In the dwindling Jewish community of Moldova, one man fights to keep the old traditions alive

For more than two decades, 78-year-old Roman Soibelis has welcomed Jews into his home and their shared history

Roman Sobeilis lives on Salom Aleihem street in the northern city of Beltsy, Moldova. Photo by Stella Mackler

Even if you’ve never met him before, Roman Soibelis will be excited to see you. His eyes bright, his smile, his kippah advertising the coming of the messiah, he’ll welcome you into his home with a greeting that befits the name of his street – Salom Aleihem.

Soibelis lives in the northern city of Beltsy, Moldova, and the door to his home is quite literally always open. A mesh curtain that zips down the middle fills the doorway.

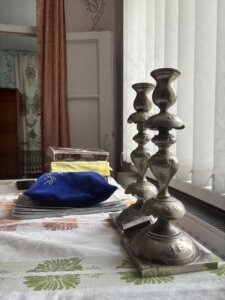

Soibelis, 78, lives alone, in the same house his family moved into in 1956, when he was ten. His house is on a busy corner; there is no obvious driveway. Instead, cars park on an unmarked grassy patch across the street. Blue and green wrought iron gates separate his house from the neighbors. Cracked pavement leads to the entrance to his house. Inside, walls are adorned with faded floral wallpaper and bright-colored rugs. Soibelis keeps his mother’s candlesticks on his kitchen table.

Jewish people across northern Moldova owe their warmth, full stomachs, understanding of Shabbat and a possibly misplaced love for matzah in large part to this man. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Soibelis spent his days trekking to small towns and villages that surround Beltsy in order to provide poor Jewish families with food, water and other aid. He also brought with him a deep knowledge of Jewish tradition. In the newly independent Republic of Moldova, this was a rare thing.

“I started going to synagogue in 1994 when my sister died,” Soibelis said, speaking to me through a Russian translator. “I am still trying to help, provide as much help as I can, or give advice to people who need it.”

A Jewish community always at risk

The story of the Jewish community in Beltsy and surrounding villages is typical of Jewish communities across Moldova. According to Yad Vashem, on the eve of WWII there were somewhere between 15,000-20,000 Jewish people living in Beltsy, and over 200,000 in Moldova as a whole. By the end of the war, practically all of them had been killed.

After a few years, Jews slowly began to make their way back home. Soibelis’ family moved to Beltsy in 1956 from Vertujani, a shtetl near the border with Ukraine. A true Jewish revival, however, was blocked by a severely imposed Soviet atheism. Today, there is a sizable Jewish community in the capital city of Chisinau and small pockets throughout the rest of the country. Their futures, however, are threatened by high levels of out-migration.

For more than 20 years, Soibelis tried to combat that emptiness, volunteering and later working as program coordinator for the Beltsy branch of Hesed on Wheels — Heseds are a network of hyperlocal, nonprofit community welfare centers that opened across the Former Soviet Union (FSU) to serve poor older Jews and children. Heseds were established by and receive funding from the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), one of the largest Jewish humanitarian aid organizations, as part of the JDC’s work to support Jewish communities in poorer and more remote locations.

The Beltsy Hesed opened in 1998 on a side street near the city center. The courtyard is calm and separated from the rest of the world by a tall gate, manned by a quiet security guard. Inside the community center, one of two buildings that houses Hesed, the walls are lined with photographs of community events and volunteer efforts, including Hesed on Wheels. Soibelis’ program supported Jews living in 45 different towns and villages surrounding the city.

“There were villages with just one Jew and anyway we were coming there,” Soibelis said. “We were going there for sure twice per month but sometimes it was needed to go more often.”

The collapse of the Soviet Union plunged an already poor people into even deeper poverty. Hesed on Wheels provided aid that Moldovan Jews could not have afforded on their own.

Sobeilis was one of the people responsible for organizing this service, Roza Lerman, speaking through a Russian translator, told me. Lerman is the director of the Beltsy Hesed’s homecare service. “They were looking for Jews everywhere,” she said. “They were asking people — that was the way Hesed found people. People were not coming but Hesed was looking for them. They were driving around the country looking in all the localities asking if there are Jews in the village.”

According to Lerman, in the early days, villagers greeted Soibelis and Lerman with deep suspicion.

“After the fall of the Soviet Union, they were so in themselves and they were protecting themselves, they didn’t want to speak about their Jewishness,” Lerman said. “They were like, how do you know we are Jews, we are not Jews. Finally [when] they realized this is real help coming and these are real Jews who want to help and support them, they couldn’t be happier. Not only the food, but the possibility to speak and communicate with people of their community.”

The fact that Sobelis spoke Yiddish proved invaluable in his efforts to rebuild a community.

“When we finally started speaking with them in Yiddish about the Jewish tradition and everything, interests, and religion, people started to call to me and ask when are you coming,” Soibelis said. “People were crying and you know these were difficult times when people couldn’t afford buying food and they were saying we do not remember when the last time we ate meat.”

To live, not just survive

In rural Moldovan villages, it was and still is common for every home to grow its own produce. Wild cherry and mulberry trees are abundant. Animals, however, are expensive and require work to feed and house. Winters are freezing. Hesed on Wheels has attempted to ease these burdens. In recent years, the organization has also provided clients with radiators and cell phones programmed with lectures and online events.

“It is only thanks to them that our people started to live, not survive,” Soibelis said.

During the 24 years since Soibelis started working, the number of Jews in Beltsy reached a height of 9,000. Today, there are only about 2,000. The shrinking Jewish population is part of the wider phenomenon of out-migration from Moldova. Since gaining independence in 1991, the country has been wracked by political upheaval, poverty and widespread corruption. If UN Projections hold true, Moldova’s population in 2035 will be somewhere around 2 million people, half of the more than 4 million that lived there in 1989. Young people — young Jews — are leaving.

There is only one synagogue left in Beltsy. The sanctuary is housed in a low, brown building. Soibelis goes as often as his health allows.

“Of course there are Jews, but they are not all interested in religion, not all coming to synagogue,” Soibelis said.

“Maybe even if their parents were religious, they are not,” he continued. “but we are doing our best to not forget that there are Jewish people and Jewish culture.”

Other times he prays at home.

“When people feel bad, they are asking me to say a prayer for them, for their health, for their wellbeing,” Soibelis said. “Each day I am saying prayers for about 15 people. For the work of these people, for their health, and for the health of their relatives.”

Soibelis retired in 2018. In 2014, half of the staff at the Beltsy Hesed was fired as the center was brought under the administration of the Hesed in the capital, Chisinau. Soibelis holds out hope that the community he worked to revive and sustain will long outlive him. But he is uncertain.

“If everything is ok in the world, then I think that our community will also be good,” Soibelis said. “Of course it will be concentrated in the bigger towns and cities mostly, but I know that our community won’t leave. At least I hope for it.”