Finally, a new hub for people who want to study the language and history of Ladino

The American Ladino League celebrates a language that was the mother tongue of generations of Sephardic Jews

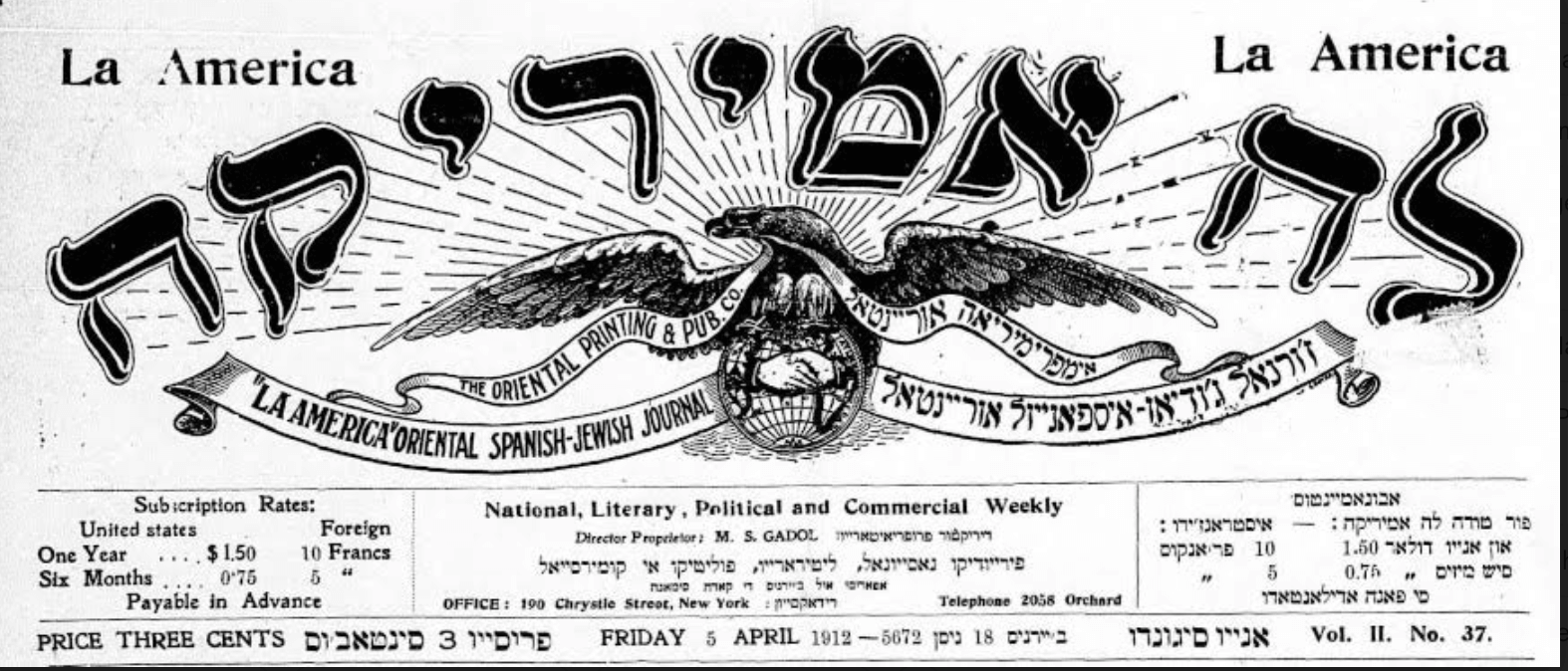

From a 1912 edition of La America. Courtesy of American Ladino League

The American Ladino League, which describes itself as a “new hub for Ladino language learning and community,” is a creative and multi-layered response to the growing interest in learning Ladino — and especially, the explosive interest in online Ladino classes that happened during the pandemic, where some lively classes had hundreds of students from all over the world.

Ladino is one of the most important diasporic languages in Jewish history. Also known as Judeo-Spanish, or Judezmo, Ladino is a Romance language — a variety of Spanish that includes both words and phrases from Hebrew, Turkish, Arabic, Greek, French and Italian. It originally developed in medieval Christian Spain; after the expulsion of the Jews in 1492, it moved along with Jewish exiles, and then developed independently of Iberian Spanish. For 500 years, Ladino thrived, and was the mother tongue of generations of Sephardic Jews.

“There is an array of Sephardic religious and cultural programming in the United States, but no national coordinating body to support language learning specifically,” said Bryan Kirschen, a professor of Hispanic Linguistics at Binghamton University, and co-director of the American Ladino League. “We see our parallel in organizations like the National Authority of Ladino in Israel, the Ottoman-Turkish Sephardic Culture Research Center in Turkey, and the Sephardic Cultural Center in Argentina. These are vibrant, community-driven centers and excellent models for the presence we hope to establish.”

That word “center” is important in how the American Ladino League sees itself.

“In founding the American Ladino League, we are creating a hub that brings together people who already speak or want to learn Ladino, as well as those who are interested in learning about the language and its historic role in Sephardic culture,” Kirschen said.

The ALL has an ambitious plan to support students and teachers of all ages and levels. Over the next five years, it hopes to have a podcast; grants for translations into and out of Ladino; and community building through a “Ladino Lounge.” It’s also working on creating evaluation systems and conferences for students and lifelong learners.

“We want to show Ladino in as many formats and fonts as possible to make it accessible and more familiar-feeling,” said Hannah Pressman, one of the organization’s three co-directors and also Director of Education and Engagement at the HUC-JIR Jewish Language Project, which preserves endangered Jewish languages. (Full disclosure: this columnist is on the board of the Jewish Language Project, but is not affiliated with the American Ladino League.)

“That carries over to the posts we’re putting on social media,” Pressman said. “We’re taking full advantage of the solitreo font that Bryan created a few years back and posting graphics that include Rashi letters, solitreo, Latin transliteration, and English translation.”

The American Ladino League views this moment as critical in the history of Ladino in America. It plans to “provide accessible, consultatory, collaborative, and financial support for innovative approaches to teaching Judeo-Spanish across generations and on multiple platforms,” according to its website, which is bilingual Ladino-English.

Scrolling through the Ladino and English translation is a great way to get a feel for the League, and to see how its materials are accessible to those at all levels of Ladino knowledge.

“I am a heritage speaker; my mother’s family is from Turkey and the island of Rhodes,” Pressman told me. “However, in many Sephardic communities, Ladino skipped a generation or two: It wasn’t taught formally or passed down informally because people were trying to assimilate into the majority culture — much like Yiddish in America, in that regard. So when I study Ladino, I am learning things that I can share not just with my kids, but also with my mom, who is now learning the language for the first time.”

For Pressman, what’s special about the American Ladino League is the chance to work with others — teachers and activists — who are devoted to reviving Ladino.

“Bryan Kirschen was my teacher for the online classes I took during the pandemic,” Pressman said. “Rachel Bortnick grew up in Izmir and knows Ladino as a native language. In fact, her father knew my great-granduncle, the Turkish Jewish historian and writer Avraham Galante.”

That family connection is not that unusual; in the Ladino classes I have attended on Zoom, participants sometimes discovered that they were distantly related. Many participants, like Pressman, were trying to understand their own history.

For those who want to see Jewish languages thrive, it’s exciting to see a new organization devoted to Ladino, and it’s a worthy companion to existing American organizations that support Yiddish, like the National Yiddish Book Center, and Hebrew at the Center for Hebrew. If people want to get involved, they can visit americanladinoleague.org and add their name to the mailing list.