Is every war movie about Israel and Gaza now?

People are finding parallels to the war in, well, everything

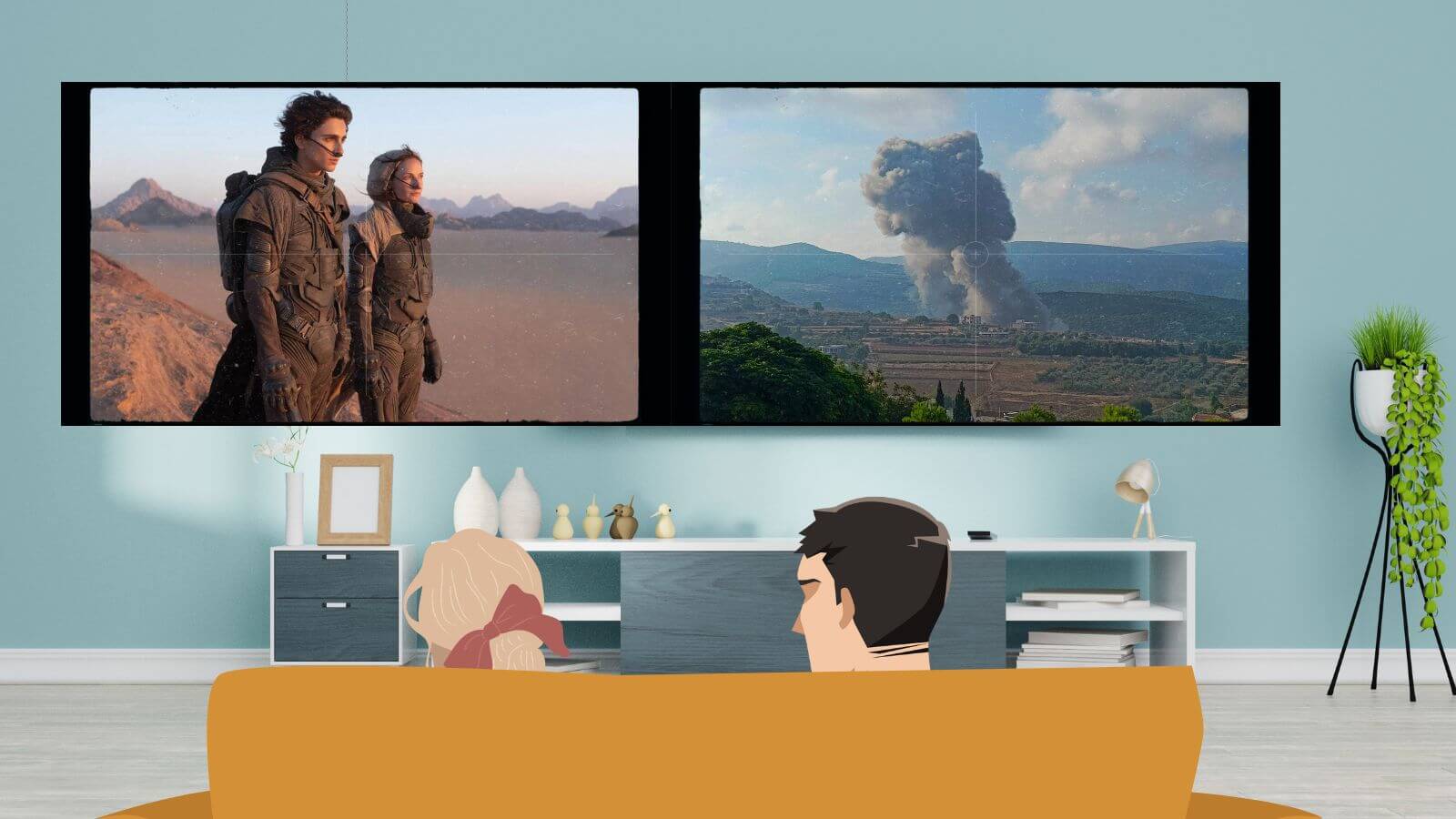

Is it a war movie or is it the real war? Courtesy of iStock/Canva/Mira Fox

When the second installment in the blockbuster Dune franchise came out this year, it was hard not to see it as a not-very-subtle metaphor for the Israel-Hamas war. It felt strange to watch scenes of guerilla warriors in headscarves and veiled women fleeing through the desert in IMAX when I saw the same images on the news.

But lately, people have been finding those same parallels in, well, every movie or TV series or story about war or conflict.

