A methuselah of Chardonnay? A solomon of Champagne? How big wine bottles got so biblical

Why are large-format wine sizes all named after kings from the bible?

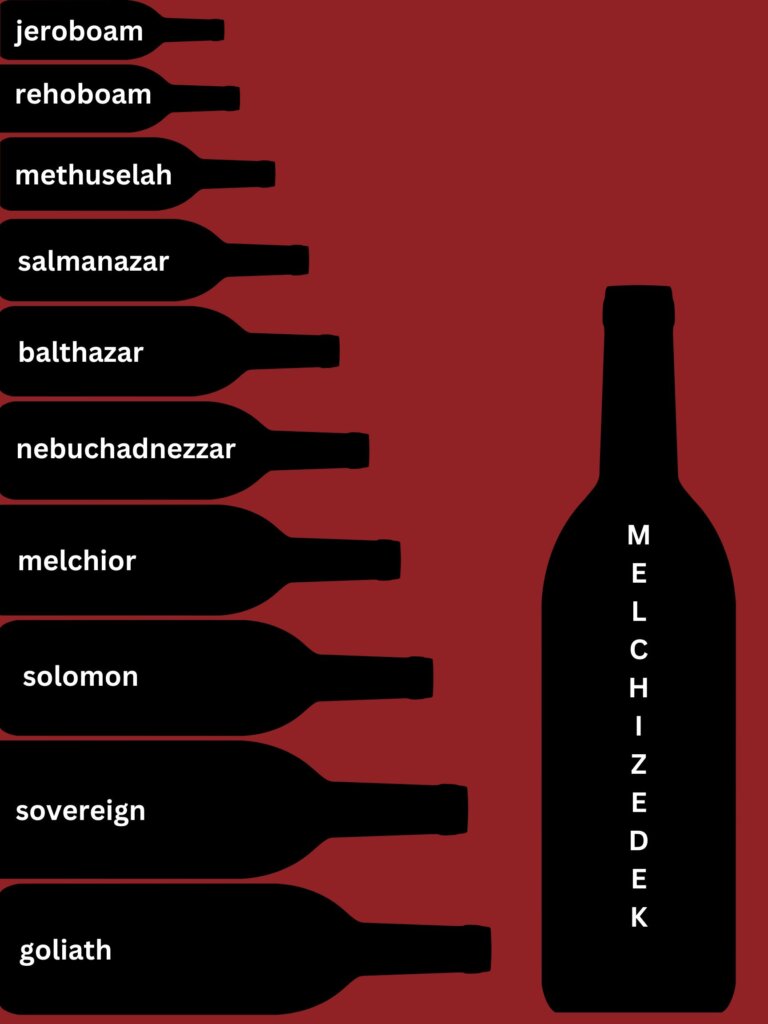

The kings behind the wines. Graphic by Mira Fox

Perhaps you’ve already purchased some magnums of Manischewitz for your Seder table this Passover. But wouldn’t it be more efficient — and thematically appropriate — to set the table with a methuselah or a nebuchadnezzar?

If you’re confused, allow me to enlighten you: Methuselah and Nebuchadnezzar, in addition to being biblical figures, are sizes of wine bottles. Big ones. “Large-format,” as they’re called in the business; they hold 8x and 20x the size of a regular bottle, respectively. Sure, they may not be practical — it’s hard to imagine pouring from a nebuchadnezzar — but they’ll certainly serve your whole Seder table.

Wine bottle sizes, at least according to industry publication Wine Enthusiast, range from a split or piccolo, which holds just one glass of wine, all the way up to that melchizedek, which holds a whopping 200 glasses of wine, or 40 standard bottles, with biblical kings and other figures naming each size from jeroboam on up.

The biblical naming begins only after the magnum; below that, sizes have uninspiring names like “standard” and “liter.” So what led to the grandiose, ancient kingly names given to the large bottles?

The names behind the sizes

It’s probably a good idea to start by listing the sizes, and who they all are in the bible. Some of these sizes have other names — the melchizedek is also known as a midas, for example — but for the sake of simplicity, I’m leaving those out. There’s enough kings to keep track of as it is.

Jeroboam (four bottles of wine): After the death of King Solomon, Jeroboam led the northern kingdoms of Israel in revolt; they formed their own kingdom, with Jeroboam as their king. He built a bunch of golden calves to worship, so not exactly a godly guy.

Rehoboam (six bottles): One of Solomon’s sons and his royal successor. Rehoboam ruled the southern half of Israel after Jeroboam’s secession, and waged a lot of war in an attempt to reunite Israel.

Methuselah (eight bottles): Most famed for having the longest lifespan in the bible — he lived to 970 — Methuselah was the grandfather of Noah. While he appears in some extratextual sources, in the bible, his mentions are basically limited to genealogies.

Salmanazar (12 bottles): This one is a bit tricky — there were five kings of Assyria with this name, beginning in the 1200s B.C.E. Salmanazar V appears in the bible as the conqueror of Samaria in 2 Kings.

Balthazar (16 bottles): Maybe one of the Three Kings who visited the infant Jesus in the New Testament — the one who brought myrrh, to be specific. But the name isn’t given in the Gospel of Matthew, and was settled on later by the Western church, which also tends to portray him as a Black man.

