What if there was a flag that both Israelis and Palestinians could take pride in flying?

Tom Haviv, creator of the Hamsa Flag Project, reflects on a utopian symbol’s meaning post-Oct. 7

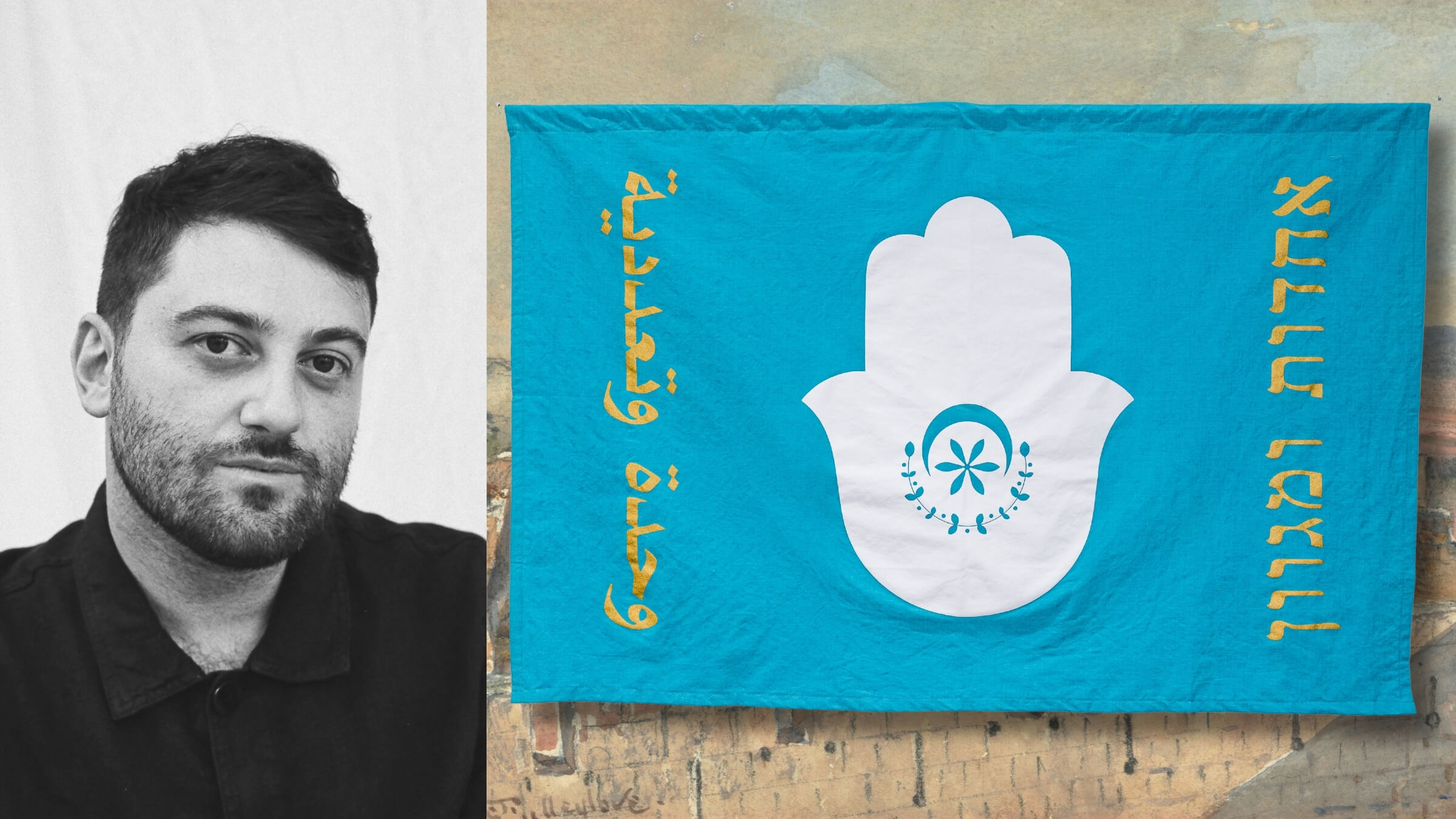

Tom Haviv is the creator of the Hamsa Flag (Instagram:@hamsaflag): a flag for a potential binational Israeli-Palestinian state. Photo-illustration by Ella Pennington / Tom Haviv / Canva / Samuel Eli Shepherd

One flag represents solidarity and strength. Another is code for ethnic exclusion and incitement to violence. Which flag is which? It depends on who you are, and your connection to the conflict on the ground.

A year into the current Israel-Hamas war, symbols representing Israel and Palestine have become more powerful, and also more politically charged. An Israeli or Palestinian flag can inspire deep feelings of both identity and trauma. Israel’s Star of David excludes the land’s non-Jewish inhabitants, whereas few Jewish Israelis identify with the Palestinian flag’s roots in Arab nationalism.

But can a flag exist that encompasses every person in the Levant, regardless of religion, ethnicity or national affiliation?

Artist Tom Haviv wrestled with this question as a college student in 2009. He read an essay about a one-state Israel-Palestine solution in The New York Times that sparked great debate (and not just because it was penned by Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi). Haviv sought to create a flag for a future where Israelis and Palestinians lived together in a single, shared country.

The result was the Hamsa Flag, first introduced in 2015. A white hamsa sits atop a turquoise background. The term “One and Many” runs in Hebrew and Arabic copper text on both sides.

An updated 2019 version of the flag uses the words “Singularity and Multiplicity” instead. Haviv also added a crescent moon and star inside the flag to represent Islam and Judaism, respectively.

