Sitting shiva for his wife, an overcaffeinated academic is scalded by grief

Mark Haber’s ‘Lesser Ruins’ brews a potent mix of Montaigne’s ‘Essays’ and electronic house music

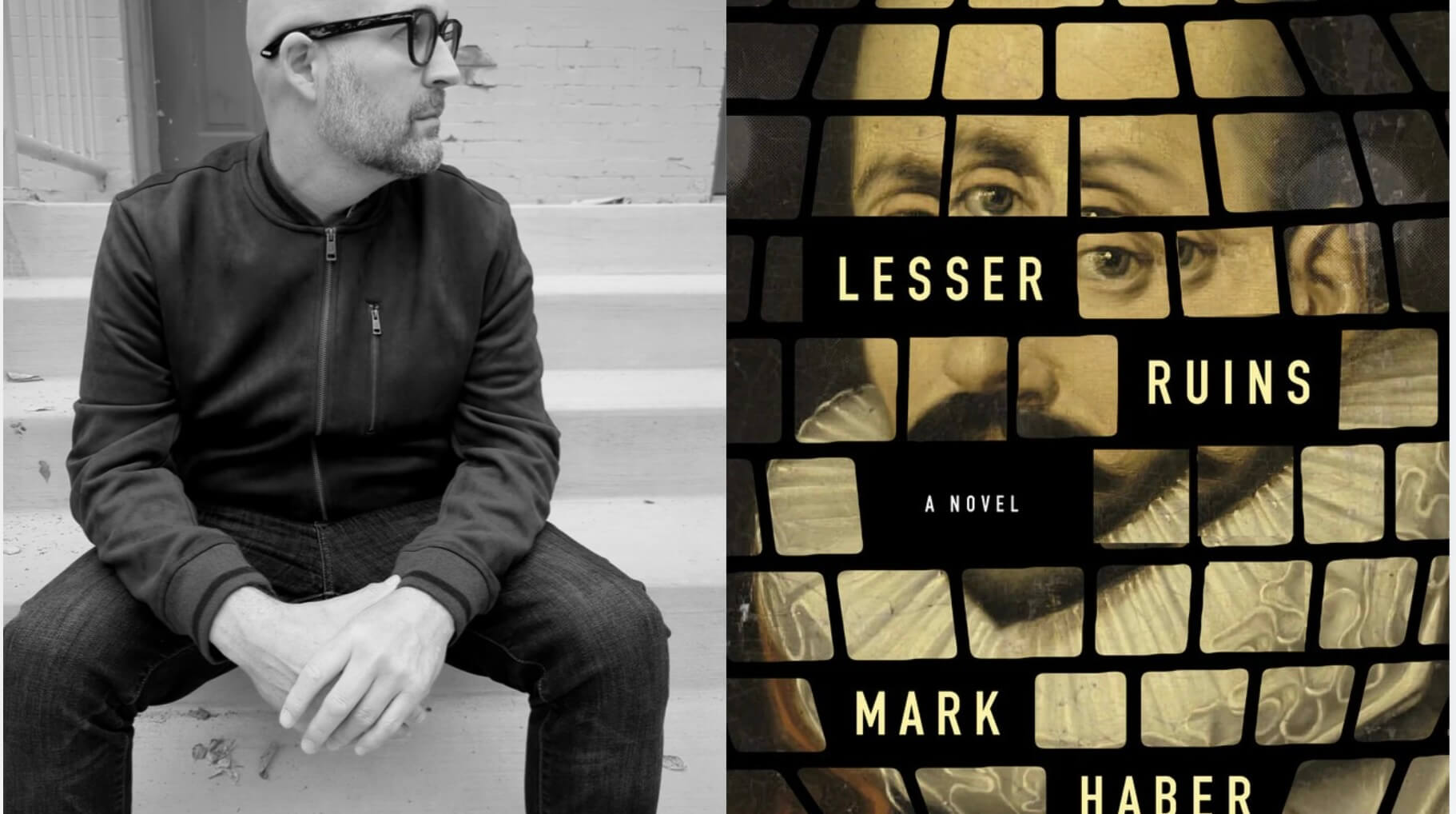

Mark Haber’s latest book is ‘Lesser Ruins.’ Courtesy of Coffee House Press

Lesser Ruins

By Mark Haber

Coffee House Press, 296 pages, $18

The genius move that transformed Ricky Gervais from a slightly needy, moderately funny, sketch comedian into a major star on both sides of the Atlantic was the way he took his strengths and flaws and amplified both, using a sitcom context to both condemn a caricature of himself and also free that caricature up to be hilarious. Writing his on-stage persona into middle manager David Brent, and throwing Brent into an office in a mockumentary split Gervais’ worse traits off from his best reflections and did so to brilliant comic — and sympathetic — effect.

Mark Haber achieves a similar transformative feat in his new novel, Lesser Ruins. Haber takes a limited, annoying (unnamed) narrator — who is nevertheless well read enough to be fascinating and perceptive enough to acutely, if defensively, perceive his own limitations — and transcends his character’s personal and professional limitations to provide a breathtaking series of recursive, swelling digressions on grief, art, history and coffee.

Perhaps not since Camus opened The Stranger with “Today, Mommy died. Or yesterday, perhaps, I don’t know.” has a novel opened effectively with such a startlingly callous announcement of the death of a family member. Haber’s Lesser Ruins begins:

“Anyway, I think, she’s dead, and though I loved her, I now have both the time and freedom to write my essay on Montaigne…”

Like Camus, much of what follows in the novel is packed into this seemingly careless opening. The “Anyway” buttonholes the reader to tell them a story. “I think” perfectly foreshadows the interposition of thought between the death of his wife that is too close to properly acknowledge (he constantly explicitly avoids her closet which is redolent of her) and the idée fixe of his book-length essay on Montaigne — the father of the essay — which will elevate him out of mediocrity. My ellipsis indicates that the opening breath extends to a half-page sentence that begins one of several unbroken, paragraph-less “chapters” which are stream-of-consciousness rants to the reader.

