He was the heir apparent to Franz Kafka and Ralph Ellison and pioneered the idea of ‘wokeness’ — how did he just disappear?

For decades, Barry Beckham — whose baseball novel ‘Runner Mack’ was inspired by Kafka — has been hiding in plain sight

The work of Franz Kafka was a major influence on Barry Beckham’s Runner Mack. Graphic by Matt Litman

America started noticing Jackie Robinson and Franz Kafka at about the same time.

That’s a fact to which I awoke as a long-time baseball guy — a Dodgers fan for 23 years living in Los Angeles, aware of Dodgers history back to Brooklyn — and as someone with Kafka’s works on my shelves since my teens. But I never, ever thought I’d cross a bridge between sports and The Trial, between Robinson’s run across the major league color line in 1947, and the first time Kafka translations ran off American printing presses about a year earlier.

But those two different debuts frame Runner Mack, an outstanding but mostly forgotten novel—regarded by those who know it as the first African-American baseball novel. Barry Beckham’s novel appeared in 1972, long after Robinson retired, long after “Kafkaesque” became a word to describe a bureaucratic run-around.

Beckham’s hero is Henry Adams, a Black baseball phenom who wants to play on a major league team. He’s moved to an unnamed northern city with his wife, Beatrice, to do so. It never happens. His life turns to baseball-obsessed futility, a dream deferred. Woven through Adams’ endless trials is Kafka’s terrifying vision of universal injustice, state violence and normalized psychic trauma.

In The New York Times, Mel Watkins, a critic and the first Black staff editor of the Sunday Book Review, praised Beckham’s story of a ball player who joins a plot to blow up the White House, calling Runner Mack “an allegory that both illuminates the despair and recurring frustration that has characterized Blacks’ struggle for freedom and brilliantly satirizes the social conditions that perpetuate that frustration.”

Watkins described resonances of both Kafka and Ralph Ellison in the novel, concluding that it “should confirm Barry Beckham’s place among the best of American contemporary novelists.”

That place never solidified for Beckham. The New York Times named Runner Mack as one of the best books of the year. It was nominated for the National Book Award. Its sales were poor, some admirers believe, because Beckham’s thrilling prose shared an existential vision as bleak as that of a man tried for no clear cause.

Runner Mack still gets written about from time to time. A reporter or scholar will find it and offer a new view of its timeliness or argue for its literary value. In July 2020, about a month after the George Floyd murder, Adam Langer, a novelist and executive editor of the Forward, included Runner Mack in a New York Times essay about Black authors who wrote thrillers around revolutionary politics and embodied the “struggle to achieve lasting progress on civil rights in America, as well as the danger of creating speculative fiction that’s a little too truthful for comfort.”

GerShun Avilez, a professor of English at the University of Maryland who teaches African-American literature and is one of a few scholars who have written about the work’s importance to Black culture as a mirror to history, recently told me that Runner Mack is “a defining book of the late 20th century if you think about what is happening to Black America at that time.”

Today, in an era when wokeness has become a part of conservative political rhetoric, while publishers have woken to the increasing popularity of previously marginalized authors, it is worth recalling how a work about wokeness to the racist limits of American society sank from view.

The writer himself sought to create the great Black American novel, and forged it from his journey as a Black student, corporate figure and educator. He found himself at Chase Manhattan Bank, working to expand chances for high school drop-outs in a 1960s Harlem battling poverty, police brutality and other problems that plagued African-Americans at home, even as many were drafted to fight in Vietnam.

Beckham witnessed the hunger for change, the slowness of it despite certain progress and the militancy that awoke as the Civil Rights Movement yielded to the Black Power Movement. His novel about Henry Adams’ radical wokeness took root in a New York City battered by racial conflict and surging with rebellious energy among Black writers and artists. And he wrote it in the wake of student revolts across the nation, including Brown University, where he taught, for equality in education.

How did a Jewish writer haunted by cosmic injustice become part of all that?

It’s one of the questions that compelled me for over a year, as I ran down answers for this story about a novel and a writer excited about puns as a way to make people think.

Meeting the man

I hadn’t heard of Barry Beckham when I met him by sheer accident in October 2021, at Trattoria dell Arte, an Italian restaurant on Seventh Avenue, across from Carnegie Hall.

The place had a touch of free-spirited absurdity, including a large comic nose that juts like surreal sculpture from a wall. It and the rest of the décor was designed by Milton Glaser, the well-known Jewish artist-designer. I had eaten there just once, years before.

A few of its walls are hung with portraits of leading Italian writers from the 20th century, black-and-white wood cuts made in a German Expressionist style. Examining these portraits, I leaned in for a better look at Luigi Pirandello, the experimental early Modernist playwright best known for his play, Six Characters in Search of an Author.

A relaxed-seeming, older couple was eating lunch, and I’d gotten uncomfortably close to them.

I stepped back, apologized and explained that these were writers whose work I enjoyed.

The man’s eyes widened. “Yes, I am familiar with these writers,” he softly declared.

I heard an intriguing clarity of confidence when he said that: familiar. His tone suggested shyness, maybe that in another situation, he’d want to avoid attention, but not this one. He said it as if he belonged to these writers.

