How a son of Holocaust survivors joined a commune and helped to free ‘Hurricane’ Carter

Compassion for the underdog has been a constant theme in the life of Sam Chaiton

Commune members Sam Chaiton and Terry Swinton with Rubin “Hurricane” Carter outside the commune’s mansion in the King City section of Toronto. Courtesy of Sam Chaiton

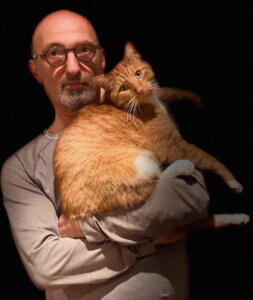

Sam Chaiton’s new memoir, We Used to Dream of Freedom, has two seemingly unrelated narratives: the trauma of growing up as the child of Holocaust survivors, and the battle to free Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, the boxer who served close to 20 years in a New Jersey prison for a crime he didn’t commit. Chaiton, a 74-year-old Toronto author and playwright, had a bird’s eye view of both storylines.

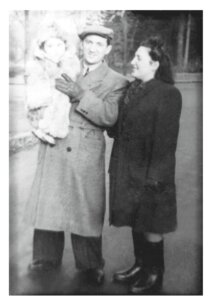

His parents, Rachmil and Luba Chaiton, grew up in Wierzbnik, Poland, and emigrated to Canada in 1948. And, after a judge overturned Hurricane Carter’s conviction for a 1966 triple homicide in Paterson, NJ, Carter moved to Canada and joined the Canadian commune where Chaiton lived for nearly 50 years.

“That the trajectory of my parents’ lives was scarily similar to Rubin’s is clearer to me in retrospect,” Chaiton writes, citing the “unjustness of their incarceration based entirely on racism rather than reason.”

In Chaiton’s account, liberation didn’t seem to bring happiness — either for his parents or for Carter. But all were still able to carve out meaningful lives for themselves. The Chaitons raised five sons, three of whom became lawyers. Carter co-founded an advocacy group in Toronto that won the release of other wrongfully convicted people. But as an elder of one of Canada’s First Nations’ people told Chaiton’s commune, “The day you get out of prison is the day your sentence begins.”

Obviously a believer

Though his parents wanted him to be a doctor, Sam Chaiton decided to focus on language and literature “Hitler couldn’t kill me, but you could,” his mother told him.

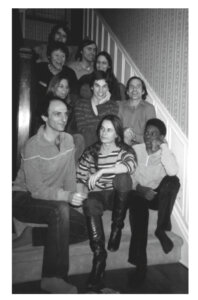

He became a dancer and fell in with a group of Torontonians who were caught up in the countercultural spirit of the late 1960’s and early 70’s. They lived collectively but abhorred the term commune.

The collective stayed intact for a half-century. One of the last of its longtime members, Terry Swinton, passed away earlier this year. Though the group may have rejected mainstream culture and its values, it sure didn’t abstain from capitalism. It started three successful businesses involving house renovation, selling hats for the hip-hop crowd and importing batik garments from Malaysia. At one point, they operated the Five Believers Batik retail stores in Toronto, Palm Beach, Florida and Long Island. The store took its name from the Bob Dylan song, “Obviously Five Believers.”

Over the decades, the commune bought or rented mansions in some of Toronto’s toniest neighborhoods. And it spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on Rubin Carter’s case during the 1980’s. At one point three members, including Chaiton, moved to New Jersey to work full-time on the court case as investigators and paralegals.

An authorized biography of Carter noted that when his lawyers tried to thank them in court papers, they declined the mention. Lazarus and the Hurricane, a best-selling account of their involvement in the legal saga by Chaiton and Swinton that was published in 1991, was written in the third person.

After appeals by the prosecution had been exhausted and Carter’s legal struggles were finally over in 1989, the former boxer went back to Toronto with the Canadians and was romantically involved with one of the women in the commune. Chaiton refers to the collective as his chosen family.

Family secrets

For Chaiton, growing up in the shadow of his parents’ Holocaust trauma was a more painful affair. They refused to speak to their sons about what happened to them in Europe, though it was something they openly discussed with the fellow survivors who comprised their social network in Toronto.

“Freg nisht!” (Don’t ask!),” Luba Chaiton would say when her sons pressed for details about her experiences in the Shoah.

As for his father, Sam Chaiton writes that he was afraid of him. Rachmil Chaiton served as the Gestapo’s tailor before he was sent to a slave labor camp.

“He was certainly the disciplinarian in the household, and he was not averse to using his belt or the back of the hand when he was so moved,” Sam Chaiton writes.

His response was to flee. He disappeared from the lives of his parents and brothers in 1973, and never saw his parents again. They died in a 1985 car accident. His brothers tried desperately to find him after the car crash but failed. Chaiton didn’t reach out to his brothers when he got news of the tragedy. Abe Chaiton, his eldest brother, didn’t realize until he read the new memoir that Sam was aware of the parents’ passing soon after their deaths.

“I was shocked, absolutely blown away by that,” Abe Chaiton told me. “It took a long time, a very long time to forgive him.”

In explaining his decision to cut off all contact with his parents, Sam summons Tevye, the fictional dairyman in Fiddler on the Roof who disowned one of his children for marrying a Gentile.

