veteran old Jewish man whisperer, I smartly arrived with a box of Mallomars, and could tell I had already scored big points. When I hit the record button, Si started his story about high school at Straubenmuller Textile in Chelsea. He said he’d been with his family in their car, proud of its 35-mph speed and radio when they heard the news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, a place they’d never heard of before. This left them worried and uncertain about what it meant for their future.

Straubenmuller was my mother’s school, too, and finding out Si was in her class was another surprise.

“That’s crazy!” Si said with a big grin.

I tried to get Si to tell me his story chronologically, but he wanted to get things out as he remembered them. “Stop interrupting me,” he said, in a not-mean way. I was used to this tone from taking care of my father. “Better to get whatever I say before I lose it altogether.”

We then journeyed back, not forward: “My name was supposed to be Isaiah —Shiah in Yiddish. The guy who filled the birth certificate left out the H, so I became Isai, which became Si…”

After an hour, our chat finally ventured into his military days, sprinkled with jargon I barely grasped. I playfully challenged him to spell “Flugabwehrkanone” (anti-aircraft cannon), and with a grin, he spelled it out without missing a beat. Si told me that he still had nightmares of being hit by flak, which he described as anti-aircraft shells thrown and shot up into the air by a cannon. He told me his odds of survival had been terrible. Over 50,000 American airmen lost their lives in WWII, mostly on B-17s and B-24s. The Eighth Air Force suffered 40 % of all casualties in the air war.

When we were done, he had given me three hours, not one, but he had to break for his workout with a trainer. For most of the interview, he had remained standing, conversing with an energy surpassing many of my Gen-X peers.

He agreed there were follow-ups needed, but before I left, he wanted to make sure he showed me his military decorations.

‘Your dad would be so proud’

Si remained healthy, but other bad things happened; my father died in January 2020 and then the onset of the pandemic in March put everything on hold. The grief and guilt intertwined with the delay in moving Si’s story forward.

When I finally had some energy, I had a wonderful socially-distanced Central Park walk with Si and we talked about democracy and had an outdoor pandemic lunch. When he took off his mask to eat, he joked, “No kissing!”

One day when grief was at bay, I remembered my father’s words and contacted an editor at The New York Times. An email came back in minutes — he loved the idea and wasn’t worried about a time peg. “The peg is that he is a living WWII pilot, a Jewish one. Any day is the right day!”

I celebrated this news with Si at Pomodoro Rosso, his favorite Italian restaurant on Columbus Avenue with a glass of champagne. “Your dad would be so proud,” Si said.

‘The last time I saw Si’

While crafting this memory piece for The Forward, a newspaper Si grew up watching his parents read and one he continued to read in English until his death, I called my friend Kevin Fitzpatrick to see if he had anything to add. Kevin, president of The Dorothy Parker Society and the subject of an article I wrote about the effort to bring Dorothy Parker’s ashes back to New York City from a Baltimore parking lot, was also a former Marine and part of a living historian group that regularly played homage to World War I sites. Kevin had joined me for lunch with Si several times, and wanted to make sure I added how we plotted ways for Si to be chosen as the Grand Marshal for the 2020 Veterans Day Parade. Si was thrilled when we got the green light.

However, the pandemic had other plans, and the parade was canceled. There would be some kind of motorcade, and Si was invited for a drive-by. Not so thrilling.

Undeterred, Kevin arranged for Si to meet in Central Park with the East Coast Doughboys, his WWI living history group. On a drizzly, overcast Veterans Day, typical of New York’s November, about 15 living historians and a half dozen friends gathered near the mall by the Naumburg Bandshell, donning their uniforms. The highlight was the arrival of James Hendon, the New York City Department of Veteran Services commissioner, who came to honor Si with a special wreath-laying ceremony at a flagpole dedicated to city employees who were veterans. Surrounded by his family, including two grandchildren of Japanese-Jewish heritage, Si stood as a beacon of resilience and history.

Everyone there was eager to hear from an authentic WWII B-17 bomber pilot, asking questions about engines, airplanes, and locations through their masks. Si, then 97, embodied the spirit of those he served alongside, eager to share his experiences and represent the friends and fellow veterans who couldn’t be there.

“During World War II,” he soon said on TV from a motorcade car driven by his son with me in the back seat — “When I was a bomber pilot flying B17s — none of the crew who flew with me are still living — I am the only survivor — and I am representing them in everything I do. I am riding for those who fought with me in WWII.”

Months after the story had faded from the headlines, Si told me he felt a twinge of sadness as his brief spell of “notoriety” seemed to wane. Looking to lift his spirits, I invited him to join me in June 2022 as my plus-one for a private screening of Gabby Giffords Won’t Back Down, a documentary on the life of Gabby Giffords, the former Jewish congresswoman, directed by the same team behind RBG and Julia.

Unbeknownst to me at the time, Giffords’ grandfather Akiba Hornstein was a Jewish immigrant from Lithuania who had changed his surname to Giffords to escape antisemitism. During the event, Giffords’ assistant ensured that Si received a generous amount of attention, which he clearly appreciated.

“That was something,” Si remarked, a note of extra warmth in his voice, as we made our way back to his doorstep.

By now we were only friends, and his new goal, he said, was to live long enough to see his name in my forthcoming Amelia Earhart book, which won’t be out until 2025. Over the years we spoke at length about Earhart and the kind of planes she flew, and his theory about her disappearance, and it tickled him he would be listed as a source.

The last time I saw him was on Dec. 24, 2023, about a month before he died in his home. He was thinner and said the end was near. Of course, I have no idea what ran through his head in his very last days to follow but I remember well the day he told me that around his 12th or 13th mission, his nerves gave out. The term he preferred to use was getting scared.

“When you are that age, you always think, I’m not going to die,” he said. “Other guys are going to die. But not me. I’m not going to die. I’m too young for that. Then, there is a day when you think, ‘Oh yeah, I could really die now.’ That’s what getting scared is. Most guys got scared earlier on. When it happened to me, my knees shook, and I thought, boy, I was stupid.”

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article listed the Purple Heart among the many honors Si Spiegel received. Since we were unable to verify this fact, the reference has been removed.