I asked if he wrote, and he answered, “Yeah, I’m a writer,” but added in a voice that dramatized regret that he wasn’t at his desk much due to back problems. We talked about the figures in the portraits, many poets, and he said: “I’ve known poets, but I don’t write poetry.”

Before we parted, with a touch of proud flamboyance, he whipped out a business card: “Beckham Publications.”

Discovering a semi-forgotten writer

With Beckham’s business card beside my keyboard, I ordered some of his books and researched him online.

He had published four novels, along with the 1972 play Garvey Lives!, which The Washington Post and other outlets credited for pioneering the idea of wokeness as a term for an awakening by African-Americans to the realities of their lives in America.

I wrote Beckham an email saying I’d enjoyed meeting him. I didn’t hear back.

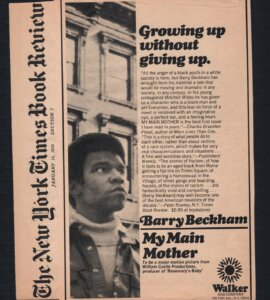

Beckham’s debut novel, My Main Mother, was published in 1969 by Walker & Co., a respected New York house. It is now put out by Beckham Publications. Its cover bears the painted image of a Black woman with her head tilted at an intriguing angle, her hair elegantly but plainly coiffed, eyes sensitive and alluring.

I read late at night, often, in bed in my apartment on the Upper West Side, a single light over my shoulder and the quiet of the apartment seeping around my ears.

Beckham’s first-person narrator, a boy named Mitchell Mibbs, starts by saying he’s sitting in “an old Ford wagon,” somewhere in the woods of Maine, that the car was a gift from his late Uncle Melvin, “who died before I killed my mother.”

I was shocked, yet engrossed by a scene in which Mitchell tries to sleep as he lays on the same bed where his mother has sex with her lover. I enjoyed the calm intensity with which Beckham’s prose took me into Mitchell’s beleaguered, wondering mind.

Beckham kept me connected as Mitchell is admitted to Brown University; his first semester there turns into a nightmare of alienation as Mitchell finds himself to be one of few Black students on campus; as his mother disappears in New York; as he and his uncle head there to find her; as he tests his ambition to play jazz as a drummer (it goes badly); as he discovers Allen Ginsberg’s poetry; as his first semester is shattered when his uncle dies; as his mother and her boyfriend weave a plot to steal the money his uncle left him, and as he kills his mother (I won’t spoil it by saying how).

The novel’s prose had a strange, appealing clarity. It was suspenseful, fast moving. It held me with detailed sensations of love and pain. Mainly, I felt it showed nerve for Beckham to make his debut with a novel about matricide. That, and the title was a pun.

Next, I read Runner Mack, Beckham’s second novel. The novel’s title, like that of My Main Mother, suggested multi-sided word play.

The inside flap read: “Not since Malamud’s The Natural has the imagery of our national pastime been used so effectively in describing the human condition.”

The beginning didn’t seem like any baseball novel I’d read:

The Dentist was holding Henry Adams around the neck with one hand while the other hand held the medicine dropper.

“Come on. It won’t hurt. What’re you scared of?” Then he squeezed the dropper and a tear of water plopped on Henry’s forehead. The water was boiling, and Henry grabbed onto the arms of the dentist’s chair as the pain bore into his forehead. “It doesn’t hurt, what are you jumping for? Take another drop.”

Beckham’s finite details attached smoothly to infinite frightening possibilities, a sensation that, to me, recalled Kafka. The dentist’s treatment, instead of healing, was an attack, one aimed not at Henry Adams’ teeth but at his mind — no drill, no anesthetic, but water, stuff of life. This water was no life-creator, no joyous bestower of blessings. It was a torture.

Henry Adams awakes from what turns out to be a nightmare into the cruel experience of actual liquid shit dripping from a real leaky pipe in the ceiling of his cold tenement apartment and onto his face. It feels like New York though the city isn’t named: “And woke up with something brown and wet running over his face.”

Adams’ disgusting morning reminded me of how Gregor Samsa wakes up in Kafka’s novella, The Metamorphosis, about a traveling salesman in an unnamed European city who has his own anguished awakening when he finds he’s turned into an insect.

But instead of Kafka’s insect who is at odds with a family, Beckham gives Adams a form and outrage that are all-too-painfully human.

Runner Mack, about an athlete who can’t get to play his game, appeared six decades after Kafka wrote Das Schloss (The Castle), about a land surveyor named K. who is subject to the powers of a fortress he can never enter.

I also found echoes of Der Prozess (The Trial) in which Joseph K., Kafka’s main character, is arrested one morning for no specific cause. Beckham, like Kafka, is a writer who wrings a strong sense of symbolic meaning out of relatively ordinary situations — a job interview, a subway ride, romantic courtship, a ballgame.

An essay by Mel Watkins written years after his Times review, delved further into how The Castle and The Trial influenced Beckham, quoting an insight by Edwin Muir, translator of The Castle, that for Kafka’s heroes: “There is a right way to life and the discovery of it depends on one’s attitude to powers which are almost unknown.”

These powers pursue Henry in different forms, often horrifying and comic, one being “a very, very big truck” that seems to smile at him and whose headlights wink at him “like two glass basketballs.” It verges out of city traffic to hit him — after which he limps to a job interview — and reappears as the final symbol of adversity at the novel’s end.