Actually, to be more specific, the address to the reader is less like a literary stream of consciousness and more like an extended voicemail, like the ones from his son Marcel against which he rails and ignores as interruptions. That complaint is merely part of a larger complaint about the modern world and the idiocy of “smartphones” whose “chirps” constantly interrupt the narrator’s “mental saharas.” Counter-intuitively “mental saharas” becomes one of his repeated phrases of regret. Rather than arid, lifeless moments, he welcomes these desert states of mind as expanses where the slow thought necessary to produce true art or scholarship can take place.

One particular voice mail — which the narrator never finishes listening to — is about ten minutes long. In it, he tells us, Marcel — a musician and devotee of electronic house music — describes how a perfect house music track is, likewise, ten minutes long. And Marcel continues to explain a number of the characteristics of a perfect track. While evincing not one iota of self-consciousness from the narrator (though scads from the author), both the message itself and also the description of the message embody a number of the traits that Marcel attributes to the perfect house music mix: samples, pace, repetition, themes.

Not just on this occasion, but regularly, readers of Lesser Ruins are guided to understand the novel using Marcel’s opinions on electronic music as criteria. It is difficult, in fact, not to do so when the artistry discussed in musical creation so clearly describes the literary creation facing the reader. One track is described as “a journey as well as a fable” that “swells and unfurls, collecting details the way an avalanche or landslide collects pebbles and soil as it charges down a mountain.” The three breathless, breakless, spaceless sections of about 90 pages each are indeed coffee-fuelled charges down an emotional mountain as the narrator slouches about his dim home in his yellow padded slippers.

The narrator drinks an alarming amount of coffee but it is not just his addiction that is harmful to him, so is the gleaming, chrome, expensive, heavy Nuova Simonelli coffee maker that he has illegally installed under the classroom desk in his room at the Community College (a room with portraits of Montaigne on each of the four walls). It ends up severely burning him in what will be the terminating event in his teaching career. Typically for a book where stupidity and lack of achievement are constantly at the forefront of the narrator’s attention, someone mistakenly triggers the fire alarm; in the melee, rather than help him, two students film him on their smartphones, cursing and wounded.

