A reunion project for Holocaust survivors and their families runs a race against time

The Nazis destroyed families and their histories — a pair of genealogists is trying to put the pieces back together

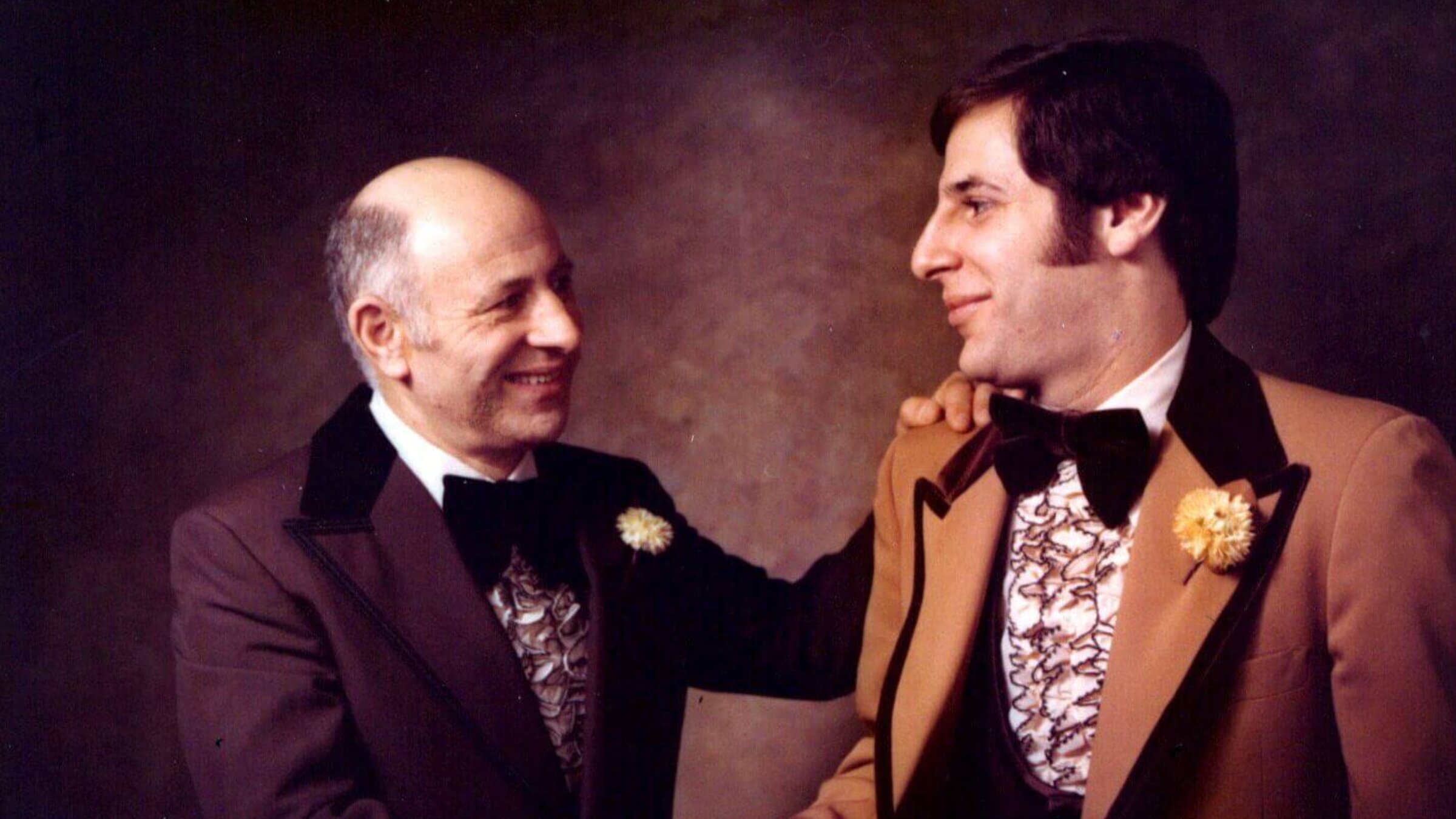

Mark Steinbock on his wedding day with his father, 1975. Until recently, for Mark, his father’s family history had been something of a mystery. Courtesy of Mark Steinbock

Growing up outside of Cleveland, 71-year-old Mark Steinbock, a retired lawyer and accountant, knew little about his father’s family. “My entire life, I had been told that he had no living relatives,” Steinbock told me.

Steinbock’s father, Mendel, was born in Demblin, Poland, in 1918 and survived the Holocaust. From a Displaced Persons Camp in Germany after the war, he searched for his eight brothers and sisters through the Red Cross, and decades later looked again for any relative through the US Holocaust Memorial Museum when it opened in the 1990s.

After Mendel died in 2016, Mark grew curious about his roots. “There was going to come a day when one or more of my grandchildren would come to me and say, ‘Tell me a little bit about our family,’ and the fact of the matter is, I knew next to nothing.”

Then in the winter of 2022, Mark’s son shared with him a Facebook post about the DNA Reunion Project, a pilot program through the Center for Jewish History which supplied Holocaust survivors and their children with free DNA kits. The project, co-founded by the Center and genealogists Jennifer Mendelsohn and Adina Newman, aimed to find lost branches of Jewish family trees and uncover ancestral stories buried in the Holocaust.

The initiative recently relaunched as an independent organization called the Holocaust Reunion Project. With children survivors reaching old age, they’re in a race against time.