Watkins stressed that Beckham makes his own use of Kafka, rejecting that author’s “sustained ambiguity.” Kafka, though he openly writes as a Jew in his diaries, avoids specific Jewishness in his fiction. Beckham, meanwhile, embraces the “Herculean task” of representing “the Black American’s experience and struggle for recognition.”

That a Black writer should identify this distinct totality of rejection in a Black American ballplayer’s struggle with Kafka’s unjust universe came as a revelation to me, and it made to total sense. My mind also wandered to how Bernard Malamud omitted Jewishness from The Natural, his baseball novel. In fact, Henry Adams seemed more Jewish than Roy Hobbs, Malamud’s hero, as I followed his worried focus on the game as a symbol of exclusion.

Henry takes the subway to the Stars’ domed stadium for what he thinks will be a fair tryout, but is bedeviled by an aluminum pitching machine that throws faster than any human possibly could and an electrified ball that causes him to writhe in pain when he attempts to field it. All this reminded me of Kafka’s story “The Penal Colony,” with its sadistic machine that writes on victims’ bodies.

As I made my way further into Runner Mack, night reading turned into day reading. The book made such a strong impression I wondered if the book wasn’t a dream I’d had myself.

Now, I turned a page and Henry was in Alaska.

I thought of Kafka’s Amerika, a novel set in the country he never saw, in which one is suddenly swept from the New York area — to Oklahoma.

For Henry Adams, who has been drafted, this Alaska doubles as a startling absurdist metaphor for Vietnam through a Black soldier’s eyes. It’s an odd war against animals, caribou, polar bear, white animals in a totally white landscape.

He meets a fellow soldier, a Black revolutionary named Runner Mack, who dismisses Henry’s hope of hearing from the Stars, punctures his patriotic illusions, and asks him to join his plot to blow up the White House.

I had planned to read all four of Beckham’s novels before I called him, but half-way through Runner Mack I was gripped by a desire to know:

Who was Barry Beckham and how did he come to write this novel?

The novelist at home

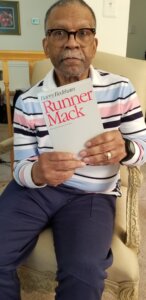

Beckham answered after the third ring. His voice was modulated, almost like an actor’s, friendly but cautious. I described some of my reactions to his novels. “Unless I am hallucinating, you wrote something of a masterpiece in Runner Mack,” I told him.

As Beckham and I spoke, we found common ground in exchanges about other writers we’d both interviewed, such as Nelson Algren, author of The Man with the Golden Arm, in which Algren brought his hard-bitten urban lyricism and natural sensitivity to characters living with drug addiction and other struggles.

Beckham had interviewed Algren for the student newspaper at Brown, where he’d spent his undergraduate years.

Beckham told me that Algren wore Western-style boots when he gave a talk at Brown and that he exhorted students in those early years of the sexual revolution: “When you write, write! When you make love, make it!”

I told him I’d spent three days with Algren once, after I showed up unannounced at his door on Long Island in 1981 to interview him, and he told me: “Writers are like cats. Once you let them in, you can’t get them out.

Beckham laughed and told me another writer story he liked: how playwright Edward Albee told him that “for anyone bothering to create, a social criticism is almost a necessity.”

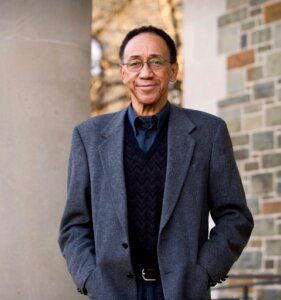

On a hot, humid day last August, I traveled to Beckham’s home in Silver Spring, Maryland, to visit him and spend most of two days talking about his work and life.

Barry and Monica Beckham live in a three-story townhouse in a rural corner of Silver Spring. She is his fourth wife, and the lunch they were having when I first met them was to celebrate their 24th anniversary. Beckham had a son and daughter from his first marriage. His son died two years ago, at 57.

The walls of the Beckhams’ house are full of images of towering figures in African American history: a photograph of Mahalia Jackson taken by James E. Hinton; portraits of Paul Robeson and Zora Neale Hurston. Over Beckham’s head, as we talked for a long stretch, hung a portrait of Frederick Douglass.

Beckham sat in a chair or made his way slowly about, somewhat bent, enduring the debilitating impact of back problems which he revealed stemmed from scoliosis, a curvature of the spine.

“People are amazed, but I have absolutely no pain,” he said.

We were at a round wooden table with a stack of perhaps a dozen books that he was either reading or planning to read. Among them, a biography of the singer Billy Eckstein, two novels by the experimental Soviet-era Russian writer-journalist Sergei Dovlatov, and a study titled: Dostoyevsky, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Kafka: Prophets Of Our Destiny.

As he spoke of his history as a Black man moving for decades through white institutions, his tone became weary, flatly ironic, like a worldly survivor of an illness without a cure.

“I was taking a book out of the library (at Brown). And the librarian asked me if I was a serious professor. What do you think she meant by that?” he asked me.

“What did she mean?” I asked.

“I think she was surprised that I was a professor.”

