Why are Jews calling anyone who disagrees with them a kapo?

The term is one of the harshest insults between Jews, yet somehow it has become just another political epithet

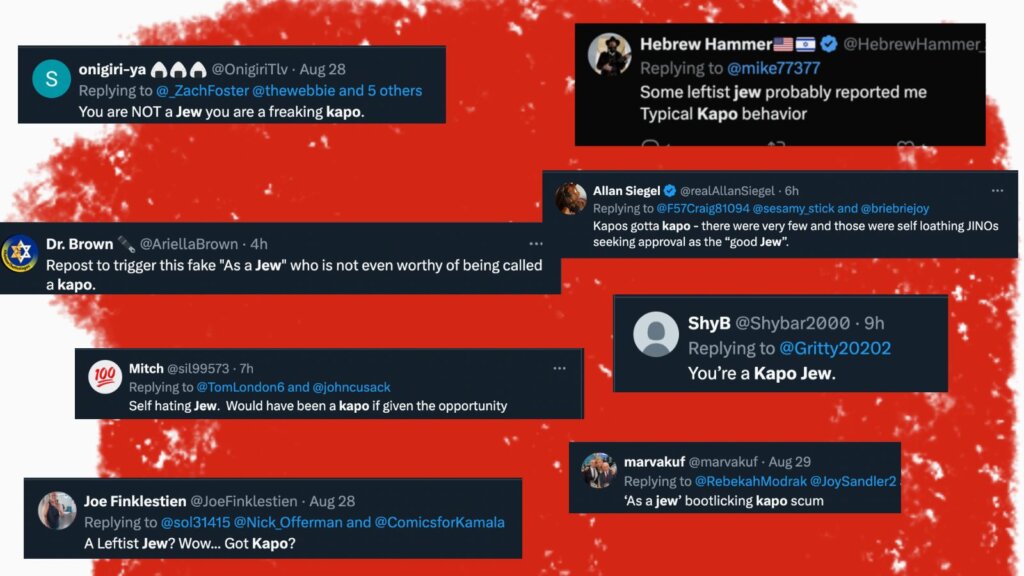

Intra-Jewish insults are becoming common political epithets. Image by Mira Fox

Every journalist gets a smattering of unhinged hate mail from angry readers. But if you’re a Jewish journalist, I bet some of those emails have accused you of being a kapo; it’s happened to me, and it’s happened to my colleagues. And it’s not limited to journalists; the slur has been increasingly slung around as an insult online.

The term kapo originally referred to Jewish inmates at Nazi concentration camps who were assigned to assist the Nazis in overseeing the other inmates. They took roll calls, helped to prevent escapes, ensured that work in the camps ran efficiently and sometimes informed on their fellow prisoners; in return, they usually received slightly better treatment or perks such as more food or cleaner quarters.

Kapos are also commonly considered traitors to the Jewish people. Hundreds of kapos were lynched by their fellow prisoners upon the liberation of the camps, and more prosecuted after the war by tribunals in Israel and abroad. It is one of the harshest insults a Jew can use against another Jew, an accusation of betrayal of self and people.

I try to delete threats and name-calling from my inbox for my own sanity — though I’ll write back if you have a real comment or critique — but a brief search for the term “kapo” in my email brought up plenty of fodder.

I was called a kapo for covering positive memes erupting about Kamala Harris — or “Amalek Harris,” as the sender called her. There’s also a slew of emails addressed to the entire Forward staff that call us all kapos and “ghetto Jews”; the articles they complain about include both news pieces on Gaza and movie reviews.

Whatever the exact thrust of the insult, it’s increasing in frequency. But why has kapo become the go-to slur among Jews?

The tortured history of kapos

It’s no accident that kapos and Judenrat, the Jewish councils that oversaw the ghettos and helped round up people to be deported, were hated; that was the point. The idea of using fellow prisoners as guards and functionaries came straight from the mind of Heinrich Himmler, the architect of the Holocaust.

The creation of kapos and the Judenrat were both a cost-saving measure — if prisoners policed themselves, fewer SS soldiers were needed to oversee the camps — and a tactic to create internal division and unrest that would weaken the Jewish community.

“A kapo gets special privileges. The minute we are not satisfied with him he stops being a kapo and goes back to sleeping with others,” Himmler told a gathering of German generals. “He knows only too well that they will kill him on the first night.”