Nebuchadnezzar (20 bottles): Nebuchadnezzar the Great — or, to Jews, “destroyer of nations” — was one of the most powerful kings of Babylonia. He built the famed Hanging Gardens, one of the lost Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but also conquered and destroyed Jerusalem.

Melchior (24 bottles): He’s another one of the Magi — the one who brought gold. Also maybe the King of Persia? Like Balthazar, his name is not actually given in the bible.

Solomon (26 bottles): I think we all know about King Solomon. He had all the wives, and was maybe a prophet, and built the First Temple. A big deal all around.

Sovereign (35 bottles): This is just a synonym for “monarch.” But it’s a big jump in size, so there’s that.

Goliath (36 bottles): Famed for being killed by the not-yet-king David with a slingshot, he was a really large Philistine warrior.

Melchizedek (40 bottles): Melchizedek is first mentioned in Genesis, when he blesses Abram, who will become Abraham. He is also the first person to be identified in the Torah as a priest, and the name has historically been associated with mysticism and high priesthood.

I’m sorry, who needs a wine bottle that big?

The short answer is: nobody, really. You can’t lift most of them on your own, let alone pour. The point is marketing and, of course, bragging rights.

“These big bottles are really very, very rare,” said Rod Phillips, a wine judge and professor of history at Carleton University in Ontario. “They’re really only done for publicity or for special events to draw attention to something.”

The sovereign size, for example, was made to christen the Sovereign of the Seas, a giant cruise ship, in 1988. As far as Phillips knows, that’s the only time a sovereign bottle has ever been made. Similarly, he said, a 130 liter bottle was made by Beringer, a California winemaker, in 2001, and sold at auction for “a huge amount of money.”

“Things like that are just curiosities,” Phillips said. “No one is going to come to a dinner party with a 130 liter bottle of wine.” (Phillips has, however, brought a jeroboam to a birthday dinner, though just once. “I think there were about 12 or 15 people there for dinner and I came and I said, I’m sorry I only brought one bottle,” he said. “It’s a great line.”)

But the smaller large format bottles are actually produced — not regularly, exactly, but they exist. You probably can’t waltz into your local wine store and grab one, but you can special order them.

This is for two reasons. One is that wine is thought to age better in larger bottles, so if you’re buying wine to age, a magnum or even a jeroboam is a good choice. For sizes past that, the reason they exist is just, well, Champagne — which is what they almost always contain.

“Champagne has always been over the top. It’s a very successful brand, Champagne, because they marketed themselves right from the get-go as a special wine for special occasions,” Phillips said. “Anything that’s very much a celebration is for Champagne, so big bottles suit Champagne. A bigger bottle means a bigger celebration.”

But why biblical kings?

I searched high and low for an answer to this question, and there are a lot of theories. Some posit that the jeroboam size — also known as a double magnum — grew out of an old English term, “jorum,” which referred to a large drinking bowl that was passed around the table. That could connect to the biblical character of Joram, whose father gave King David expensive drinking vessels, and that somehow free-associated its way to jeroboam and the rest of the kingly names followed from there.

The Oxford English Dictionary, meanwhile, traces the use of “jeroboam” back to the writings of Sir Walter Scott in 1810 (he wrote of making a “brandy jeroboam,” though I have to assume he wasn’t drinking three liters of brandy) and conjectures that the term is connected to the fact that Jeroboam caused Israel to sin. Just as drunkenness causes many people to sin, I guess.

Or, there’s the idea that, since the biblical Methuselah is famous for his age, “methuselah” seemed like an apt name for a large bottle of wine for aging, and the rest followed from there. Some of the other names also have loose associations with drinking or vessels, emphasis on the loose.

These all seem like a stretch, of course, and no one has any definitive answer. “My sense is this: Somebody, whoever came up with these conventions — we really don’t know — wanted to give wine a kind of royal or aristocratic association,” Phillips said. “If you say Napoleon you upset the Brits. And if you say Churchill, you upset the French. And if you say Lincoln, people think of a car. So you go back to the bible.”

Much of wine history happened sort of by happenstance, like this; even the standard wine bottle is sort of a strange size.

There are many theories for why the wine bottle is less than a liter, but one of the more convincing, Phillips said, is that wine bottles had to be hand-blown. And people suppose that the average breath of a professional glass-blower expanded the glass bulb to about the capacity of a standard bottle. Large-format wine bottles couldn’t be made until a machining process was developed for glass bottles, in the 1800s.

Even the standard bottle wasn’t possible until the 1600s, when an English eccentric, Sir Kenelm Digby, developed a new glass-blowing process that resulted in a stronger bottle. (Digby’s other inventions, including a “powder of sympathy” that supposedly healed wounds by being applied to the weapon that caused them, have not stood the test of time.)

Perhaps the only answerable question here is why the kings and characters whose names grace these bottles are so obscure. Sure, lots of people know about Solomon and even Methuselah, but who has heard of Rehoboam or Salmanazar?

“Wine people are like this,” Phillips said. “They like to be obscure about all kinds of things, make wine more complicated than it really is, and be very clever.” If you have a wine guy in your life, you know that this part of the story, at least, is 100% certain.