They called him ‘Kafka’

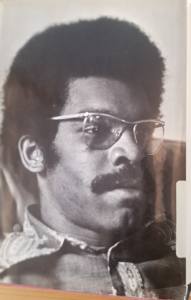

Beckham was born to a single mother in West Philadelphia, a majority Black part of the city, on March 19, 1944. His mother, who’d grown up in a foster home, soon moved them to Atlantic City, New Jersey. Though he had a half-brother, he grew up mostly as an only child in the segregated resort town.

Mildred Beckham worked “as a domestic,” then as an elevator operator in a hotel. She went to night school for hairstyling, eventually becoming a nurse in a hospital.

Beckham said his mother was, “a person who never gave up, and that had a strong influence on me. She said, ‘if you meet an obstacle, go around it.’”

He said his mother was vivacious, attractive; the oil painting on the cover of My Main Mother is her portrait.

In the novel, though, he writes: “Mother’s hair was in her eyes, and she was holding the brown pint bottle of bourbon in one hand,” he writes.

Was that true? I asked.

“Yes. I didn’t downplay it in the novel,” Beckham said. “Literature is an avenue to truth-telling. She wasn’t a drunkard but she could drink. She had many men in her life.”

Beckham grew up in Atlantic City in the era before the casinos got built, and he spoke expansively about the freedom he felt, despite the anxieties of segregation, as a boy exploring the jazz clubs that made the city a draw for leading players.

One club owner often welcomed him and two other underage friends who loved the music to listen.

His writing is filled with references to jazz, spirituals and the blues. Will You Be Mine, his fourth novel, uses lyrics to the 1950s doo-wop hit “Earth Angel.”

By the age of 9, he was writing, he told me. When he was 10, he got a typewriter and a camera for Christmas. He’s written and taken pictures ever since.

Atlantic City High School was where he first took a German language class, and eventually discovered Kafka. “I studied German because I was studying to be a physicist and I knew most physicists studied Russian or German. I wasn’t very good at Russian, so it was German. And that’s how I got to Kafka.”

He became absorbed with the writer’s work, often carrying a copy of one of his books.

“I had classmates who asked: ‘What is a Black kid doing walking around with Kafka?’” he said. “Friends teased me, asking, ‘Why is this Black guy reading Kafka? They called me, ‘Kafka.’”

“I liked the absurdity of it. Nothing was how you expected it to be. Unexpectedness is something I liked in literature.”

He started with the writer’s shorter works, but eventually read his novels, sometimes in German, sometimes English, and came to see ways Kafka’s response to his life in Europe illuminated Black life in America.

“That main character in The Trial was in a world that was treating him in a way that related to the basic unfairness in the experience of being Black,” Beckham said. “I read it and wondered: How can you go to a court and be in a labyrinth? How could he be treated that way? And yet it was happening.

Black writers, he said, weren’t taught in his high school English classes. “No Black writers were taught at Atlantic City High School, and there were no Black teachers,” he said, adding that he later discovered the work of Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright and other Black writers through friends.

He also read baseball novels, taking them out of the nearby Atlantic City Free Public Library, where he told me he was a constant visitor.

“I wore that library out,” he said. “They should have charged me rent.”

He played Little League baseball in Atlantic City, but a single day in which he missed three catches in the outfield “showed me I wasn’t going to the Dodgers.”

He rarely went to games because “we couldn’t afford it.”

“I had a godmother in Philly, though, where the Athletics and the Phillies played at Shibe Park. I’d stay with her, and she lived so close to the stadium that I had a little business selling tickets for parking spaces. The house was close, but so far. But when I was about nine, a family friend took me to see Jackie Robinson play. That was the one and only time I saw him.

“I thought: ‘There is Jackie Robinson.’ I looked at his stomach and thought: ‘He’s not trim and fast and sleek as he once was. He’s gained weight.’ I said that to myself, in my fresh, youthful way of observing things.” Beckham says he grew up with Jewish school friends, one in particular, and grew aware of the city’s Jewish community partly through female relatives who worked in Jewish homes.

He entered Brown as one of eight Black freshmen in the Class of 1966. There, his reading became a more focused passion. He met Edwin Honig, a poet, translator of Spanish and Portuguese whose intellectual life was fed in part by his family’s Sephardic roots.

Honig, who wrote Dark Conceit: The Making of Allegory, a pioneering book examining the uses of allegory in literature, persuaded Beckham to attend a campus reading by Amiri Baraka, who was then known as LeRoi Jones.

Beckham, who has written an essay about his passion for getting other writers’ autographs, got Baraka’s in his copy of the writer’s only novel, The System of Dante’s Hell.

Beckham took a writing workshop with John Hawkes, one of the most highly regarded, experimental novelists to emerge after World War II, and a nurturer of young writers.

Hawkes was known for his wide range of narrative approaches. He was “committed to nightmare, violence, meaningful distortion,” he once told an interviewer.

“Hawkes gave me the sense of freedom, that you could do anything in fiction. The only limits are those of your imagination. He gave me the gift of encouraging me to follow a story where it led.”

In an essay published by the Brown Alumni Magazine in 1970, the year Beckham began Runner Mack, he described his time with Hawkes in terms of baseball, comparing his feeling for Hawkes to a baseball player’s admiration for Jackie Robinson.

