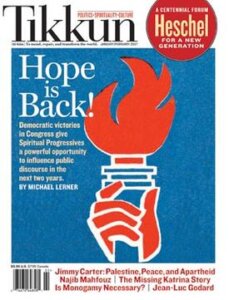

What losing Tikkun means to me — and to the rest of the Jewish world

Founded in 1986, the magazine set itself an unachievable goal — to repair the world

Tikkun founder Michael Lerner son a 2006 episode of ‘Meet the Press.’ Photo by Getty Images

Among the people mourning the closing of Tikkun magazine, I think I am not alone in saying the publication changed my life.

In the 1990s, I was a young academic teaching at University of Kentucky and struggling to write the book that would get me tenure. I was not finding enough meaning in my studies of early 20th century poetry. Instead of writing, I gardened, got involved in the vibrant Jewish community in Lexington KY, and in the course of that, subscribed to Tikkun.

In Tikkun I found the meaning I was missing — the magazine, founded in 1986 by Michael Lerner and his then-wife Nan Fink — was as intellectually rigorous as any academic journal, politically brave, and most of all focused on reconnecting Judaism to contemporary life. When I left academia in 1997 and was looking for a fresh start in my husband’s birthplace, San Francisco, Tikkun’s ad for an editor seemed just the thing. I joined as an assistant editor; within three months I would become managing editor and eventually associate publisher.

Little did I know that 1997 was a particularly rocky time for Tikkun. Michael had left the Bay Area early in the 1990s for New York, the center of intellectual Jewish life. In 1993 he had briefly become a superstar, the “guru” of the Clinton White House. Afterwards, Michael published his two seminal books, Jewish Renewal (1994) and The Politics of Meaning (1996).

Heady with the power of the White House and a bestseller, Michael decided being an editor was not enough and founded an activist organization, the Foundation for Ethics and Meaning. He held one big conference in 1996, then the whole Tikkun organization collapsed. Disavowed by the Clintons, distrusted by intellectuals for the Foundation’s activism and Michael’s starring role in it, accused of writing his own letters to the editor to bolster the magazine’s brand, and, most of all, with the magazine almost out of money, Michael headed back to the Bay Area to try to restart the Tikkun project.

I didn’t know any of that.

When I joined Tikkun late in the summer of 1997, the magazine had just been re-established at New College, a gift of space from Michael’s close friend and thought partner, Peter Gabel. Though Michael had lost some of his cachet, it was not entirely gone. When he asked me to write to luminaries such as Zygmunt Bauman, Yehuda Amichai, Marge Piercy, Arthur Green, Michael Sandel, and Barbara Ehrenreich, they responded. From 1997 to 2002, Tikkun was still the leading magazine for intellectuals interested in both Judaism and politics.

For me, the heart of the Tikkun project was (and remains) the ideas that Michael put forward in Jewish Renewal, The Politics of Meaning, and most of all, in his earliest book, Surplus Powerlessness: The Psychodynamics of Everyday Life (1979). In Surplus Powerlessness, Michael argued that most people feel so beaten down by life that they give up on social transformation. Yet we all yearn for meaning and connection. If and when we find meaning, we are empowered, and will begin the work of social transformation.

Judaism, a religion focused on social justice and on this life rather than the next, made sense to Michael as the perfect vehicle for the kind of meaningful connection that could lead to social transformation. A renewed Judaism, based on the social justice teachings of Abraham Joshua Heschel and the spirituality of Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, would provide the spiritual meaning necessary to power a new politics. Committed to this renewed Judaism, Michael became a rabbi in 1995 and in 1996 began his own synagogue, Beyt Tikkun,which he would later run with his second wife Rabbi Debora Kohn.

As the 1990s turned into the 2000s, however, Michael and the magazine increasingly lost the connection to both Judaism and working class politics. Michael in particular became caught up in a New Age spirituality which eschewed the hard work of religious practice or realpolitik for a utopian hope that “getting in touch” with the divine would lead to a better world. Tikkun lost the New Yorkers and academics who had formerly given the magazine substance.

