A Golem grows in Brooklyn — but do Jews need it?

Adam Mansbach’s ‘The Golem of Brooklyn’ updates a Jewish legend for the antisemitism of today

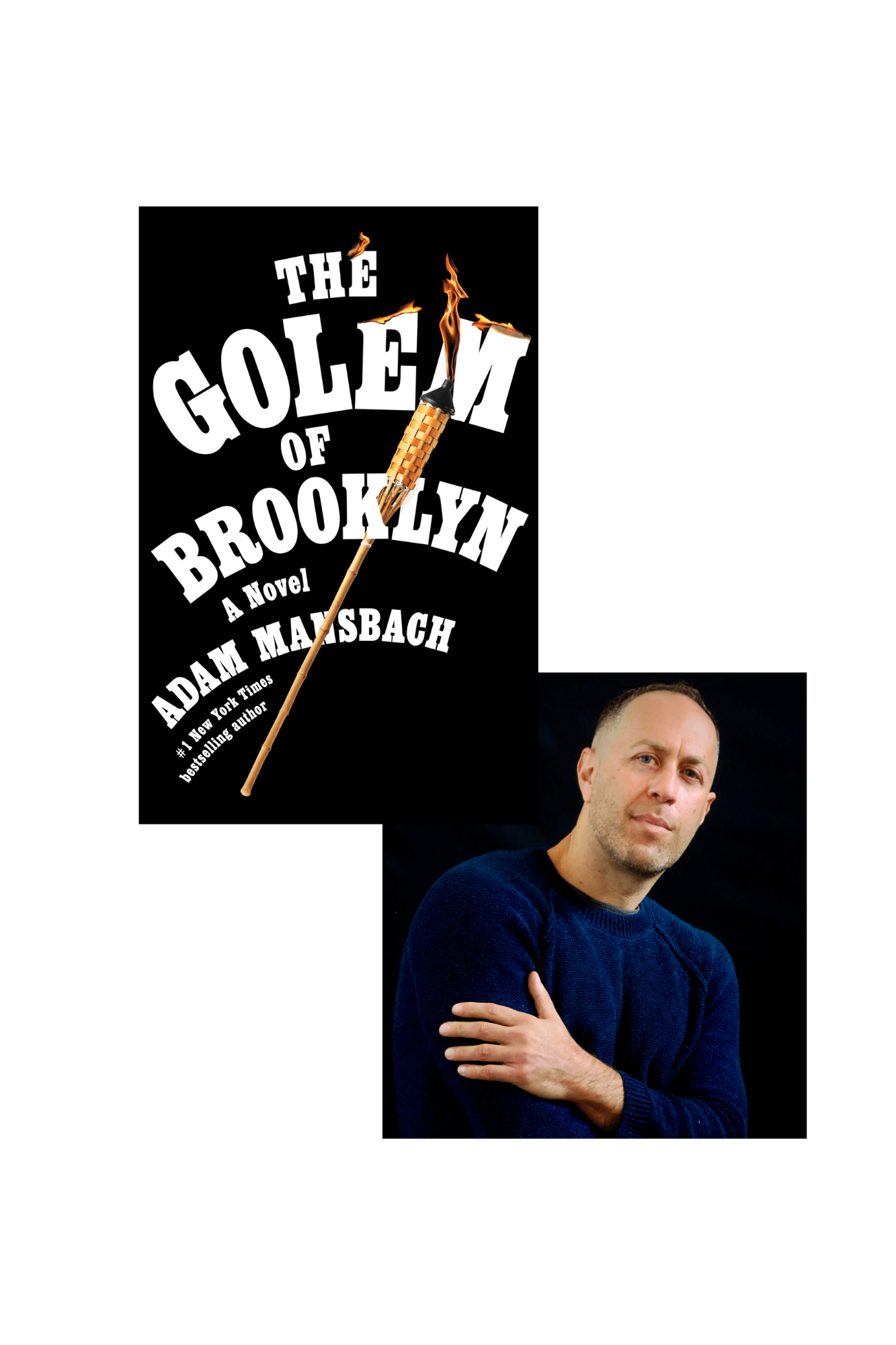

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The Golem of Brooklyn

By Adam Mansbach

One World, 272 pages, $18

No creature from Jewish folklore has made as sizable a literary dent as the Golem. There’s a reason we keep bringing him back.

Talmudic literature refers to Adam as a “golem” before he was vivified by God’s breath. Later, as clay-hewn avenger, the Golem figured in legendary escapades of medieval rabbinic sages hoping to safeguard their people.

This not-quite-alive being, made to defend Jews from pogrom and expulsion, may have inspired Mary Shelley’s tale of a reanimated corpse in an age of industrial anxiety. (The legend made its mark on Weimar film in the period before the Third Reich.) In 2000, the Golem offered a poetic escape from 1930s Europe for a protagonist in Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer-winning novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay. More recently, the Golem’s origins served as a fable of immigration in Helene Wecker’s The Golem and the Jinni and its 2022 sequel.

Now comes a new entry in the canon, Adam Mansbach’s The Golem of Brooklyn, a novel that offers a ready-made metaphor for its shoddy construction and its own, infelicitous question: Do we really need a golem right now? Mansbach, a writer best known for Go The F– to Sleep and the author of a few previous novels, is more uncertain than his predecessors.

In Mansbach’s imagining, “The Golem” takes the definite article — he’s the only one. Like the matter he’s made from, The Golem can never be destroyed, merely reconstituted in a time of peril. He is the same hunk of clay from Moses to the Maharal of Prague, remade with the same consciousness by prophets and holy men and, in this squishy satire, Len Bronstein, a culturally Jewish art teacher who “was not so much in need of a golem as he was in possession of a large quantity of clay” plundered from his classroom studio.