For Hawkes’ class, he made a strong start on what he felt would be a novel, the beginning of My Main Mother, but the writing went flat, and Beckham lost confidence in his instincts. Midway through Brown, after a high school girlfriend became pregnant, he married her, and had a baby son by the time he graduated.

He took his languishing work-in-progress to New York, where he’d been admitted with a full scholarship to Columbia Law School. He left Columbia after six weeks — “I did not like it,” he said. The short time ended with an exchange he recalls with clear anger.

“When I told the person I was leaving, he didn’t make the slightest effort to talk to me about it, to understand it, to keep me there. And why do you think that is?”

“Because you were Black,” I said.

“That’s right. It is something, isn’t it? Not a question. No effort to talk me out of it.”

Though he was set on finishing My Main Mother, he had to support his family so he took a job at Chase Manhattan Bank and wrote in his hours outside the office. Chase’s offices, near Wall Street, helped inspire the office spaces in Runner Mack‚ vertigo-inducing corridors and other areas that Henry Adams perceives as being full of racist pressures and menace.

Kafka, who specialized in making workplaces threatening, was as an insurance lawyer, a regulator at an agency that shaped oversight of workplace conditions, reaching a professional level rare for Jews in broadly antisemitic Czech society.

Chase had started the first urban affairs department of any bank in America.

For Kafka, the real-life understandings he gained came in the factories and farms of Prague.

For Beckham, they came at a special school Chase was developing in Harlem.

An education in Harlem

In 1964, during the summer between Beckham’s sophomore and junior years at Brown, a 15-year-old named James Powell, who was Black, was shot and killed in Harlem by a white police lieutenant named Thomas Gilligan in front of Powell’s friends and about a dozen other witnesses.

The shooting set off six straight nights of rioting that engulfed Harlem and other Black neighborhoods. Police were attacked, protesters were severely beaten. One rioter died, 118 were injured and 465 were arrested.

Hundreds of shops were looted, and damages ran in the millions. That September, Gilligan was cleared of any wrongdoing by a grand-jury and charges were dropped. He always maintained that Powell attacked him with a knife.

White-run institutions, under pressure to demonstrate their understanding of how dire conditions had become, began to respond with new social programs and cultural projects to stop the riots from recurring. They were funded in certain cases by President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs.

Thousands of young people were employed.

The riots spurred Eugene S. Callender, an influential Harlem pastor and civil rights activist, to set up what he described as a “competitive school system to expose the deficiencies in the school system by equipping drop-outs for college.”

There would ultimately be 14 of the academies in Harlem and other boroughs, located mostly in storefronts, run by administrators who combined a familiarity with the streets and an educational background.

The New York Urban League, the long-time non-profit for social programs in the city, oversaw the academies. Several major corporations, including Celanese Corporation, Pan Am and American Express, provided funding for them.

Chase sponsored an academy near 148th Street in Harlem: The Chase Manhattan Street Academy.

Beckham was named Chase’s representative to the academy, monitoring its budget and management.

One winter day in 1967, a 23-year-old Barry Beckham rode the Chase elevator down from his private office on the 35th floor, boarded the subway to 145th Street and Seventh Avenue, and soon walked into another kind of education.

Waiting for him was Dennis J. Watson, who towered over the 5-foot-6 Beckham. Watson, the academy’s administrator whom Beckham recalls as being “charismatic,” stood inside the door laughing at the new arrival who looked out of place in his blue banker’s suit at a school for kids in deprived neighborhoods.

“Barry comes in wearing a navy coat with gold buttons,” said Jacquie Kay, who was then in charge of teaching at the academy and went on to do graduate work in education planning at Harvard.

Watson, Kay said, looked him up and down and declared: ‘Whoa! You are some dresser!’

“Hey, I look so cool because I got this from the Salvation Army for like 11 bucks!” Beckham told him.

That broke the ice, and Beckham and Watson became friends.

Though they had arrived at that store front from different worlds —Watson had grown up in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn and became a standout high school basketball player — both were passionate readers who liked to talk about what they read, which included Kafka, Sartre and other existentialist writers. “Barry had come of age as a Black person in America,” Kay said. “But he retained — how should I put it? — certain illusions about the possibilities of advancing high into corporate power. Dennis questioned those corporate ambitions.”

“I was sure I was going all the way to the top,” Beckham told me, with an ironic, sideways smile, recalling how Watson urged him to question the American Dream more deeply.

And just being with Watson shed light on urban realities that were never as real to him before. They were driving through Harlem when Watson stopped to pick up a friend, who pointed to a corner where he said police had killed his friend.

The banker-writer saw police violence more clearly than he had in Atlantic City.

“Dennis radicalized me,” Beckham stated.

A genius at characterization

The year he started at the academy, he enrolled in a writing workshop at New York University, run by a writer named Sidney Offit, the son of a Jewish bookmaker in Baltimore who became a writer and well-known figure in the literary circles of New York during the 1960s.

I saw a painting of Offit, now 96, hanging on the first floor of the Century Club, the prestigious, midtown Manhattan haven for writers and artists when a member invited me there for lunch not long ago. In the painting, Offit looked sophisticated but streetwise, a loose flap of pale boyish hair cutting above a chiseled face.

