On the road again — except a lot more Jewish than Jack Kerouac, or T.S. Eliot for that matter

Reuven Fenton’s debut novel ‘Goyhood’ interrogates Jewish identity with a jaunty sense of adventure

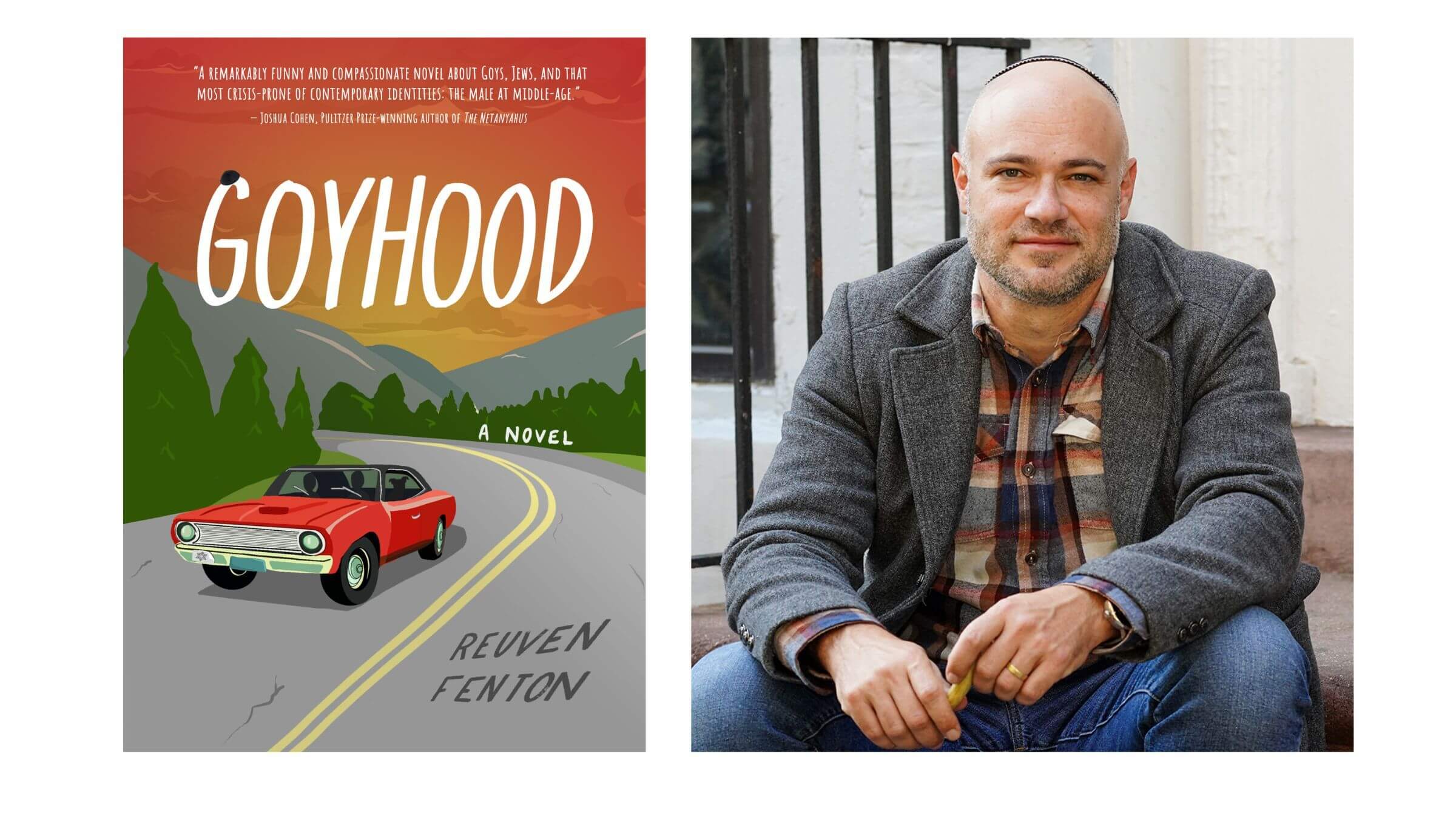

‘Goyhood’ is Reuven Fenton’s debut novel. Courtesy of Central Avenue

Goyhood: A Novel

By Reuven Fenton

Central Avenue, 288 pages, $28

When we meet David and Marty Belkin, as 12-year-old twins in New Moab, Georgia, they’re poised for yet another adolescent adventure. Fast forward to middle age, and the brothers have divergent lives and outlooks. Yet neither has completely transcended those adolescent urges.

