First PersonOur Passover: Why this night is different from all others

How non-observant Jews passed on their love of Jewish traditions to their daughter and half-Jewish grandsons

“The rituals can transform according to who is sitting at the table. The vital thing is to keep sitting there.” Courtesy of Elissa Caterfino Mandel

It wasn’t until my half-Jewish sons were in preschool at the JCC that my family celebrated Passover with a haggadah. It was a Xeroxed version with large print, and my boys passed it around the table gleefully, especially when we got to the plagues. Our service lasted less than eight minutes.

The only questions we asked at my childhood Seders were whether the gefilte fish was sweet or salty. Even without the Ma Nishtana, my mother made a beautiful Seder. Her treasured 1970s green Seder plate still sits in my dining room buffet. We never dipped anything into salt water, but my mom did have other rules for Seder.

“Shank bones go fast, so get to the market early,” she said. “The best greens for the Seder plate are romaine. Use the extra for the fish; a little lettuce can make even gefilte fish look important.”

At our Passover table, the exodus of the Jews rarely came up. We spoke about gas rationing, the Iran-Contra scandal, and, before he was controversial, Philip Roth and Zuckerman Unbound. Growing up in the Midwood and Flatbush neighborhoods of Brooklyn in the 1940s and ’50s, my mom and dad came from families that were proud members of the tribe but never the congregation.

In the Levin Sagner development we moved into in 1968, my parents socialized with other Jews. They rooted for Brooklyn Jewish icons like Sandy Koufax and those who had chosen to be Jewish icons like Sammy Davis Jr. But in our house, we only lit candles when the electricity was out. And although they joined the JCC (then known as the YMHA, or Young Men’s Hebrew Association), my parents never became members of one of the five Reform congregations that were less than 10 minutes from our house.

I was probably the only kid in the tri-state area who lobbied to go to Hebrew School. After taking me on a tour of a reform synagogue in not-so-nearby Cedar Grove, my mother nixed the whole thing.

“You work hard enough in school. I don’t want you to have the pressure of Hebrew School too,” she said.

Although my sister always dated Jewish men, it never occurred to me to do so. I met my future husband Doug my sophomore year of college. He was a lapsed altar boy who’d never had a bagel except out of a Lender’s package. “He will never eat gefilte fish,” my mother predicted correctly.

Fortunately, Doug loved big family meals and his family practiced religion the same way mine did — through cultural touchstones and food. He’d grown up eating and loving gravy — which my family called tomato sauce — at his Italian grandparents’ house every Sunday. One Christmas Eve after dinner with my future in-laws, Doug and I ran out to see Out of Africa. Turns out my parents were doing the same thing.

When we became engaged in 1987, there were few rabbis willing to preside over a “mixed marriage.” We were married by a local judge. Doug had one request for me: If we raised our children Jewish, we had to have a Christmas tree in our home. We did, and we never had a bris. Both Doug and my father agreed the ritual was barbaric.

Searching for a community, Doug and I tried out a few temples and ended up with one seven minutes from our house. My parents joined us at our temple’s children’s services and registered the delight on my boys’ faces when they heard the noisy novelty of the shofar. My mom and dad became comfortable as guests at our temple and discovered that the sermons were often topical and interesting. At one point my dad said, “I think your rabbi should memorialize us when we die.”

Unfortunately, Doug died before my parents did. He passed away from a brain tumor in 2001, when our sons were 7 and almost 10. Until that year, my parents, sister and I had never gathered together to say Kaddish. I stood numb with grief with my prayer book and my sons, parents, in-laws and what felt like an entire community of friends and relatives.

After Doug’s death, my parents became even more active as grandparents than they had been before, proudly standing at the bima for both my boys’ b’nai mitzvah.

My dad and mom died this past year, four months apart. As I promised my dad, the rabbi he had loved, Rabbi Dan, led both services. For my mother, final goodbyes were complicated. At 86 after multiple mini-strokes, she had lost the ability to make her wishes known, but I knew she loved Rabbi Dan. When she saw pictures of the yarmulkes at my older son’s wedding, where Rabbi Dan officiated, she put her finger up to the cellphone, touched the picture, and murmured the single word she was still able to say, “Beautiful.”