Of course, sometimes that’s because they’re meant to. The themes of the new season of The Last of Us, a hit zombie TV series based on a video game, were inspired by game creator Neil Druckmann’s experience growing up in an Israeli settlement, both in its broad themes of violence and revenge, and in its details, such as a rebel group that operates via secret bridges, reminiscent of Hamas’ tunnels.

And Dune’s author Frank L. Herbert drew on American imperialism and oil ventures in the Middle East, along with the stories of Lawrence of Arabia. Sure, it wasn’t meant to be a parable about Israeli occupation, but its visual references to keffiyeh-clad Arab fighters were intentional.

Other times, the interpretations have clearly come out of the context viewers have been living through. Civil War, Alex Garland’s film about, well, civil war, follows photojournalists as they drive through a war-torn U.S. The message, at least on the surface, is about the dangers of political polarization. But the film focuses on the stories of the painfully neutral journalists, who remain on the sidelines even in the thick of a conflict that clearly impacts them. Commentators have tied the film to the debate over the role of journalists in covering the Israel-Hamas war.

But the Israel comparisons aren’t limited to media released since the war began. Game of Thrones, The Hunger Games, Star Wars, Apocalypse Now and even The Godfather — someone out there has argued that they are metaphors for Gaza.

In Game of Thrones, the beautiful Daenerys, a heroine for most of the series, slaughters thousands of civilians with her dragons, a fact that some now compare to Israel’s actions in Gaza. Panem, the bloodthirsty Capitol in The Hunger Games that subjugates the outlying Districts, is a metaphor for Israel’s occupation. Hamas is compared to The Godfather’s Don Barzini because both negotiated in bad faith for an end to the war — or something. I didn’t quite follow that one.

Of course, the beauty of the best art and media is its ability to be interpreted and reinterpreted. That’s what gives Shakespeare and even the bible staying power. And the Israel-Hamas war is dominating the world right now, so it makes sense that people are seeing it in basically every piece of art and media they consume, consciously or subconsciously close-reading for parallels they can apply to their worldview.

It’s not that these films don’t have insight to offer about the Israel-Hamas war, or the conflict more broadly; they do. But part of the trend is boiling every movie about war into a clearcut moral parable: Israel as the hero or Israel as the villain. And that means refusing to really engage with the art.

People love to assign characters in Dune to sides of the war. But this obfuscates the other, more nuanced, commentary the movie has to offer. The messianic hero of the series is an outsider to the desert land, part of an occupying force; if you keep to the Israel-Gaza metaphor, it would imply Palestinians can only be saved by an Israeli, a conclusion that most activists would take issue with. But in fact, the hero of the movie isn’t all that heroic, in the end. The occupiers and the occupied are all pawns in a larger game. There’s more to the story than good vs. evil.

Civil War’s depiction of the futility of journalism, its inability to truly impact world events, doesn’t just critique journalistic neutrality, but poses greater questions of how we consume media today — whether what we read and watch actually changes how anyone thinks or acts, questions as relevant to the upcoming U.S. election as they are to the war.

And The Hunger Games offers good insight into propaganda and strategies to manipulate the public, which could be applied to the war, sure, but also life in a capitalistic society more generally; we’re willing to look past all kinds of abuses — football players’ head injuries, child labor in the factories that manufacture our TVs — if it leads to our own pleasure, just as the series’ wealthiest residents delight in watching children kill each other in creative ways.

We live in an era in which people seem to want their media to be didactic. White Lotus and Succession, shows that skewer the wealthy, were both criticized on social media for having sympathetic characters. Allowing the rich to occasionally be relatable supposedly weakened their class commentaries — even though the reality is that few people, no matter how morally corrupt, are completely inhuman. (Meanwhile, Barbie’s exhaustingly literal speech about feminism received glowing accolades.)

So it’s unsurprising that people are looking for reductive morals about the Israel-Hamas war, and missing — or rejecting — the complexities that every good story can inject into a black-and-white narrative. It’s uncomfortable to grapple with the ways your worldview and choices might be fraught; it’s much easier to be told exactly what to think.

But good stories aren’t polemical; they challenge our thinking instead of reifying it. It’s not that Dune or Game of Thrones or The Hunger Games can’t help people think about Israel and Gaza — it’s just that they can do so much more than that. Searching for simplistic moral frameworks reduces art to a predictable, hollow message: my side good, your side bad. And isn’t that boring?