If Len was a sculptor, but then again, no. He only makes The Golem because he’s high and bored, etching on the creature’s animating letters with a wooden chopstick between ears that resemble “clumps of sun-bleached dog shit that someone had decided to glue on a human head.” The Golem wastes no time springing to life and doing some light property damage while speaking in the third-person like the Hulk — only in Yiddish.

Len recruits Miri, a fresh-off-the-derech lesbian, to translate. But by the time Len and Miri arrive to chat, The Golem has learned English from Curb Your Enthusiasm, and somehow from it, picked up his new favorite word, “dickhead.” From these early chapters, brimming with belated observations about Brooklyn gentrification and hipsters, this unlikely trio hits the road to find The Golem’s purpose in the era of the alt-right.

Well, not exactly yet. First we have to hear Len’s friend and dealer Waleed’s pitch for a movie about the Harvard researcher who masturbated an adolescent dolphin. That’s after we hear the spiel about Len’s speculative fiction novel about a scientific couple who are able to timestamp epigenetic trauma.

It seems like Mansbach is using the book as a clearing house for ideas he wasn’t able to realize — his own “large quantity of clay.” It’s a reflex that is at its strangest when observing Miri’s roots in the Brooklyn Sassov community.

It’s important to note that this Sassov dynasty bears little resemblance to the real-life Sassov dynasty, which has no major presence in Brooklyn. Rather, this group of Hasidim is an immensely influential enclave that has outgrown its living situation in the city and is seeking, through political bribes and a real estate development plot that will leave countless non-Jews homeless, to build a compound upstate where the Sassovs can form a new voting bloc to “rewrite the political realities of their new congressional district.” (I’m getting shades of a community like Monsey, complete with the troubling commentary that springs up in its school board meetings.)

The relocation plan is thought of, with affinity, by its architect as a “literal web” of kickbacks and connections, because likening Jews to scheming spiders has always been a great thing for our people! Just ask this cartoon of Svengali! Or these ones from the collections at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum!

The Sassov conspiracy, we learn in the novel’s acknowledgments, was adapted from a TV project Mansbach was developing, and it’s a concept that is dripping with a disdain for Haredi Jews that rubs off even on casual descriptions. One Hasidic supernumerary is said to speak English that rolls off the tongue with “all the grace of two drunks trying to exit a bar at the same time.” As for a relatively handsome Sassover, he is observed as moving with “a grace and confidence Miri had seldom seen in a Hasid. It filled her with an unexpected rush of pride, or perhaps some heretofore undiscovered species of platonic lust. Weird.” Yes, weird!

The Hasidic mob subplot is but one unnecessary snag in a story that brings The Golem face-to-face with neo-Nazi protesters in Kentucky, who are seeking to save the statue of a racist judge from the 19th century. (Other odd interludes include an Airbnb real estate scam; the out-of-nowhere appearance of Bigfoot; and the insertion of a blank verse poem about white Jewish privilege that misunderstands when Jews became white in America, the factors that broke up the Black-Jewish Alliance and fancifully claims that Mel Gibson schmoozes over latkes with the ADL while Jesse Jackson remains a pariah for his “hymietown” remark.)

At the crux of the story is the question of how Jews should confront those who want us dead — whether the brute force intervention of The Golem is desirable or, in fact, beneath our people’s pursuit of tikkun olam, the main Jewish concept Len is familiar with. But it’s a question that’s buried beneath a heap of unneeded incident and clumsy prose.

Mansbach’s wit, which delivered an amusing if too-cute-by-half novelty in his adult children’s books and collaborations with Alan Zweibel and Dave Barry, is spread thin by an idea that is maybe worth the length of a short story. The book’s tone is not equal to its attempts at gravitas; Mansbach as narrator undercuts his own grim recounting of Jewish persecution with a bone-dry “LOL.”

When he tries to deliver moments of distress, he often gives us something biochemical: an “epinephrine-soaked overload”; “clarity slicing through the surge of catecholamines cascading into his nervous system like like a bodysurfer diving through a breaking wave”; “a kind of benign curiosity that, to Miri’s astonishment, instantly caused her central nervous system to cease its wartime production of adrenaline, epinephrine, and cortisol.”

If that all sounds oddly clinical or detached, it points to a deeper flaw. The fear undergirding the book is not really felt. The immediacy of the torch-brandishing bigots in Kentucky is an abstraction and The Golem encountering them just a fun little conceit, or a deus ex machina to be reconsidered along the lines of the punching Nazis debate.

When The Golem insists he should only be activated in a moment of crisis, his new creator is at first hard-pressed to find one as a non-visible Jew in Brooklyn.

“There’s a lot of handwringing about intermarriage,” Len offers. “Israel-Palestine is a f—g shit show. Most people try not to bring it up. Um… I know more and more Jewish couples who definitely do not want to circumcise if they have boys…”

It’s hard to see Mansbach, as easily distracted as he is from his own premise, as less ambivalent than his protagonist, even if he frames his doubts as thoughtful and admits that white supremacist cops and Camp Auschwitz merch are real.

Mansbach isn’t sure that we are at an inflection point — the first in the novel’s mythos since the Holocaust — to pull our old earthen ace out of retirement. (If he asked an actual Brooklyn Hasid, whose everyday threat of violence is almost nowhere alluded to, I’m sure he’d hear more about the urgency.)

One can’t escape the suspicion that our creator doesn’t know why he made a golem, other than that it might be nice to have.