That’s the sensibility, and the premise, of Reuven Fenton’s debut novel, Goyhood. A sweet-natured, fast-paced picaresque, the narrative blends the fun of an impromptu, disaster-laced road trip across the American South with a more serious inquiry into American Jewish identity. It’s a breezy read, cleverly plotted and jauntily written, even if a few threads are left dangling.

Fenton, a reporter for the New York Post, seems to have come by his knowledge of Orthodox rituals and belief honestly, perhaps by dint of his studies at Yeshiva University. Sprinkled with Hebrew phrases, and reliant on Orthodox constraints to frame its plot, Goyhood promises the pleasures of recognition for strict believers, and an anthropological primer for the rest of us.

In the prologue, the Belkin boys and their single mother, Ida Mae, receive a visit from the new rabbi in town. To her sons’ shock, Ida Mae declares the family to be Jewish, and the rabbi invites the boys to start preparing for their bar mitzvah.

Their newfound identity sends the twins spiraling in different directions, inevitably imperiling their relationship. As the main action begins, the precocious Marty (now Mayer) is all in on Orthodox Judaism and living in Brooklyn, his life devoted to Torah study. The pursuit is fully funded by his father-in-law, a famous yeshiva dean. Mayer loves his wife, Sarah, who is emotionally closed off, devoid of passion, and nursing a secret or two of her own. That theirs is a problematic match is evident, but the contours of Sarah’s character and motivations are never fully explored or explained.

David, by contrast, has become something of a ne’er-do-well, with pronounced hedonistic tendencies and a penchant for (mostly) bad business decisions. “By his eighteenth birthday,” Fenton writes, “he’d tried twelve illegal drugs, stolen fourteen cars, spent eight months in juvenile detention, hitchhiked through forty-eight states, been in three bar fights, swallowed one live scorpion, smoked fifty-six thousand seven-hundred and forty-four cigarettes, slept with forty-four women and caught two venereal diseases.” The two brothers, once so close, haven’t spoken in eight years.

Then, catastrophe strikes. Ida Mae, a neglectful mother and never the most stable of women, takes her own life, and sends a devastating letter revealing “a deep, dark secret.” The twins discover (modest spoiler alert) that she was lying about their ancestry: Though the twins’ father was indeed Jewish, they lacked the requisite maternal Jewish grandmother. Worse yet, Ida Mae’s own maternal grandfather was an actual Nazi. Suddenly, the religiously observant Mayer, not to mention the devoutly secular David, is a goy.

This is a problem – and one that Mayer, who’s flown South solo for the funeral, tries at first to conceal from his wife (who is now not really his wife). The religious issue can be resolved with a hastily arranged conversion ceremony, easier for Mayer than most because of his knowledge of Judaism. But, at best, that is days away, and there is time to kill. Can Mayer take advantage of this interlude — which another character compares to the Amish Rumspringa — to enjoy the pleasures of the world? And what wisdom might he acquire along the way?

From this zany premise, consequences flow: lessons learned, friendships forged, a fraternal relationship rekindled.

The road trip naturally involves companions: an urn containing Ida Mae’s ashes, a bedraggled, squinty-eyed rescue dog the men name Popeye, and, finally, a female friend and Instagram influencer, Charlayne Valentine, whose goal is to hike the Appalachian Trail. Before they drop her at the southern trailhead, Charlayne (who is Black) has recounted her tragic backstory, inadvertently provoked a white supremacist fireworks vendor, and both charmed and terrified Mayer. The two discover their shared fascination for birds, which prompts David to keep telling them, perhaps presciently, to “get a room.”

But Mayer is, of course, married, pious, loyal, and honest enough to eventually come clean, long-distance, to Sarah. It is always obvious that the road trip will be a means of growth for both David and Mayer. It is less clear whether Charlayne will be Mayer’s spur to restoring and renewing his marriage, which has its comforts as well as its problems — or the key to a new future entirely. That’s one reason we keep reading.

Fenton manages to keep the whole unlikely enterprise aloft with his buoyant prose, humor and eye for sensory detail. The drive through the Blue Ridge, on the way to a surprise sabbath retreat, captures the area’s alpine splendor. “As they advanced,” Fenton writes, “the mountains’ hue tinted sage, then emerald, and finally sun-emblazoned shamrock. Their immensity evoked in Mayer’s imagination beached Leviathans sleeping through the millennia, waiting for a second flood to wash them back to sea.”

Goyhood is, of course, a classic road novel, and goyhood, Mayer decides, is “the state of rebounding from one travesty to the next.” But the progress is as much cyclical as linear. The journey calls to mind T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, with its dictum that “the end of all our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place for the first time.” For Fenton’s dual protagonists, that’s the revelation that seems to hover just beyond the highway’s horizon.