How Franz Kafka can help us understand the history of segregation in America

In Kafka’s work, scholars have found a connection to the Black experience in the 20th century

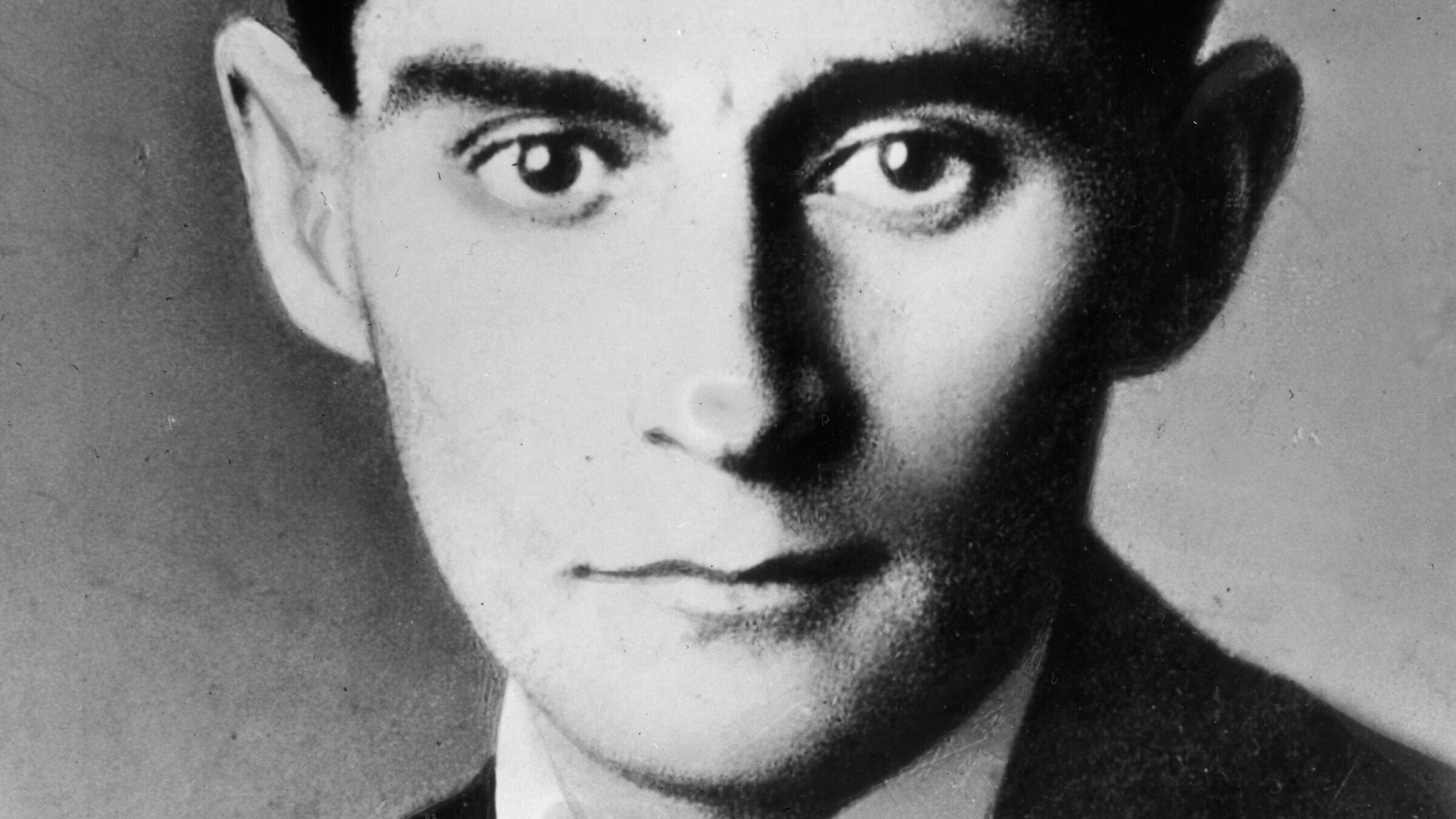

A portrait of Franz Kafka. Photo by Getty Images

Stanley Corngold, a Princeton scholar of German literature, was visiting Jack Greenberg, a Columbia law professor famous for his key role in arguing the Supreme Court’s landmark decision, Brown v. Board of Education. It was 20 years ago, and he was in Greenberg’s Columbia office to discuss an “administrative matter” involving their two universities so sensitive he says “I still can’t reveal it.”

They’d never met, and Corngold, now 90 and a professor emeritus, recalls that Greenberg “suddenly asked me what I was all about. I told him that, at the moment, I was all about Kafka. I told him that Kafka was the in-house lawyer for a Prague institute for workplace compensation, and I was working on a very precise edition of Kafka’s actual office writings. I was stunned when he said: ‘I want to be a part of that!’

“And that,” Corngold told me, “was how we became friends, and taught a seminar together at Columbia Law School called, ‘Kafka and the Law.’ He became a co-editor with me of the book, and wrote his marvelous essay.”

Greenberg’s 16-page essay, “From Kafka to Kafkaesque,” appears in the 2009 book, Franz Kafka: The Office Writings. In it, Greenberg builds a unique bridge between his role in the fight for school integration in America — he was the legal director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund for 23 years — and Kafka’s work as a reform-minded occupational safety attorney. A generation apart, Kafka and Greenberg gained universal views of injustice growing up Jewish in societies where antisemitism was common.