One feature of the novel is the recurring phrases, like “mental saharas” or “I retired, or was fired, depending on who you ask.” As with the samples in Marcel’s house music, the phrases are not simply repeated, but are modulated, tweaked, replayed in different ways given different contexts. The narrator also italicizes words and phrases to give them color or emphasis, or to indicate annoyance, as is the case with the permanent italics for “smartphone.”

This is Haber’s third novel. His 2019 debut novel, Reinhardt’s Garden, was named on the longlist for the PEN/Hemingway Award and his 2022 Saint Sebastian’s Abyss was one of the New York Public Library’s best books of 2022. Like W. G. Sebald, who Haber’s narrator mentions, there’s a seamless mix of erudition and fiction. For example, while publicizing Reinhardt’s Garden, Haber wrote about an entirely plausible, but invented, author to whom he claimed to owe a debt — Mila Menendez Krause. The Menendez Krause doppelganger in the book seems to be an older sculptor named Kleist who was a neighbor of his at the Horner Institute.

In one climactic episode during a storm when the narrator has run out of coffee, he and Kleist are celebrating the completion of her masterful series of sculptures, Die Stiefel der Dummheit (which she translates as The Boots of Idiots). Her instant coffee, masterful sculpture, and deep history as the child of Holocaust survivors are all of explicit and lengthily explored fascination to the narrator. These sculptures are intended to fulfill the work that Polish Jewish artists were unable to complete because they were murdered by the Nazis who were scared of the power of art. He tells us she told him they were

“a collection of sculptures never created because the wholesale slaughter of those Polish sculptors, works conceived in her imagination and sculpted by her own hands but, in essence, made by those murdered Polish Jews, Jews collected and killed at the hands of men with anesthetized souls, men frightened by the possibility and expanse of art…”

In his famous maxim Walter Pater said that “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music.” But he continues, “in all other kinds of art it is possible to distinguish the matter from the form, and the understanding can always make this distinction, yet it is the constant effort of art to obliterate it.” As Haber’s narrator charges down the mountain, impelled by grief and coffee (but loath to discuss the former) he obliterates the sources of his content, dispersing anecdotes and analyses from Marcel, his wife, Director Pleva of the Horner Institute, Kleist the sculptor and more.

Talking at us during the period of shiva but after the rabbi, mourners and his son have all left him alone in the home, the narrator spills the pebbles of information he has collected — about wigs and perruquiers, about dueling poets and duels, and, appropriately for a novel published by Coffee House Press, about varieties of coffee beans, their introduction into Europe and how Kafka and various French intellectuals adopted them.

The novel’s jumps in register from grandiose to trivial, from historic to contingent and from irascible to inconsolable are frequent and affecting. There’s a deep comic strain to the book but also a tragic one. The accident with the coffee machine is absurd but also disastrous; the epic bombast of the prose is delivered by a man walking around in yellow slippers but his wife has just died after years of dementia.

The tumbling fulminations of the grieving widower — he has a digression on that word, “widower,” too — repeat themselves, head off on tangents and then weave across each other. The topics seem to be different only to resemble one another as he rambles, not only art and coffee, not only his book-length essay and Marcel’s music, but himself and Marcel; himself and Montaigne; Kleist and the narrator’s wife; Bogota and Berlin to where Marcel might move; Mexico and Austria that Kleist searingly compares to the detriment of the latter. These and more are compared and contrasted not in a Hegelian way, but in the manner of Four Tet – Marcel’s favorite band (a real one) – in a danceable, listenable way unlike other genres.

In George Eliot’s Middlemarch, Dorothea (the hero) marries Edward Casaubon, an aging academic who constantly fails to write his “Key To All Mythologies,” just as Haber’s narrator fails to write his Montaigne book-length essay. Dorothea has fallen in love with the idea of his ideas, but the reality is that the well of thought has dried up. He dies and frees Dorothea up to marry the dashing young Will Ladislaw. But if, instead, Dorothea had died and Casaubon had sat down with time and freedom and copious amounts of caffeine, to write his “Key” it might have sounded like Lesser Ruins.