First PersonWhat our son’s short life taught us about faith and tradition

We’re Jewish, but found strength in other’s prayers — from Rama to rugby

Pictured above with his son Nadav, author James G. Robinson describes how his family found their strength following Nadav’s diagnosis. Courtesy of James G. Robinson

This essay is adapted from the author’s memoir, More Than We Expected: Five Years With a Remarkable Child.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel once wrote that we must simultaneously inhabit two realms: that of the real, and that of the ineffable — what is beyond our understanding. There is nothing that upsets this balance more than a life-threatening medical diagnosis.

When our son Nadav was born with a serious heart defect, I found myself staring into the unknown. But instead of shaking my faith, the experience redefined it.

I grew up in Brooklyn, in a family where belief in God was less important than knowing who your people were. My parents were raised Orthodox in Australia and New Zealand, outwardly assimilated, but inwardly traditional. They moved to New York a year before I was born. I remember attending services at our Orthodox shul, my dad kibitzing with his friends in the back of the men’s side, the rabbi periodically banging his fist on the bima to get their attention.

I’d hold a prayer book filled with dense clusters of Hebrew text, the letters tracing ancient patterns across the page. I mostly deferred my religious obligations to the mumbling men around me, flipping pages to catch up whenever I heard a familiar melody. While I didn’t always understand what was going on, the prayers connected me to my ancestors. I found myself able to rise beyond the fuzziness of the individual words to find comfort in the shared energy of the room.

Years later, when our baby boy was diagnosed with a serious congenital heart defect, we reached into that shared energy of our past. We gave him a second first name: Moshe, in memory of my wife’s grandfather, who spent four years fighting Nazis as a partisan in the Belarusian woods. Our son’s chances of survival seemed similarly slim.

Joining the community of heart parents and cardiac kids brought us face to face with unfamiliar traditions, tinged by talk of warriors who were “blessed” and angels who’d gone to “a better place.” We held this unfamiliar faith at arm’s length. But when others reached out, it was hard to say no.

Early on, we met a little girl who’d survived a particularly difficult surgery. When she left for home, her joyous cousins celebrated by handing out embroidered angels to everyone in the ward. Though it wasn’t our tradition, we hung ours on Nadav’s IV pole. And when he was finally discharged from the hospital, it came home with us, too.

The monkey god and the god of rugby

Nadav had three heart surgeries before age 4. Not once did I believe that their outcomes depended on divine intervention. But I still offered a blessing before each procedure. It was the same blessing my Australian grandmother sang softly to us whenever we were together for Shabbat dinner, her hands pressing down on our heads, firm and strong.

“May the Lord bless you and keep you,” I’d say as she had said, pushing away my son’s light brown curls. “May the Lord shine his countenance upon you, and be gracious unto you. May the Lord look kindly upon you and give you peace.”

After his third surgery, we decided to bring Nadav, his twin Yaniv, and their older brother Gilad to meet our many relatives in Australia. Unfortunately, the trip went terribly wrong. Nadav developed a blood clot, and we suddenly found ourselves stuck in a strange hospital on the other side of the world. He needed an emergency operation that lasted 14 hours.

That night, we called our cardiologist in New York. We could hear her eyes moisten over the phone; she was too far away, unable to help. “I’m praying for him,” she said.

“To which God?” I asked, knowing that she was a devout Hindu.

“All of them,” she replied.

For some reason, I pressed her further. “If you could pick just one,” I asked, “who would it be?”

“Hanuman,” she said, definitively — not knowing whether to laugh or cry.

When we hung up, I Googled “Hanuman.” It was the monkey god, and in almost every picture, he was depicted holding his chest open, blood dripping out, revealing the two deities — Rama and Sita — he was sworn to protect.

I could not think of a better guardian for our son, whose bloody chest was also open, needing protection. So I printed out one of the images and taped it above his bed. I suppose I thought it might help us feel closer to the doctor we knew best, and perhaps conjure up any hidden power the cosmos might have left.

I don’t know if Hanuman had anything to do with it, but Nadav made it through that night, and many more.

He remained intubated and heavily sedated in the intensive care ward for weeks, stable enough for us to settle into a predictable rhythm, but still stranded far from home.

