Are Jewish horns having a comeback? The history behind the antisemitic stereotype

Recent depictions of pro-Israel politicians and university presidents are on the horns of a new dilemma

Protesters carry a puppet of a horned Benjamin Netanyahu dripping blood from his mouth. Courtesy of Getty Images

When Benjamin Netanyahu spoke to Congress this past July, protesters marched through the streets carrying a giant effigy of the Israeli prime minister, horns arcing from his forehead.

When other pro-Palestinian activists sprayed red paint on Cas Holloway’s apartment door, they dropped flyers depicting the Columbia University executive behind bars with small red horns protruding from his scalp. Holloway isn’t the only university official who has been given horns by pro-Palestinian groups on posters and in graffiti.

Horns, at least in the West, generally invoke devils, demons, imps or other various beasts of hell. They also have another referent: Jews.

For centuries, Jews have been depicted as horned in art and illustrated manuscripts; Nazis used the same imagery in antisemitic propaganda. The stereotype was so pervasive that even today, Jews have anecdotes of being asked to remove their hats or kippot so that people could check for their horns, or questioned about their tails and hooves.

It is hard to say whether those fashioning horned images for protests today are aware of their antisemitic history; it’s possible, and even likely, that they simply intended to critique both leaders by implying that they are evil, like the devil.

But those comparisons were core to the historical antisemitic propaganda as well. And particularly given the anti-Zionist thrust of the criticism, the resonances with antisemitic propaganda are hard to ignore.

A history of horns

The association of horns with Jews began with a mistranslation of a passage about Moses descending from Mt. Sinai with the Ten Commandments. The Hebrew text describes something surrounding Moses’ face as he entered the Israelite camp; Saint Jerome, an early Christian priest who translated the Hebrew Bible directly into Latin, took a word that could mean “rays of light” or “glory” and translated it as horns. While others may have made similar mistranslations, Jerome’s version of the bible, known as the Vulgate, became the accepted translation in the Catholic Church.

Whether or not Jerome portrayed Moses as horned out of malice is unclear — horns were often a positive symbol in the ancient Middle East that indicated power and divinity; Egyptian gods, for example, were often depicted with horns. But the priest had no fondness for Judaism; while he studied with Jews in Jerusalem to improve his Hebrew, he also cursed Jews in his writings for not accepting Christianity. And within Christian tradition, thanks to depictions of a horned antichrist in the Book of Revelation, horns were not seen so positively.

Either way, the depiction of a horned Moses stuck. In a symbolic map, the Hereford Mappa Mundi, a horned Moses stands near the dragons guarding the gates of hell while other Jews worship a demon and the Golden Calf.