“If a Jewish parent can excommunicate their offspring, the reverse can also hold true,” he writes. “Whenever I was in their presence, I would look into their eyes and all I could see was disappointment. I needed to end the harm being done to myself and to them. The only way I saw out of this irreconcilable conflict was to absent myself from it.”

Abe Chaiton told me that the family feared Sam was part of a cult and couldn’t escape, but they knew he was still alive because Toronto police informed his father that Sam kept renewing his driver’s license every three years.

After the death of their parents, the four brothers learned a shocking family secret, that both their mother and father had been previously married in Poland. Not only had their spouses been murdered, but their children were, too. Luba Chaiton, it turned out, had witnessed her daughter’s murder.

It wasn’t until 1991 — nearly two decades since he had last seen them — that Sam re-connected with his brothers and learned about his parents’ traumatic backstory. He gasped at the realization that his disappearance was all the more painful for a mother and father who, given what happened to them during the Holocaust, forever worried about losing their kids.

A compassionate life

At home, the Chaitons spoke Polish amongst themselves and Yiddish to their sons.

“Rachmones (meaning compassion) had to be one of the first Yiddish words that I learned,” Sam told me over the phone. He and his brothers were taught to have rachmones for the underdog, a lesson that eventually led to his role in helping Hurricane Carter as well as helping to found the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted, now known as Innocence Canada.

Chaiton and the others in the commune mentored several young Rwandans in Toronto, three of whom were genocide survivors. Some of the Rwandans lived with them, others worked at Big It Up, the commune’s hip-hop headwear company.

Chaiton went on to write Noah’s Great Rainbow, a play about a Rwandan genocide survivor who worked at a nursing home taking care of a Holocaust survivor. The nursing home in the play was based partly on Toronto’s Baycrest Centre, an elder care facility where a large number of Holocaust survivors have resided over the years. The caregiver in the play was inspired by a Rwandan survivor named Sharangabo who was close to Chaiton and the commune. The play’s Holocaust survivor was a retired tailor like Chaiton’s father.

‘I think we were in a cult’

The commune where Chaiton lived had its share of success stories — for example, Lesra Martin, who as a teenager brought the commune into the Hurricane Carter case, is now a civil litigator in British Columbia.

“Sam was my salvation,” Martin, now 61, told me. “I owe him hugely for my life, the success that I’ve had academically, professionally, and as a husband and a father, none of which would’ve been possible had it not been for Sam coming into my life.”

But Martin said he has mixed feelings about the commune as a whole.

He said he “escaped from the household” because of its “our way or the highway” mindset. He recalled that when he got out of law school and started working as a prosecutor, Carter and members of the commune gave him grief.

“They saw my work as being the work of the devil, having gone over to the dark side,” he recalled with a hearty laugh. “I was not very welcome by the house in general at the time.”

Martin confirmed that the commune discouraged its members from having contact with their families, which was first reported more than 20 years ago in James S. Hirsch’s biography Hurricane: The Miraculous Journey of Rubin Carter. For that book, Hirsch spoke to former members who said that Lisa Peters, who was at the center of the group, was a charismatic tyrant and something of a control freak. They told Hirsch that for most of the time Rubin Carter was part of the household, someone escorted him every time he left the house.

Rory Angus Sinclair was part of the group for 18 years. He became disillusioned with it and decided to leave. He was quoted in a front-page story in The Toronto Globe and Mail about the “brutal nature of life inside the commune.”

“I think we were in a cult,” Sinclair told me. “I wouldn’t have used that word living there but it’s certainly become clear to me that we fit into that [definition].”

A legacy of sadness

Chaiton’s brother Abe “gobbled up” books and films about World War II but until he learned about his parents’ specific losses during the Shoah, Sam Chaiton never read books or watched films about the Holocaust, in fact, never searched for documentary evidence about his parents.

At an opening in Toronto featuring works by an artist who was reportedly obsessed with Wierzbnik, the town in Poland where his parents lived, Chaiton learned that his father was quoted in a scholarly study about the slave labor camp they were sent to and also testified in the war crimes trial of a Nazi who was accused — but ultimately acquitted — of supervising the liquidation of the Wierzbnik ghetto in late October 1942. Scores of Jews were murdered on the spot. Thousands of others were sent to Treblinka or slave labor camps.

Chaiton also found out that his parents made an unsuccessful attempt to escape from a slave labor camp in Starachowice.

All this information transformed the way he came to view his parents. Now, looking back, Chaiton has a different take on their refusal to talk to their kids about the Shoah.

“I know silence is not an unusual response to severe trauma,” he told me. “They were building a new life in Canada and that’s what they wanted to focus on, rather than the old history, the pain, the suffering.”

Now, after writing the memoir, he looks at Rachmil Chaiton as a mensch, as someone he can be proud of.

“I feel that it’s brought me a closeness to my parents that I never felt while they were alive,” he told me, “and the same with my brothers.”

In the epilogue to the memoir Sam Chaiton writes that, in part, the book is an apologia to his brothers. His closest brother, David, wrote a scathing letter when Sam re-surfaced in his brother’s lives.

“You should never think, even for a moment, that your departure from the family and your repudiation of our parents did not irrevocably alter their universe,” he wrote in the letter.

Eventually, they reconciled. When Sam told his brother that he was studying Yiddish and was sad that their parents weren’t around to converse with him in the mother tongue, David replied: “Sadness is a legacy of our upbringing. It travels with us always.”