In Israel, a photographer sees a country whose parts don’t fit perfectly but still form a whole

From the Nova site to the shuk in Jerusalem, seeking the wide view

The site of the Nova Music Festival in the Reim Forest. Photo by Daniel Jackson

Daniel Jackson, an MIT computer scientist and photographer, shot these triptychs during a weeklong mission to Israel this spring. View additional photos from the trip.

When I am photographing a scene, I often want to take in more than my camera allows; to expand the field of view to match more closely what my eyes are seeing. The options to do this are limited. I can take a step back, but then everything in the photo will be smaller and look more distant. Or I can use a shorter lens to widen the image I capture, but that can look unnatural.

Over the last two years, I’ve experimented with a third option: Taking multiple pictures at different angles and placing them side by side. Famous photographers including Richard Avedon, Dawoud Bey and Annie Liebowitz have used this strategy, and some —notably David Hilliard, with whom I’ve studied — deploy it in all their images.

Triptychs (when there are three panels) and diptychs (when there are two) create an effect similar to panoramic images, which were especially popular in the 19th century (and for which special cameras were made). But unlike panoramas, they reveal the seams and mismatches between the individual frames, and sometimes also that the shots were taken at different times.

It is this strategy that I deployed on a weeklong visit to Israel this spring. It seemed apt to the current situation, the divisions in the photographs reflecting the way the country has been fractured by war and politics. The parts are distinct and don’t fit together perfectly, but nevertheless form some kind of whole.

I went to Israel with a group of faculty colleagues. Our goal was to express support to our Israeli counterparts, to strengthen ties among our universities, and to lay the groundwork for new collaborations. I had been to Israel many times before — including a gap year before college — the last time a month before the Hamas terror attack of Oct. 7.

I’ve been making photographs since I was a teenager. My parents let me commandeer a basement room as my darkroom and never complained about bathtubs full of prints being washed. I’ve photographed life around a pond behind a family house for 20 years.

My projects include a series of images of labs commissioned to accompany an exhibit of historic photos by Berenice Abbott; a book of portraits and stories of students, faculty and staff experiencing depression; and porch portraits of neighbors during COVID.

The image at the top of this article is from the site of the Nova festival, Reim Forest, where 364 saplings were planted in January — during Tu’b’shvat, the Jewish holiday for trees —to honor each of the young music lovers massacred there on Oct. 7. The sight of the nascent plants arrayed into the distance brought to mind the war cemeteries of rural France.

Earlier that afternoon, we had met Oz Davidian, an Israeli farmer who rescued more than 100 people from the Nova grounds, ferrying them to safety in his small truck while under fire. As I walked around the open fields, it was hard to imagine the horrors of that day, but the artillery booms overhead were a reminder of the ongoing war a few miles south in Gaza.

Below are four more triptychs.

‘Continuing to learn together’

Universities throughout Israel postponed the start of classes last fall because of the war, worried that clashes between Jewish and Arab students might break out as they had around the last Israel-Gaza flareup in 2021. When we visited Haifa University, we learned that on the first day of classes in December, volunteers had handed out 8,000 bracelets that said “We are continuing to learn together” in Hebrew and Arabic.

Founded in 1972, Haifa is Israel’s most diverse university, with Palestinian citizens of Israel comprising 45% of the student body. At all the campuses we visited, we were moved by the commitment Arab-Israeli faculty showed to a shared society — and saddened to hear that they feel that their loyalty has not been reciprocated.

Israel’s universities have had to manage not only their own challenges, but also the challenges of an unprepared nation. They took a leading role in filling gaps in the government’s immediate response to Oct. 7.

The Technion, for example, hosted hundreds of displaced families, opened daycare and high school facilities, and shipped food, medicine and ceramic vests to soldiers. A group of students at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem created a situation room to manage a nationwide volunteering program.

Ben Gurion University, which is less than 25 miles from Gaza, became a distribution center for the country’s south, and engaged 500 medical students to treat people wounded on Oct. 7 and afterward. The first group that they attended to were Bedouin who suffered burns when rockets from Gaza hit their neighborhoods.

Modern problems, ancient texts

Our trip was during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, and one night we attended a break-fast with Mansour Abbas, one of the 10 Arab members serving in Israel’s 120-seat Parliament. Under his leadership and the prime ministership of Naftali Bennett, Abbas’s party, Ra’am, in 2021 became the first Arab party to join a governing coalition. Now, he is back in the opposition and though he condemned the Oct. 7 attack, Israel’s right-wing national security minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir, nonetheless denounced him as a “terror supporter.”

Abbas serves as imam of a mosque near his home in the Galilee. His conservative views have drawn criticism, but he has been widely praised for his bridge building efforts. During the Arab-Jewish riots in Lod in May 2021, he visited burned synagogues and vowed to help rebuild them. He has also condemned the Oct. 7 attacks more forcefully than any other Muslim politician.

In his meeting with us, Abbas quoted from both the Koran and the Torah. He argued that human values of loving the other must take precedence over nationalist goals, and that only a repudiation of radicalism on both sides could bring about a peaceful future. And he said that a Palestinian state would not be a reward for terrorism but a terufah, a healing.

Our meal was held in a restaurant in Daliyat Al-Karmel, a Druze town about 10 miles from Haifa. The owner, Nura, made a traditional Druze spread; dessert was qatayef– deep-fried pastries in the shape of the crescent moon, a Ramadan specialty. She told us that Druze have always been happy to live among Jews because we also “choose life.”

The market goes on

Mahane Yehuda market is a favorite for locals and visitors alike. For me, there’s no better lunch than a meandering walk around “the shuk” buying an array of pastries, olives, cheeses and fruit.

The market was a ghost town for weeks after Oct. 7, but has been back up and running for months, albeit more subdued than before. Even though I only had one day in Jerusalem on this visit, I spent several hours there, photographing the young people offering halvah tastings, the older storekeepers, and groups of soldiers on break.

Fitting the parts together

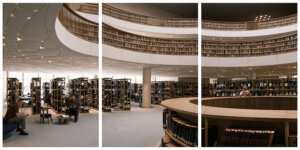

The new National Library, designed by the Swiss firm Herzog and de Meuron, opened its doors just weeks after Oct. 7. The opening was seen as a totem of Israeli resilience, and the soaring reading rooms have provided respite for thousands during these tumultuous months.

Sitting in the left of my photo is Daniel Taub — an old friend, former Israeli ambassador to the U.K., and director of strategy and planning at Yad Hanadiv, the foundation that funded the library’s $220 million construction.

The library embodies past and future; rare Hebrew manuscripts that are too fragile to be displayed continuously can be viewed with a robot that lets you make a selection and then brings the item up to an illuminated glass panel. The collection includes more than 2 million photos, including one of the shuk in 1948, looking very different from today’s.

Israel’s distinct parts present challenges but are also the source of its strength. The future will surely belong to those who are committed to preserving these many parts but also working to ensure that they fit together a little more smoothly.