Since Oct. 7, more people have been taking an interest in the Hamsa flag by engaging with the project’s official Instagram page, or through purchasing the flag via Haviv’s publishing platform: Ayin Press. In May, Haviv also sold a special version of the flag to raise money for Standing Together: a grassroots organization working towards shared society and equality in Israel-Palestine.

I spoke to Haviv, now 37, on the Hamsa Flag’s rich symbolism and history. We also discussed how the world has been looking at his cloth creation differently since the latest Israel-Hamas war began.

SAMUEL ELI SHEPHERD: You were born in Israel, but you grew up in New York to a blended Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jewish family. How did your Jewish heritages shape your politics as an artist?

TOM HAVIV: My father is Israeli. His family is from Turkey. Originally, my grandparents grew up in Istanbul. My mom is Ashkenazi and from the Bronx. I grew up in New York City in a relatively cultural, secular part of a very Jewish world. I was always wrestling with my relationship to my Sephardic and Israeli identity.

My grandparents were passionate about explaining to me, through stories of their upbringing in Turkey, that there were different paradigms for how Jews existed in the world and how we related to Jewishness.

They made it clear to me that they deeply identified as Middle Eastern people above all, and they were of the Middle East and of the Mediterranean, and they were not separate from it.

In various ways, they shared with me a wider view of history in which Jews had been participants in Muslim worlds, and living within and alongside of Muslim (and many other faith) communities, for at least half a millennium, since the Inquisition. And that they had many experiences of shared society that were not ultimately not mirrored during their lives in Israel.

SHEPHERD Why choose a hamsa as your unifying symbol? Why not, say, an olive tree, or an animal indigenous to the Middle East, like an ibex?

HAVIV: It’s a Jewish symbol and a Muslim symbol. It’s also connected to Christian communities and other faith communities across the Middle East and North Africa and the Balkans. And it’s a symbol that probably predates monotheism.

But it has been integrated deeply into these faiths as a kind of folk amulet and talisman against evil. And it’s ultimately a symbol of protection.

SHEPHERD: Let’s talk about the text on the flag. How did you land on “One and Many” for the first iteration of the flag? And why did that later change to “Unity and Multiplicity?”

HAVIV: I wanted to write something somewhere between a political slogan and a spiritual statement about the possibility of unity among us—a simple statement about shared humanity—while also holding the truth that we are infinitely different.

SHEPHERD: In your view, why do you think creating a new flag is better than reclaiming an old or current one?

HAVIV: The Hamsa Flag project was originally created as an alternative to the Palestinian and Israeli flags, perhaps even to function alongside them—since both fundamentally alienate wide swaths of the necessary publics that would need to sign onto and participate in such a shared society. The goal is to move beyond toxic nationalism of all kinds, especially in Israel-Palestine. This needs to be a flag that represents both Jewish and Palestinian cultures, not to mention the cultures under this flag that are neither Palestinian nor Jewish.

SHEPHERD: Fast forward to 2023 and the current war. Have you noticed a different reception to the Hamsa Flag Project this past year, either through sales patterns or the way people engage with the flag online?

HAVIV: For the six to eight months after Oct. 7, the polarization in America was so extreme and the voices for what some call the “the third way” who were advocating for shared existence in Israel/Palestine were much quieter voices. There is also a lot of pressure in various communities on the left to not work with Israelis or do “joint work” as it is often perceived as normalization.

This past year, it felt harder to bring this project into organizing spaces. I think that hopefully will change in the future. Even our conversation now is kind of an indication that there’s an appetite for that “both/and” kind of story.

SHEPHERD: How do you see your role as part of the mission of moving the conversation – or the political needle – on Israel-Palestine forward?

HAVIV: I think the polarization that we’ve experienced in the Jewish world around what’s happening in Israel and Gaza, it’s made it hard to imagine shared space.

And I think there needs to be a hopeful, and perhaps naive, effort to hold a thread to another depolarized way of moving forward.

The Hamsa Flag Project asks, what ways of synthesis are possible? What phenomena need to occur to create a vision for shared humanity and shared struggle for peace and justice?

Or sometimes I just see myself as someone who’s just trying to steward a simple idea. It’s the idea of a flag of a shared existence between Jews and Palestinians. It’s so simple. It’s not the only offering of its kind, but it’s what I came up with.

That’s what separates it from being a political program. It’s an artwork that is trying to instigate and stimulate imagination. If that ends up being useful and actionable for movement builders or policymakers, great, but these are all things I can’t ultimately control.

SHEPHERD: Speaking of imagination, this has been such a tough year for so many people. We’ve seen a lot of people – both Palestinian and Israeli – losing their imagination, losing their ability to even fathom what you describe as “a third way” forward for this conflict. What helps you keep your imagination from giving into despair?

HAVIV: I think idealism and despair are two sides of the same coin. The flag doesn’t come from an idealistic place, it comes from the despair about an intractable and impossible situation. It arises as a potential healing element. That’s how it arrived in my consciousness.

It’s a dialectic. A dialogue with the loss of hope, the loss of possibility, the loss of shared society, the loss of the Jewish-Muslim shared world, the loss of the idealism of my grandparents who had envisioned an egalitarian, secular state, et cetera.

We’ve all returned to that despair this year. But I do think there is potential in this moment for really recalibrating ourselves to the extent to which we have lost not only so many lives, but so many ideas. And so many kinds of ways of thinking and feeling about the world. I think I said it best in this poem.

I’m hoping that it will bring more people together in relation to despair itself. That it might humble us to the need to collectively dream of other ways of being.