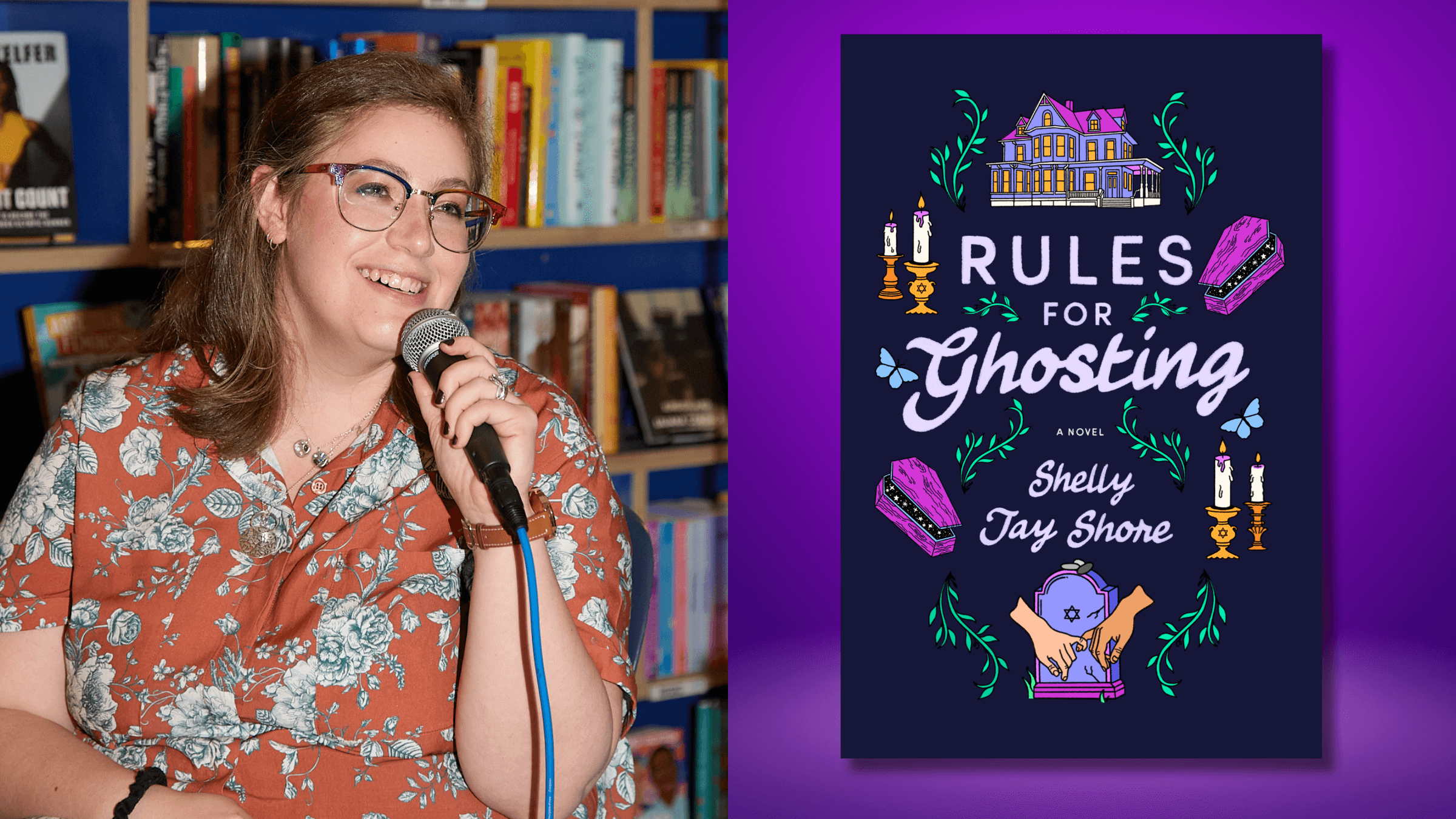

A Jewish, queer ghost story where the greatest fright is family expectations

A conversation with Shelly Jay Shore on their debut novel, ‘Rules For Ghosting.’

Author Shelly Jay Shore says their novel is more about “Eldest Daughter Syndrome” than ghosts. Graphic by Pierce Bartman (photo), Elena Giavaldi and Amy Perez (book cover), Samuel Eli Shepherd (graphic)

Shelly Jay Shore initially wanted to write a romantic comedy set in a funeral home. The Jewishness — and the ghosts — came later.

Shore, who uses both she/her and they/them pronouns, said the inspiration for the novel came from attending a friend’s funeral in 2019. The eulogy discussed Jewish end-of-life rituals, which Shore knew little about at the time.

“I wanted to have that represented on the page, because that wasn’t something I had ever seen in fiction,” Shore said.

Two years later, Shore found themselves stuck at home during the pandemic. It was an intense time. Shore had just been laid off from their job, they were mourning their recently deceased grandmother and they were looking after their newborn baby.

Searching for a creative outlet, Shore returned to an incomplete draft of an abandoned romance novel buried deep in their Google Drive. She finished the draft in early 2021. By November, they sent a version out to publishers.

“This was a pandemic baby,” Shore said. It was also, as she put it, a “grief project.”