Greenberg, the son of Eastern European immigrants, raised in New York, wrote that Kafka was “one of two Jews employed” by the large Prague Workman’s Accident Insurance Institute, and after diving into Kafka’s work in law and literature, states: “Race comes particularly to mind when we wonder about connecting Kafka with American life today.”

Corngold and I spoke on May 17, the 70th anniversary of the Brown v. Board decision. In its unanimous ruling — stemming from a group of cases, which several civil rights lawyers, Black and white, helped litigate under the guiding force of Thurgood Marshall — the court ruled that state-sanctioned segregation of public schools was unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment. It was a defining moment in American history. In a second ruling, though, the court steered enforcement of the decision in ambiguous language, stating only that public schools must desegregate with “all deliberate speed.”

Those three words helped to create decades of bitter resistance. The Emmett Till murder is recalled as an outcome of that backlash. In 1964, according to Congressional Quarterly Almanac, only 2.14% of Black students attended integrated schools across the 11 former Confederate states. Greenberg bore witness to history he lived by writing about the 20th century’s most powerful voice for the psychic realm where hope meets disillusionment.

The absurdity of a progress that is no progress in The Trial and other writings frames Greenberg’s anger at how the court “wrapped all standards (for enacting the decision) within the oxymoron, ‘all deliberate speed.’”

“‘Deliberate,’ Greenberg writes, “can mean slow. ‘Speed’ connotes fast.”

“A Kafka aficionado would find the impenetrable contradiction delicious,” he observes.

Corngold called me from Cologne on that day when the Brown v. Board anniversary was in the headlines. We talked about how President Biden had made a statement marking the occasion. Then, he revealed he was in the German city to attend a conference marking the 100th anniversary of Kafka’s death at 40 of tuberculosis, on June 3, 1924. This year, on that day, Oxford will be the site of a collective reading of The Metamorphosis, Kafka’s story about a man who awakens one morning to find that he has turned into an insect. In Prague, a Kafka festival will include a series of talks entitled, “Transatlantic Kafka: American and European perspectives on Kafka’s Work.” The program will feature talks by leading scholars from America and Europe.

Unlike many other scholars, Greenberg is not known to have written more about Kafka than his one essay. In fact, I didn’t know it existed until I found it in a more recent work of Kafka scholarship that is just as unusual.

The 2016 book is Kafka’s Blues: Figurations of Racial Blackness in the Construction of an Aesthetic, by Mark Christian Thompson, a professor of English at Johns Hopkins, whose work spans German philosophy and African American literature. The persuasive and fascinating work details an African American scholar’s exploration of Kafka’s seemingly acute awareness of Black life in America during the Jim Crow era.

During months of research for a piece that recently appeared in the Forward about a forgotten African American novelist named Barry Beckham, who wrote a Kafka-inspired baseball novel, I found Kafka’s Blues at Columbia’s Butler Library.

I had searched for other writings that used Kafka as a lens through which to understand the Black experience. Thompson’s work actually explores ideas about Blackness as a path to a deeper understanding of Kafka. It belongs to a trend in which Kafka, the Jewish writer, has become a model for the “post-colonial” consciousness developed by various minorities. (A poem by the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish includes the line: “I found Kafka sleeping beneath my skin.”)

In Thompson’s concluding section, he refers to an essay by one Jack Greenberg — identifying him only by his name, as if he were just a fellow insightful Kafka scholar. Thompson studies how Greenberg’s essay focused on Kafka’s use of the word, Negro, in his unfinished first novel, Amerika.

Kafka never made it to America, but he sent a character named Karl Rossman to New York, and then to Oklahama (sic). Kafka spelled the state’s name the way it appeared in a book about America by a Hungarian Jew named Arthur Holitscher. That book includes a photo of a lynching, which presumably Kafka saw. Kafka’s character, Rossman, when asked to identify himself at one point, just says the word: Negro.

Kafka has him speak the English word, not the German equivalent.

The scene is basic to Greenberg’s essay, the springboard for linking his discussion of Kafka to the battle to end segregation. He writes how Kafka applies the word in other instances, careful to describe the fragmentary nature of Kafka’s unfinished text.

“Karl Rossman’s unhappy travels raise the image of American racial experience, which is in many ways Kafkaesque,” Greenberg writes. “It is likely, of course, that Kafka, personally affected by antisemitism and deeply interested in Zionism, really equated the two groups.”

Thompson takes his study much farther than Greenberg does in Kafka’s Blues, digging for sources of Kafka’s own knowledge of the racial dimension of American life and the layers of his written engagement with it, through Kafka’s fiction, diaries and correspondence.

Greenberg, born the year Kafka died, succumbed to Parkinson’s disease in 2016. Some obituaries mentioned his Kafka essay without hinting at its source. Corngold, meanwhile, keeps writing at a furious pace, including a recently published book of essays, Expeditions to Kafka. He told me that others have looked at Kafka’s use of Blackness, but that he hadn’t heard of a whole book devoted to the subject, or that an African American scholar in Baltimore had given a second life to his old friend’s essay.

He laughed when I told him that Thompson didn’t refer to Greenberg’s biography, beyond saying he had made “important connections to American legal-racial history.”

Thompson wrote as one Kafka thinker responding to another with obvious respect for what he had to offer.

That possibility grew from the visit between two professors 20 years ago that took a turn toward the future neither man could have imagined.

I pressed Corngold again about the matter that had drawn him and Greenberg together.

“I don’t want to be mysterious,” he said. “But it must remain unknown.”

“That,” I noted, “sounds truly Kafkaesque.”

“Absolutely,” the professor said.