At the same time, in response to the Second Intifada, Tikkun became increasingly concerned with how best to end the Occupation of the West Bank and Gaza and pushed for a two-state solution. That now is a centrist position in the Jewish world, but back in the early 2000s we were excoriated for being anti-Zionists. Jews left the magazine in droves.

I also was becoming disillusioned with our direction — mainly because, as we lost Jewish readers, Michael began positioning Tikkun as an interfaith magazine of spirituality and politics. For me, Judaism had been central to the project and anchored the spirituality in specific practice. Now, we were publishing other “gurus” and in 2005 Michael started a new activist arm dedicated to what he called “spiritual progressives.” That was it for me.

Tikkun continued, of course, well beyond my tenure. The Network of Spiritual Progressives waxed and waned over these years; the magazine continued to focus on interfaith spirituality. From 2006 to 2019 Michael increasingly berated the progressive left for not “getting” the power of spirituality. His books during this period, The Left Hand of God (2006) and later Revolutionary Love (2019) propound his usual themes of the power of meaning to enact social transformation, but centered their critiques on the stubborn anti-spirituality of the left, instead of the attacks on the economic policies of the right which had marked his earliest books.

In 2009, Michael suffered a bout of cancer. Many of his friends and colleagues suggested he step down and hire an editor-in-chief to replace him. But Michael couldn’t bring himself to leave Tikkun behind — the magazine represented his own journey of meaning from left politics to a Jewish-inflected spirituality. Instead, he worked to rebuild the magazine one more time. Michael hired a series of managing editors including Alana Price and Ari Bloomekatz who brought journalistic know-how, and the magazine grew its readership and regained some momentum. By 2017, however, Michael returned to being the sole editor. By 2019, the print issue had shut down, and the magazine became little more than a blog.

In these last years, from 2017 to 2024, Tikkun was run day-to-day by Cat Zavis, whom Michael had married in 2015. Cat, who also became a rabbi, rejuvenated the Network of Spiritual Progressives and Beyt Tikkun, and Tikkun magazine became a useful repository of manifestos and how-tos for the spiritual progressives of the “NSP.”

Tikkun’s impact will long outlast the magazine. Michael’s books were gestated in its pages; Jewish Renewal and The Politics of Meaning are likely to endure. Tikkun nurtured dozens of writers who went on to bigger pedestals. Outside the Jewish world, sites from Belief.net to Religious Dispatches were inspired and shaped by Tikkun. And Tikkun inspired the creation of an ecosystem of thinkers who cared deeply about progressive politics and Jewish identity. The Jewish Currents that we see today would likely not have been possible without Michael’s insistence that Jewish social justice required a critique of the Occupation. Zeek magazine, which I took over from Jay Michaelson and Dan Friedman in 2006, owed a direct debt to Tikkun.

At Tikkun I learned how to be an editor and a publisher, as I led the magazine through an IRS audit, a distribution bankruptcy, building a nonprofit membership database, and more. I found the calling I had missed as an academic, realizing that I could best use my skills to inform, educate and inspire others through publishing. Most of all, my time at Tikkun solidified the importance of Judaism in my life and my work, even when I was not working in Jewish media. Michael taught me that to live a whole life I would need to integrate a sense of meaning and purpose with my day-to-day, a teaching I have never forgotten.

Michael’s vision, that social transformation is impossible without a personal sense of meaning, continues to resonate today in every story we tell about how people’s sense of loss shapes their politics. Tikkun’s project was ambitious — tikkun olam, to heal the world. The idea comes from the work of a Jewish mystic, Isaac Luria, who believed the world was originally whole until God shattered it, and that it is up to humans to put together the pieces. Tikkun was never going to be able to repair the world, but it gathered some of the missing shards, and that is more than enough to have given this project meaning.