Offit told me two of the best moments of his life were when Kurt Vonnegut called him his best friend and when he met Barry Beckham.

The first night Beckham attended a writing workshop he ran at NYU in 1967, Offit was so impressed he was “ecstatic.” The glow of Offit’s enthusiasm turned Beckham’s creative malaise into a wonderful ease with which he finished the rest of My Main Mother.

“He had a character (in Mitchell Mibbs), who was so genuine,” Offit told me. “He captured the human being. He is a genius at characterization and creating individual personalities.

“He had the individual voice,” he added, saying, “There was a humor to it, at the same time, a stunning reality. I recommended it to an editor friend of mine. The response was instant.”

That friend was Ed Burlingame, editor-in-chief at Walker, and one of the more respected young editors in New York publishing.

“I was just struck by the originality and the promise of this young creative writer,” Burlingame, now in his 80s, recalled, of first seeing Beckham’s manuscript. “I wanted to take a chance on him.”

“Publishing was a white industry, but I published other writers of color,” Burlingame said. ”We needed to hear more from and about young Blacks and young Black men. But that wasn’t why I published Barry’s novel. I published it because it was original and he could write.”

My Main Mother appeared in January of 1969 to reviews that praised the novel’s inventiveness and narrative quality and repeatedly described Beckham as a writer of unmistakable promise.

A few months later, Beckham wrote “Being Black at Brown,” an article for Esquire magazine that explored Black Ivy League students’ alienation and future prospects.

He took readers on a Black professional’s path through “high school, college, business.” “In each instance,” he wrote, “it is the Black man thrust upon the scene, bewildered, unfamiliar, abashed, like some character from Kafka floundering in his castle.”

Around that time, Beckham started to keep a diary. In it, he wrote of being inspired by watching Dr. Strangelove, which satirized the absurdity of nuclear war.

“[Peter] Sellers is tremendous, especially as Dr. Strangelove and the message is potent,” Beckham noted. “I think more and more about my great novel concerning the dissolution and wrongly directed priorities of this country.”

America in torment

In the late 1960s, America seemed to be dissolving amid jolting events that seemed almost unreal. Vietnam persisted. There were assassinations, protests, riots; old forms of control gave way to chaos, a dizzy whirl of a changing yet changeless world in which social divides stayed intact.

“The promises of the Great Society have been shot down on the battlefields of Vietnam,” Martin Luther King, Jr. told an audience.

Not long afterward, on April 4, 1968, King was murdered.

From Columbia on the East Coast to the University of California at Berkeley, university students erupted with anti-Vietnam protests and broad, anti-establishment anger. African Americans, who had been held back by oppressive academic limitations that mirrored the construct of the society as a whole, agitated for changes in what was taught, who did the teaching, and the need to make admissions a fair and equal process.

From New York, Beckham watched with interest as a new generation of students at Brown, far more activist than he and his generation, formed the Afro-American Society (AAS).

The AAS gathered data showing that between 2 and 3% of Brown students identified as Black. On Dec. 5, 1968, three-quarters of Brown’s African American students walked off campus to press their demands for more Black students, more Black professors and courses focusing on African American culture and history.

One of the professors who supported their cause was Charles Nichols, a much-liked Black Quaker who had taught at a university in Germany and whose courses at Brown focused on both Black literature and the literature of the Holocaust. After he became head of the university’s new African American studies program, he read My Main Mother and was so impressed he wrote to Beckham, inviting him to teach at Brown. Beckham taught literature and also became the first Black professor of fiction writing at the university, where he remained for 17 years, two of them as director of the writing program.

“I was only 24 and I only had a bachelor’s degree,” Beckham told me. “But I was hired because of the students’ demands, with which I was familiar because I was very aware of what was happening at Brown. It was an historical moment. I didn’t take part directly. But I was aware.”

Wokeness sets the stage

The campus of Brown and the city of Providence are closely interwoven. The city is compact and busily urban, making the walk onto the center of campus itself a fluid shift in the mind between urban landscape and academic refuge.

The house Beckham rented when he returned in 1970 was a quaint but sturdy-looking three-story wooden one with a generous porch on Irving Avenue, on a hillside in the city’s College Hill neighborhood.

There, Beckham began to shape a new course on African American protest literature, whose readings would consist of work by and about the Black Panthers, the Nation of Islam, Eldridge Cleaver, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the group of young activists who put the ideals of the Civil Rights Movement into practice.

To prepare, he read works he would teach “more carefully myself than I had done before,” he told me.

The class, he recalled, was “about half Black, half white,” and the questions he addressed included how leaders for change developed and the relationships they built with the people they attracted. What was it like to stand up to oppression for someone who had not done so before?

And Beckham kept thinking about these questions as a writer: “How could I not be thinking, as I walked through campus: ‘How can I put this into my fiction? What kind of fiction would it be?’”

Beckham also taught the work of the Black Nationalist Marcus Garvey, who in the 1920s forged a national movement that inspired Black Americans to stand up against a lack of basic rights.

George Bass, a New York theater figure who had founded the Rites and Reasons Theatre, devoted to theater by and about African Americans, suggested Beckham him a play. Beckham created an intimate, cabaret-like work about Garvey.