Despite the title, Rules For Ghosting, Shore’s fiction debut, is light on horror and heavy on humor, heart and family meshugas.

The story follows Ezra Friedman, a twenty-something nonprofit worker and yoga teacher living in Providence, Rhode Island. When the Friedman funeral home gets into financial trouble, Ezra returns home to help out his family’s business. A romance blossoms between Ezra and a funeral home volunteer named Jonathan, while Ezra’s family life implodes.

Ezra is a queer, transgender man. That detail is far less noteworthy than the fact that Ezra can also see ghosts, including the clients in his family’s funeral home and his crush’s dead husband.

It’s a Casey McQuiston romance meets a Neil Gaiman fantasy, all sprinkled with the dysfunctional Jewish family chaos of an early Philip Roth novel (minus the misogyny). I spoke to Shore about Jewish death rituals, kosher marshmallows and the joy of creating a story where a character’s queerness and Jewish identity can comfortably coexist.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

SAMUEL ELI SHEPHERD: Rules For Ghosting goes into depth about various Jewish death rituals like taharah, the ritual of preparing the body for burial. These are a lot more specific than just sitting shiva or reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish. How familiar were you with Jewish end of life rituals before writing this book?

SHELLY JAY SHORE: Not very. I grew up very Reform, and I married into a more observant family, but not a family that was deeply ingrained in community death rituals.

I knew the whole thing with shoveling dirt with the back of the shovel, and I was familiar with the idea of Shemira, which is the practice of not leaving someone unattended after they’ve passed away. But everything else was fairly new to me.

SHEPHERD: So who did you consult to make sure you got the details right?

SHORE: One of the first things I did was reach out to a good friend of mine who is a member of the Chevra Kaddisha of Greater Boston, and we had a really great conversation about the ways these rituals have evolved to meet modern community needs.

We spent a lot of time talking about trans-inclusive rituals and about gender-inclusive rituals, which was also really important to me in the book, as it comes up several times.

I also spoke to someone from Plaza Community Chapel in New York. That was a really good conversation about the sort of logistics of funeral home work: what happens when the call comes in, what kinds of things are done on site, what kinds of things are not done on site, how funerals are organized, that kind of thing.

In general, the conversations were much more enlightening than the reading list, which was not as meaningful as speaking to someone who’s actually doing the work.

SHEPHERD: The Friedmans are a religiously observant family, and this book is hyper-specific about Jewish traditions. (This is the first time I’ve seen kosher marshmallows represented in a novel.) Why was it important to you to write a book that emphasized the ritualistic aspect of Judaism, rather than necessarily Jewish religious belief or even culture?

SHORE: There’s a really rich tapestry of Jewish life, and I wanted to show one of the threads of the tapestry that I think is not super common in fiction.

I think that something we don’t see a lot of are ritually and liturgically fluent Jews who are not necessarily deeply observant. Ezra is culturally Jewish and not super observant, but he actually knows quite a lot.

I wanted to make it really clear that you can be connected to ritual and connected to tradition without necessarily being observant in your daily life.

SHEPHERD: Rules For Ghosting addresses topics like anxiety, family trauma and death head-on. Yet the story is still ultimately a cozy and sweet romantic comedy. How did you manage to find the right tone for your novel such that it balanced all these tough emotions but never ventured into too dark a place?

I think that the core of it is that this family really loves each other. The friends that Ezra makes really love each other. And I think that’s what keeps it from feeling hopeless.

SHEPHERD: Right, and a large part of that is because Ezra has such a strong support system. In your book, Ezra has a close relationship with both his family and his close circle of mostly queer friends. Why was it important to emphasize both Ezra’s family of origin and his “chosen family”?

SHORE: I think in a lot of queer fiction especially, there’s this idea that you have to choose between your family of origin and your family of choice, and I think in reality, for many people, that’s not actually the case. I think that many people have a very robust chosen community without giving up the connections that they have to their families of origin.

Of course, stories where families are not affirming need to be told, but I also wanted to show that sometimes these things can coexist really beautifully.

SHEPHERD: Similarly, this is not a “coming out” story. Ezra has a strong sense of his trans identity from the story’s onset. Why was it important to you to write a story about an observant Jewish family where the protagonist’s queer identity was not the primary concern?

SHORE: I wanted to write a queer Jewish story in which queerness and Jewishness were not in conflict. And at no point in the book really are those two things in conflict for the main characters.

Ezra’s story is informed by him being queer and Jewish, but this book is not about him being queer and Jewish, right? None of the problems that he’s dealing with are because his family is Jewish, or because he’s queer, or because he’s trans.

The most prominent problems that he’s dealing with are capitalism, anxiety, and family drama. The aspects of the characters’ identities still inform their decisions and their lives, but the actual conflict and the actual story is about broader themes.

And that’s where we want to go, I think, in fiction. Like any marginalized community, these are important pieces of the character, but it doesn’t have to be about your marginalization for it to be your story.

SHEPHERD: What’s next for you after this book?

SHORE: My second book is about a golem and a musician that go on a cross-country road trip. It’s about humanity and perfectionism and about figuring out who you are when you’re on your own, and whether or not it’s okay to say no to people when you’re used to only saying yes.

SHEPHERD: So basically, another queer Jewish fantasy about anxiety. Keeping it consistent.

SHORE: Exactly.