As is the case with most people, Mark’s DNA test results produced a long list of potential second and third cousins around the globe. Seemingly, these individuals with whom he shared less than 2%t DNA didn’t bring him any closer to learning about his grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins who were victims of Nazism. But then, he said, “Jennifer and Adina did their thing.”

The two specialize in taking the galaxy of data points of distant relatives and finding constellations of relatives. They painstakingly recreate genealogical trees and piece together narratives. “They helped me immensely open up a chapter of my life that for 70 years I didn’t think existed,” said Steinbock.

A knack for genealogy

Mendelsohn, a former freelance journalist, created a name for herself during the Trump administration by tweeting out the family immigration stories of anti-immigrant politicians. “You complain about chain migration, I reserve the right to do your tree,” she warned politicians in a 2018 tweet.

Before she began wielding genealogy as a political bludgeon, she got her start after innocently poking around on Ancestry.com in 2013. “I happened to be in the car with my husband’s 95-year-old survivor grandmother,” she told me during a Zoom call from her home in Baltimore. Her husband’s grandmother Frieda told her she had two aunts who immigrated to Chicago before World War I, then lost touch with family in Poland.

Mendelsohn discovered she had a knack for research, and tracked down Frieda’s American relatives on the genealogy website. “I introduced her to three first cousins. And it just was an incredibly powerful experience for everybody,” she said.

“They had family photographs, because their mothers emigrated long before the Holocaust, and they had family mementos,” Mendelsohn said. “Those things for survivors can be so, so precious.”

Genocide, she explained, does not just victimize individuals, but also decimates communities and family histories. “We do our little part however much we can to push back against that,” Mendelsohn said, “ to reconnect these families that were severed and give them back the history that was stolen from them.”

She’s not the first in her family to feel the genealogy calling. Her brother Daniel Mendelsohn, a humanities professor at Bard, wrote the 2006 NY Times bestseller The Lost: A Search for Six in Six Million, which investigated the stories of relatives murdered in the Holocaust. Much of his research was conducted through mailing in document requests and finding relatives and contacts through word of mouth as he traveled the globe.

Since then, many archival documents have become instantly accessible online. Advances in commercial DNA testing have also further boosted genealogy research.

“You land on the right DNA spot and it zooms you up,” Jenifer Mendelsohn explained. “You’re turbo boosted to the next level, because it just makes immediate connections between people.”

It’s become possible to discover family histories that once seemed unknowable.

Newman discovered the power of the DNA website 23 and Me to reshape family histories in 2018 when the website matched her with a partially ethnically Jewish cousin. With the help of the Facebook group DNA Detectives and many hours of dogged research, she uncovered an 80-year-old secret of a new uncle.

“So we have this whole new branch of the family,” she said over Zoom from her home in Boston, adding that learning of these new relatives has been a blessing.

Jewish DNA is different

Both Newman and Mendelsohn employ DNA genealogical techniques that adoptees and others use to solve unknown parentage cases, but what sets them apart is they are experts on eastern and central European Jewish genealogy.

“Jewish DNA is, well, different from other DNA.” Mendelsohn explained in her Medium article, “No, You Don’t Really Have 7,900 4th Cousins.” DNA companies predict relationships based on shared DNA between two individuals. Jews, however, long lived in geographically limited areas and married within their community; genealogists call this an “endogamous” population. Two different Ashkenazi Jews will often share several distant relatives in different places in their tree, which confuses the matching algorithms.

“Jews share much more DNA with each other than average, which grossly inflates our relationship predictions,” explained Mendelsohn – this makes untangling Jewish DNA results that much harder.

The other challenge is tracing lineage back to prewar Europe. “There’s this very self-defeating attitude with Jewish genealogy,” said Mendelsohn, “and particularly with people affected by the Holocaust: ‘there’s nothing left to find.’

The pair of researchers can often pinpoint the Russia empire shtetl where a family originated, and despite myths that all records were destroyed by the Nazis even dig up old world family documents.

In 2021, Mendelsohn wrote in the Washington Post about being approached by the family of a child survivor found in a post-war Polish orphanage. She discovered the woman, Sarit, was not an orphan but was separated from her parents in the chaos of war. Almost 80 years later, Mendelsohn helped orchestrate a family reunion in Israel between Sarit’s daughter and her elderly aunts.

The following year, Mendelsohn and Newman researched the ancestry of Jackie Young, an 80-year-old retired London cab driver. Young knew he was born to a Viennese Jewish woman deported in 1942, but not who his father was.

Having survived as an orphaned infant in the Theresienstadt ghetto, Young long assumed his father must have been a Nazi who protected him. Newman and Mendelsohn, however, discovered the identity of his father, a Jew, and connected him with relatives.

“We specialize in those cases of hidden children and babies smuggled out of ghettos,” Newman told me.

Now almost 80 years after the war’s end, the two do outreach to synagogues and senior centers where they try to dispel myths about privacy issues related to DNA testing. Their goal is to reach survivors before it’s too late.

Through the Holocaust Reunion Project, he filled in his father’s genealogical tree with hundreds of relatives, learning the names of the family members who died in the Holocaust. He also discovered that his father’s uncle, aunt and cousins survived.

A second-cousin in France confirmed that family who left Poland in the 1930s made it through the war relatively unscathed in the south of France.

“My father would have been delighted at the prospect that he was wrong, that certain of his relatives actually did survive,” said Steinbock, “but the war ended in 1945 and it wasn’t until over 75 years later that these discoveries were made.”

“It’s bittersweet,” he reflected. “I wish I had known about these people when I was growing up.”