“Garvey Lives!” — it had just one production — ends after Garvey dies in exile in Jamaica, and a female follower declares: “I been sleeping all my life. And now Mr. Garvey done woke me up. I’m gon stay woke. And I’m gon help him wake up other black folk. Garvey lives!”

Beckham also started a new novel about a baseball player.

He isn’t sure which he started first, his play or Runner Mack.

Writing ‘Runner Mack‘

In 1970, when Beckham started his baseball novel, Jackie Robinson had been retired for 14 years. Larry Doby, the second African American player who’d integrated the American League, had been done playing for 11.

That year, 14.6% of major league players were African-American. 11.7% were Latino, and 73.7% were white. Beckham began a counter-factual story about the statistics-obsessed game, setting aside the self-congratulatory myth that white America had made of Black players’ admission to the national game.

Baseball progress came amid ongoing racial adversities and belligerences, including the professional inclusion in many fields beyond sports achieved by a few, denied to many.

Beckham had read The Natural, knew Malamud’s use of Arthurian legend, admired its craft, but followed an approach he terms, “Kafkaish, Hawkesish, Ellisonish.”

One possible source for using baseball as a fortress Henry Adams could not enter, Beckham says, was his childhood wish to do more than park cars for others heading to the stadium near his Philadelphia relatives. He remembered sitting in front of the house, hearing “people talk about baseball games I couldn’t go to.”

He loaded his hero’s name, Henry Adams, with a two-sided meaning. One side belonged to Henry Brooks Adams, a descendant of two presidents and the writer of The Education of Henry Adams, a memoir regarded as an American classic. That Henry Adams was also a devoted white supremacist and antisemite.

Another Henry Adams who Beckham had in mind was a post-Civil War Black nationalist and voting rights activist from Louisiana who also had that name. Referring to both, Beckham made Henry Adams into a vessel for questioning how much Black lives mattered in American democracy.

Beckham’s editor at William Morrow and Company, his publisher for the book, was Phil W. Petrie, one of the few Black editors in the publishing industry at the time. Petrie also edited Nikki Giovanni, the poet and activist.

How fully the writing of Runner Mack absorbed Beckham, as he worked in Providence, became clear when Petrie phoned him one Sunday afternoon.

“He asked where I was with this novel, and I said, ‘I’m in Alaska,’ and he called to his wife with astonishment: ‘Barry’s in Alaska!’ And I never forgot that moment,” Beckham recalled.

Literary detectives sometimes dig into mysterious sources for the main characters in books they admire. But Beckham makes no secret of the friend he turned to when he was writing about the revolutionary Runner Mack, who enlists Henry Adams in his plan to blow up the White House.

It was Dennis Watson from the Chase Academy, urging him to shed his illusions about climbing the corporate ladder, whom he transposed into the man who opens Henry’s mind: Runnington “Runner” Mack.

Conversations Beckham had with Watson, to whom he would dedicate his book, inspired the dialogue in which Runner Mack urges Henry Adams to abandon his baseball dreams and turn to revolution.

“Everything’s all set, huh? How much bread they given’ you?” Runner asks.

“Well, everything’s not really set yet,” Henry replies.

“They don’t want to give you a play,” Runner tells him. “Seen it happen a million times. Same ol’ same ol’. It’s our history. Can’t you see?”

“Well, hell, my man,” Runner concludes, “You’d better wake up.”

After Henry signs on to Runner’s planned White House attack, they return to the city where Henry’s story began. When Henry visits Beatrice, the wife he’d left, she’s gone deaf from the city’s noise — disabled by societal traumas, one senses. She can’t hear Henry when he tells her where he’s been.

Runner Mack has high hopes for a mass gathering he will lead, but he and Henry are stunned when only five people show up. “History keeps going and we keep trying and nothing happens,” Runner says.

What has happened? Did Runner fail to inspire? Did people fail to be inspired? Beckham doesn’t say. In that void, Henry searches for a Runner Mack who has suddenly vanished. He finds him swinging behind the door of a bathroom stall, a suicide, which sends a shocked Henry running into the streets.

The last image is of the Mack truck, “bearing down on him” with “the mouth of a fender smiling at him.”

Beckham’s Garvey lives, after he dies, through others.

Henry Adams outlives Runner Mack, woke but terrified.

Hard times

Most reviews of Beckham’s first novel that had been published three years earlier were written by white critics, including a piece in The New York Times by a British freelancer who’d written books about aristocratic country estates. He lauded Beckham as a writer of promise but showed little interest in the work as a picture of the Black experience.

The Sept. 17, 1972 Times review of Runner Mack was written by Mel Watkins, who noted the Kafka connection as well as nuances that might easily have escaped a white reader. He wrote of how Beckham created a fictional experience for Henry Adams that “parallels black history from slave ship to the present emergence of militant revolutionaries.” Certain episodes, Watson wrote, “are representative of Blacks’ plight on slave ships and the auction block, and a panicked stress in a subway ride is meant to suggest the Underground Railroad.”

“He knew about the experiences from which I drew the book, and he was able to write about the novel by connecting to his experience as Black person,” Beckham said of Watkins’ review. “That mattered a lot to me.”