Immediately after the Holocaust, some kapos and Judenrat members were killed by partisan groups and community members. In displaced persons camps, “honor trials” were held to determine who had survived by betraying their fellow Jews. The new state of Israel passed a law against not only war crimes, but “crimes against Jewish people,” holding a series of so-called kapo trials from 1950 until 1972.

“There were nine million Jews in Europe, six million of them were killed, yet there were pretty few instances of collaboration and treason,” said John M. Efron, professor of Jewish history at the University of California, Berkeley who has written a book on German Jewry in the post-Holocaust period. “I think those that did take place stand out all the more starkly as aberrant.”

But over time, and as scholarship about the Holocaust grew, the understanding of kapos shifted. Historians such as Yehuda Bauer questioned the idea that Jews were led “like sheep to the slaughter” and expanded the idea of resistance beyond armed rebellion; others such as Primo Levi wrote about the “choiceless choices” the Holocaust foisted upon Jews, including kapos.

“I think this kind of scholarship was instrumental in helping understanding, and with understanding comes a sense of compassion.” said Efron. “There is, I think, kind of a difference between being a real traitor and someone who assisted the Nazis — someone who’s like the head of a ghetto, head of a Judenrat, and it’s either you give us 6,000 children tomorrow morning or we’ll put a bullet in your head.”

Eventually Israel wound down the kapo trials; fewer and fewer were found guilty, and previously imposed jail sentences were commuted. But the term remained in use.

Kapos become political

Even as the real kapos were largely forgiven, or at least left unpunished, the term remained a symbol of the worst kind of betrayal. Today, it’s used freely as a slur between Jews, divorced from its literal meaning to be a symbolic accusation of traitorousness. And that treason is often political.

“For a while it was reserved for outliers like anti-Israel activists. But recently I’ve seen it used for every Jew who doesn’t support Trump,” said Howard Lovy, a writer currently working on a book about fighting antisemitism; he says he has been called a kapo numerous times. “It’s rooted in political nastiness. I think it has less to do with my position as a Jew and more my position politically on the spectrum in the United States.”

The idea that opposing or criticizing Israel is a betrayal of one’s fellow Jews is not a new one. The two biggest events for world Jewry in the 20th century were the Holocaust and the creation of the state of Israel, and it makes a certain kind of sense to borrow vocabulary from one to apply to the other.

But the word’s valences have grown to include a broader spectrum of stances. And the insult always seems to run in the same political direction: from the right, against the left.

Efron, the Berkeley professor, said kapo may have become common for political disagreements among Jews because of something relatively simple: It is a secular insult. And politics, whether around Israel or around the presidential election, is a secular topic.

“Jews have not been shy in attacking each other since the year zero, right? And up until relatively recently, up until the middle of the 20th century, it’s always been about the way that one practiced Judaism,” he said.

But “kapo” comes out of a part of Jewish history during which Jews were persecuted because of their ethnic identity, and it implies a betrayal not of religious tenets, but of communal mores. It relies on a more modern definition of Jews as a secular identity group, not a religious affiliation.

“We live in a secular world so they reach for a secular term of opprobrium,” Efron said.

Yet Jews on both sides of the political spectrum see the other party as betraying their fellow Jews. Trump moved the embassy to Jerusalem, his supporters often point out, so opposing him is synonymous with opposing Israel. Yet his detractors might reference his friendliness with antisemites and white nationalists, arguing that supporting Trump is akin to supporting Nick Fuentes or the Charlottesville neo-Nazis. Each side of any Jewish divide denounces the other as bad Jews. But for the most part, it seems like only one side calls their enemies kapos.

So why does the insult only travel in one direction? The reasons may be a complicated mess of political strategies, communal norms and feelings toward Israel. But it also may be something more simple: Trump’s habit of making up insulting monikers for his political adversaries has made name-calling a fundamental part of modern day Republican politics. (“Tampon Tim” and the rather confusing “Kamabla” are his most recent coinages; there’s a running list on Wikipedia.)

“We live in a political climate that’s totally intemperate,” Efron said. “You can just say anything with impunity, especially if you’re some sort of keyboard warrior.”

I can’t wait to read my email after I publish this article.