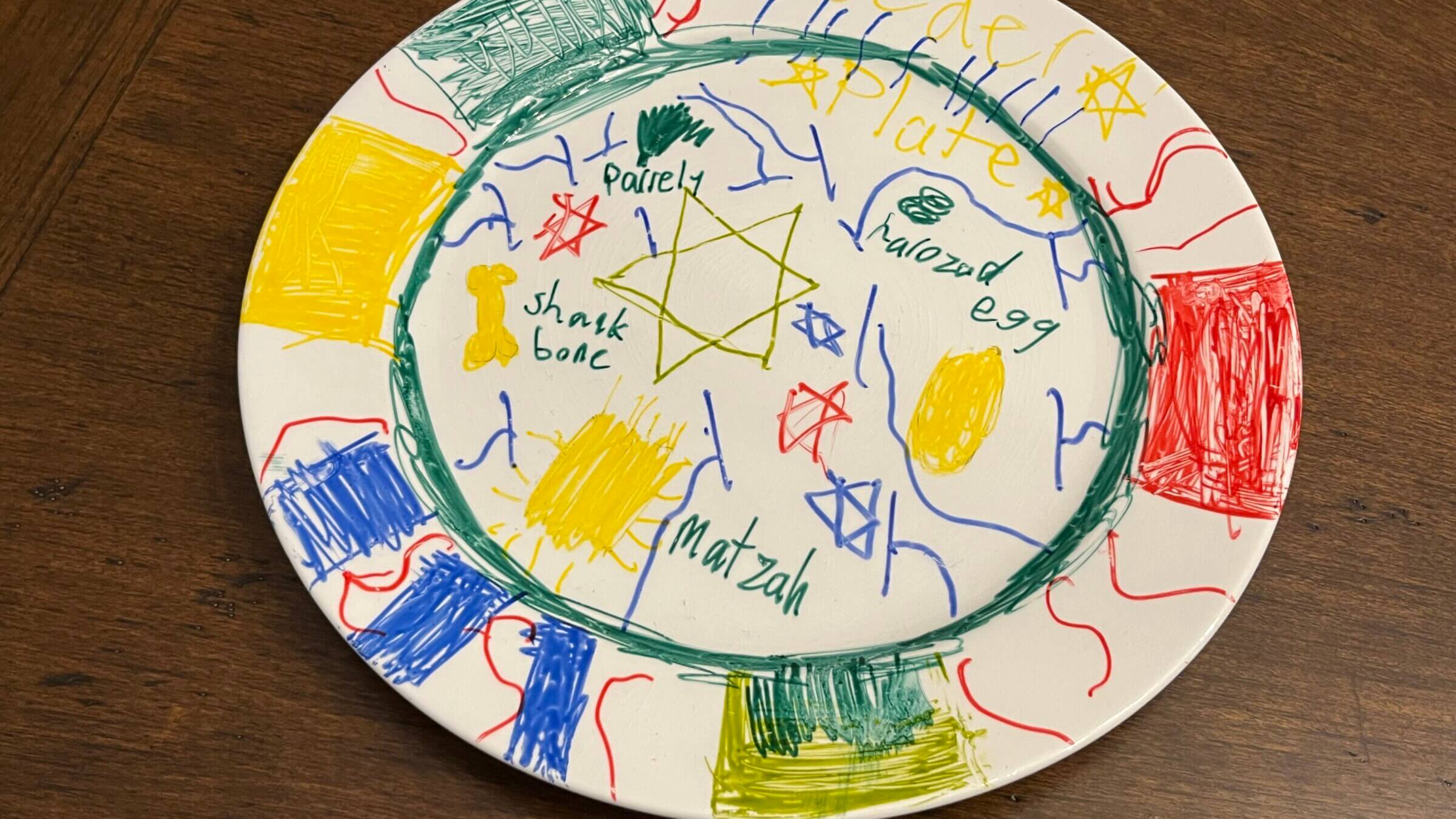

As I come out of my mother’s period of shloshim, a word I didn’t know in childhood, I think about the Seder table I will soon set. The green Seder plate will be there, and so will my older son’s preschool afikomen cover with his tiny blue handprint from 1995. Most of the people who filled the chairs at our brief Haggadah reading 21 years ago are gone. Our Seders are longer now. My second husband can read every line of Hebrew in our family Haggadah while my non-Jewish daughter-in-law reads the English like I do. My parents understood something I have come to appreciate — the rituals can transform according to who is sitting at the table. The vital thing is to keep sitting there.