It is hard now to recall how exceptional it was for a long-time Black critic to review the work of a Black writer in a major American newspaper.

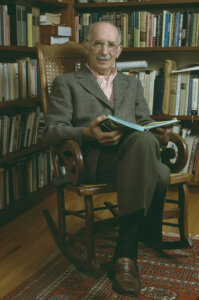

I met the tall, lanky Watkins, now 83, at The Tavern on Jane, a bar with exposed brick and dark wood in Greenwich Village.

Before Watkins retired from the Times in 1985, he had a 20-year career there as a book critic. In 1966, he became the first Black editor for The New York Times‘ Sunday Book Review, working as both an editor and a critic. He counted Toni Morrison, James Baldwin and other writers among his friends, and became part-owner of Boomers, a West Village bar that opened in 1969. Miles Davis, Nina Simone, poets and playwrights who identified with the Black Arts Movement, members of the Negro Ensemble Company, mingled and listened to jazz by leading artists. Scenes from Super Fly, the 1972 fantasy of urban defiance and coolness, were filmed there. “It was a fun time,” said Watkins matter-of-factly.

Runner Mack, he told me, was “probably the most outstanding among the five or six best novels of that time, almost as strong as Ellison, not quite, but almost.”

Watkins does not know of another Black writer who related to Kafka as fully as Beckham, he said, adding: “It has always bewildered me that more African-American writers have not sought inspiration in the work of Existentialists, especially the work of Kafka. What Beckham did was unique.”

But Runner Mack sold poorly, only 15,000 copies, according to reports Beckham keeps.

The number, Watkins believes, shows how the novel turned a mirror on society that white Americans didn’t want to see. “I think the mainstream avoided Runner Mack because it made clear there was systemic racism,” he said. “It showed what the country was really like.“

Watkins told me that he’d wanted to play pro baseball and had tried out for the Detroit Tigers. After his try-out, he approached a white Tiger player he admired, to shake his hand. The player rebuffed him, a snub Watkins is sure was racist.

He wrote about that moment in Dancing with Strangers, his memoir of growing up in Youngstown, Ohio, as a teenage athlete and intellectual reading Kafka and other modernists.

“In the ’60s and ’70s, people were just beginning to get enough education to appreciate a book like Beckham’s,” Watkins told me. “That was a big part of it, and it affected other books that should have done better.”

In a 1983 reprint of Runner Mack by the Howard University Press, Watkins wrote an introductory essay that drew comparisons and contrasts between the novel and the writing of Kafka and Ralph Ellison, calling Beckham “among the few black American writers to put aside naturalism and successfully venture into the genre of satire and surrealism.”

For Black readers, Watkins believes, the reality-bending tendencies of Ellison and Beckham posed a challenge that was a turnoff because they turned toward naturalistic works about African-American life. Beckham’s sensibility was “never likely to reach a wide audience,” he said.

Watkins and I talked about Beckham’s problems finding mainstream publishers for his later work and how that difficulty had contributed to a severe depression.

Watkins referred me to his 1981 Times piece, “Hard Times for Black Writers,” in which he reported a “drastic shift in the situation of Black writers” that happened in the early 1970s.

After the 1960s and what had appeared to be “a second Negro renaissance in literature,” there was a sharp drop in the number of Black senior editors working for major publishing houses, and the situation reversed to one where “some publishers” believed “the mere inclusion of the word “Black” in a book’s title hurts its chances.”

Nearing 80, Beckham still fills orders for books from Beckham Publications, which he founded while still teaching at Brown. He keeps his own works available after reclaiming the rights when their first publishers let them drop out of print. For years, he’s published widely used college guides for Black students.

Beckham Publications offers Double Dunk, a work he wrote after Runner Mack — one that he said was rejected by a New York publisher. It reaches into the inner life of an actual Black athlete, Earl “The Goat” Manigault, a legendary street basketball player from Harlem whose promise gave way to heroin addiction.

The novel Will You Be Mine concerns a Black photojournalist in Washington, D.C., who covers civil rights stories and falls deeply in love with a dying woman. Currently, Beckham says, he’s working slowly on a longtime project of writing about his time at Chase, while taking notes for a planned book of short stories about racial murders, including that of Emmett Till.

He imagines turning the house where Till’s late mother, Mamie Till, lived on Chicago’s South Side into a fictional space that would work like a magnet, attracting the voices of characters who had been part of the killing and the trial at which Till’s killers were acquitted.

Back to those familiar faces

The last time I spoke with Beckham, we talked about getting together again at the Trattoria Dell’Arte one day, when his back improves and he can walk with more certainty.

I recently went back on my own to enjoy the memory of our meeting. I toured the portraits of the writers on the walls: Pavese, Ungaretti, and Giuseppe de Lampedusa, known for The Leopard, his single melancholy novel about an aristocratic family in the grip of historical change.

Pirandello looked down from the wall above the table in that corner, and I thought about the way he portrayed the shifting relationship between reality and imagination.

Most, before they died, had probably read Kafka. Few, I decided, knew much about a baseball diamond or the tough realities of who got to run around one and who didn’t. Each has found a place among writers of modern classics for works that comprehended their country in singularly significant ways.

So, I thought, should Barry Beckham.