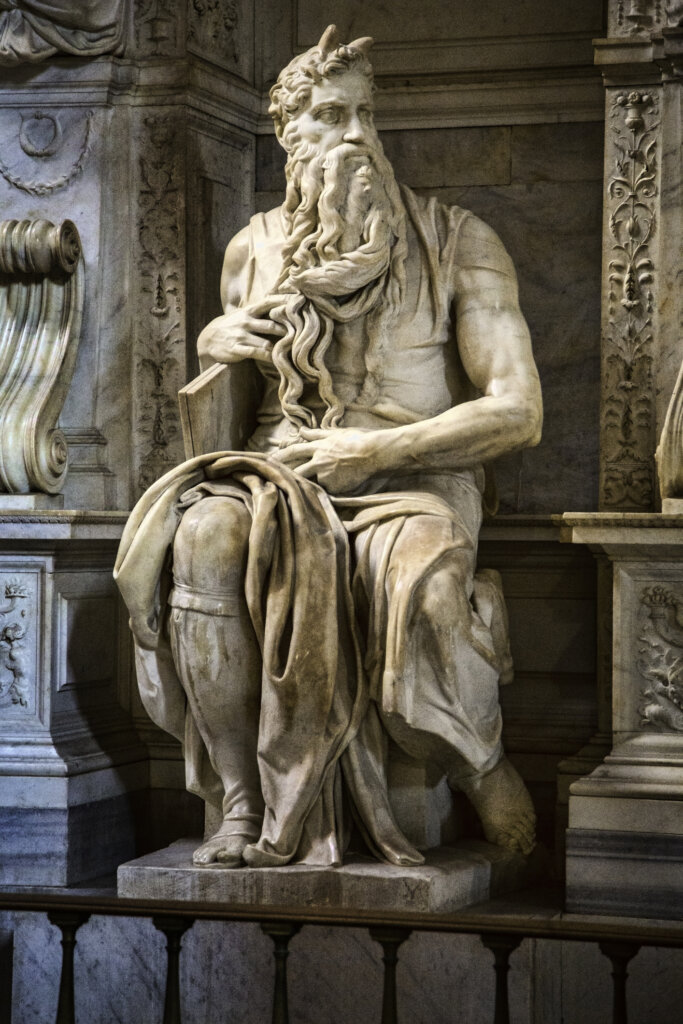

And perhaps most famously, Michelangelo depicted a horned Moses in a marble statue commissioned by the Vatican, though that image is generally seen as a positive portrayal.

How Jews grew horns

Horned Moses imagery became less common in art around the 16th century, when it became generally known that the translation was inaccurate. But by this point, the association of horns with Jewry had been established.

As imagery of horns continued to develop, they became increasingly associated with devils and, generally, evil. Portrayals of Satan frequently depicted him with horns or tusks, and often the hindquarters of a goat, likely drawing from pagan and Greek iconography that Christianity sought to discredit.

Judaism, too, was considered a bygone, false religion worthy of derision, so the association of horns with Jews was simply logical, especially given the history of depicting a horned Moses. It became so common to depict Jews as horned that even everyday folk art, outside the church, used horns to signify Jews along with other negative Jewish physical stereotypes such as a large hooked nose.

Eventually, the Jewish horns and the demonic horns became one and the same; antisemitic conspiracies circulated alleging that Jews were demons. People alleged that Jews could shapeshift at will, and could be identified by the traits they shared with Satan: cunning and trickery.

Horns as a symbol for Jews

Jews eventually were required to wear a symbol of their horns, either a hat or a badge. Yellow badges worn by Jews were sometimes circular or in the shape of the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments, but sometimes also in the shape of horns. And though pointed hats were once commonplace and worn voluntarily, they later became required as a symbol of Jewishness; in Latin, the hats were referred to as the “horned skullcap.”

The hats, like the literal horns they may have represented, acquired antisemitic connotations in art. Jewish biblical heroes — including, ironically, Moses – were sometimes depicted without hats, to show their goodness, while non-Jewish but evil figures, such as the Pharaoh’s magicians in the story of Exodus, would wear the pointed hats to indicate they were on the wrong side of the story.

When Jews were expelled from villages during the plague, the pointed hat took on a connotation of criminality and, eventually, an association with sorcery. (Fewer Jews were struck with the plague, which led many at the time to blame Jewish magic for its spread.)

A conspiracy of demons

Not all of the criticism of Netanyahu at the protest outside of Congress relied on horns, of course; there were even several other effigies of him — one dressed him in a prison jumpsuit, and another in a normal suit.

But the horned puppet, which also featured blood trailing from the papier mache prime minister’s mouth, was the largest and most visible, requiring several people to hold aloft. And for many, it felt like a return of several antisemitic canards: not only the horns, but also blood libel.

And, though Cass Holloway is not Jewish, invoking the same devil horns to criticize him for his stance on Israel, evokes the same antisemitic histories.

There is, unsurprisingly, a long history of comparing political adversaries with demons. The is a well-known symbol of evil, meaning even the most passive audience will understand the message. Plus, implying that the power of God is on your own side is a powerful message, and lends a supernatural, spiritual weight to the charges against any opponent.

But generally, depicting any group as devilish has had ties to deeper conspiracy theories — not just a critique of actions or stances, but an implication that they have been corrupted by something deeper and more supernatural than politics. Demons are a fallback that allow criticism of a person or institution not just on merits, but because of something mysterious and dangerous.

The devil was a part of anti-indigenous rhetoric in early American colonies and for centuries was frequently portrayed as Black, as part of efforts to imply the fundamental evil of slaves; both were ways to encourage racism against minority groups.

In the past few years, commentators positing that demonic influence is behind the fights for reproductive and LGBTQ rights have grown. And then there are conspiracy groups like QAnon pushing allegations that demons are running the “deep state,” giving them control over the government, academia and the media.

And if that sounds a lot like another antisemitic conspiracy theory, well, it’s no surprise.