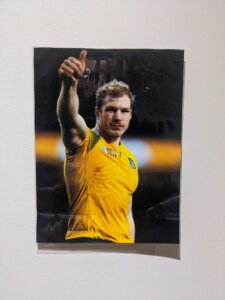

Knowing we were Jewish, one young resident expressed surprise at the picture of Hanuman taped above Nadav’s bed. I jokingly asked if there were any other deities he might recommend. “You should put up a picture of David Pocock,” he said with a smile.

“Who?” I asked.

“He’s a rugby player,” said a nurse, laughing.

I explained that I was thinking more along religious lines.

“Oh, you don’t understand,” said the resident. “Rugby is my religion. And I worship David Pocock.”

So, David Pocock went up on the wall, next to Hanuman. I made sure I picked an especially tough-looking picture — his nose bloodied, body bruised, ready for whatever came next.

‘Jesus was Jewish when he was born’

We returned home nearly three months after the clot, a miracle made possible by an amazing cast of medical professionals. If there was a divine hand involved, I could not discern it. But I’d come to accept that there were some things beyond our understanding, and I found myself more welcoming of other faith traditions.

Soon it was the Jewish High Holidays — a time when I am most conscious of the gap between us and the rest of the world. We’d walk to synagogue past people doing what they normally do — moms pushing strollers; kids on phones; workers with double-parked trucks. They inhabited a parallel universe in which this was just another day, while we stepped back from our daily lives to ponder the ineffable.

Later that fall, those neighbors would prepare for their own holidays, the world suddenly awash in pine needles and tinsel. My wife and I had always felt it necessary to draw a line between us and the rest of the world at Christmastime, reminding our kids that these traditions were not ours. But that year, we welcomed one Christmas tradition into our home, like we had the embroidered angel from Nadav’s first surgery.

Some friends of mine always went caroling around the neighborhood. That winter, we invited them to come in and sing for us, too. They arrived close to the kids’ bedtime, and after they stamped the snow off their feet, I half-jokingly asked if they knew any non-Christmas songs. “Not many,” one said. “But it should be OK. Jesus was Jewish when he was born, wasn’t he?”

Their beautiful harmonies — so different from the lilting melodies we’d sing when kindling Hanukkah candles — filled our apartment with an unexpected light. The boys sat, transfixed. I didn’t mind at all.

Other hearts beating in the room

Nadav died that January, suddenly but not unexpectedly. The Jewish rituals of mourning guided us through the aftermath of death as surely as Nadav’s doctors had helped us navigate his life.

Every tradition had a spiritual explanation. I also found that behind every custom was a good dose of common sense, centuries-old guidelines to help mourners grapple with grief.

We followed the rules: The body was buried as soon as possible (no space to linger on the shock of the death), in a simple wooden casket (no need to be stressed by choices), after which you are encircled by friends bearing food (cooking being the last thing on your mind).

As mourners, we were surrounded by our village, relatives and neighbors and co-workers lending support as best they could. Nobody, of course, knows quite what to do, or say — sometimes causing odd, tangential conversations, sometimes prompting awkward silences.

But as someone later told me, “the important thing is to be there.” It was good to just feel other hearts beating in the room.

‘We will make sure you don’t go alone’

After the seven days of shiva, I returned to my job as a data analyst at The New York Times. Condolences had flooded in from many of my colleagues, even some I did not know. They’d recognized Nadav’s name as Hebrew and decided to reach out; some offered to arrange a minyan, the quorum of 10 required for daily Jewish prayer, at the office for me to recite the Mourner’s Kaddish. I demurred. It was a kind gesture but unnecessary, since there were several services within a few blocks of our Times Square headquarters.

“In that case,” one colleague emailed, “we will make sure you don’t go alone.”

And so it was. Each day around lunchtime, I’d head to the building’s lobby to find my Kaddish escort. They’d introduce themselves, we’d shake hands, and on the 10-minute walk to the synagogue, I’d tell them Nadav’s story.

By the time we reached the shul, my companion would inevitably have tears in their eyes. I’d find myself comforting them: assuring them that Nadav’s short life wasn’t a tragedy, but a blessing; explaining how much I appreciated their company; and saying how lucky I was to be able to share my son’s story with them.

Our tradition demands that we recite Kaddish in a group. What a smart idea: Without that obligation, I would have felt unbearably alone.

Reciting this ancient prayer connected me to my Jewish community and our Jewish traditions. But Nadav’s journey had shown me that I didn’t have to share people’s faith to draw strength from them.

Whether they worshiped Rama or rugby, those around me were also wandering the realm of the unknown. And that was enough to bring us together in the real world, wrestling with the things that make us human.