It was one of the strangest Jewish records ever made — good luck finding a way to listen to it

Avant-garde stalwart Lionel Ziprin once said his grandfather, Rabbi Nuftali Zvi Margolies, could sing better than Enrico Caruso

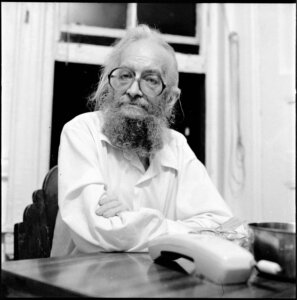

In his New York Times obituary, Lionel Ziprin was called the “Mystic of the Lower East Side.” Photo by Jon Kalish

The new Harry Smith show at the Whitney Museum surveying the work of the painter, filmmaker and folklorist includes an LP made from Smith’s recordings of a prominent Lower East Side rabbi in the 1950s. Like so much of Smith’s oeuvre, the LP is inaccessible. Visitors to the Whitney won’t be able to read the label on the vinyl disc because it’s been placed too high on the wall. If you wanted to listen to it, you’d have to go to the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

The record, Prayers and Chants, was never widely distributed by Folkways Records and is a reminder of one of the more colorful, ill-fated chapters of Jewish culture in the 20th century. It was a condensed version of a mid-century boxed set of sorts that consisted of 15 LPs in a loose-leaf-like binder produced from hundreds of hours of recordings Smith made over a period of two years.

The singing and Yiddish storytelling on the LPs was the work of the late Rabbi Nuftali Zvi Margolies, who met Smith through his grandson, Lionel Ziprin, also deceased.

A puzzle from top to bottom

A penniless Harry Smith had shown up on Ziprin’s doorstep in the early 1950s. Ziprin was a veteran of Lower Manhattan’s avant-garde art scene and counterculture, and shared many passions with Smith, including a fondness for mind- and body-altering substances, the study of esoteric mystical traditions and a curiosity about beings in outer space.

Smith has often been referred to as a polymath. Much of his collections — which included records, string figures, paper airplanes and blood-stained tattoo bandages — has gone missing. Many of Smith’s paintings and films have been lost, stolen, given away, thrown in the trash, traded in lieu of rent or destroyed by the artist himself. The only remains of the stunning paintings Smith did interpreting specific jazz recordings are on color slides made by a fellow painter. The rabbi’s recordings, which Ziprin wanted to preserve and disseminate, have met a similar fate but were salvaged. Their fate remains uncertain.

In his new Harry Smith biography Cosmic Scholar, John Szwed chronicles Smith and Ziprin’s relationship.

“The guy’s a puzzle from top to bottom,” Szwed said of Smith. “He was his own worst enemy, that’s for sure.”

Decades of research

Last week, Szwed attended a reception at the Whitney along with Ziprin’s daughter Zia; Rani Singh, director of the Harry Smith Archives; and Carol Bove, a Brooklyn artist who helped curate the show and is safeguarding the Lionel Ziprin Archive.

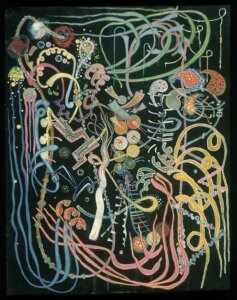

The Whitney’s Harry Smith show was 10 years in the making, according to Elisabeth Sussman, a Whitney curator who worked on it. Her interest in Smith was reinvigorated by a 2013 exhibit at the Maccarone Gallery in Manhattan that featured industrial designs made by a company Lionel Ziprin started in the 1960s. Harry Smith contributed work to the designs, which Ziprin had hoped to print on Mylar so they could be attached to tile, linoleum, wood and other materials. The business didn’t work out. The Maccarone show rekindled Sussman’s interest in Smith, who she remembered from a 1995 Whitney show on the Beats.

That Maccarone show was curated by Bove and Philip Smith, a Berkeley-based rare book seller who said he has been obsessively researching Smith for 30 years.

Smith also illustrated greeting cards for Inkweed Studios, a company run by Ziprin and his wife Joanne. A study by Smith for one of the greeting cards is displayed on the wall at the Whitney below the Prayers and Chants LP. Also on that wall: a print of a Smith painting titled The Tree of Life in the Four Winds. The Tree of Life is a diagram used in Kabbalah and other mystical traditions.

When Harry met Ziprin

When Smith sought out Ziprin, it was at the suggestion of a mutual friend who suggested Ziprin as a teacher of Kabbalah and Tibetan Buddhism. Ziprin was known for having a substantial background in Judaic Kabbalah among other esoteric spiritual disciplines. According to Bove, Ziprin taught Jewish mysticism to a number of avant-garde artists outside New York. A full-page obituary in The New York Times referred to Ziprin as the “Mystic of the Lower East Side” and went on to describe him as “a self-created planet.”

That particular “planet” was apparently expecting visitors from other planets. The backyard of the Ziprin family brownstone in the East Village during the 1960s had a landing strip in case extraterrestrials decided to drop in.

While Ziprin and Smith shared an interest in UFOs, they were also obsessed with angels, which Ziprin said he had seen since childhood. Around 2005, when I interviewed Ziprin in his apartment at the Grand Street co-ops, he told me Reb Shimon Bar Yochai, the 2nd-century rabbi who is said to have received the divine revelations that formed the basis of the Zohar, “teaches now in the Garden of Eden.”

Ziprin’s great mission was to preserve and disseminate his grandfather’s recordings. But before he died in 2009, he squelched offers by John Zorn, the Idelsohn Society, a Minnesota publisher of spoken-word content and a wealthy California businessman connected to some rabbis contemplating a peyote ritual with Native Americans. (Both Ziprin and Smith were fond of peyote back in the days when it was legal and the U.S. Department of Agriculture would sell it via mail order.)

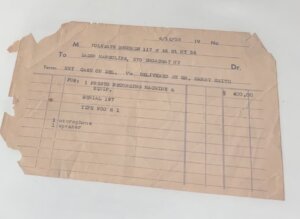

Cosmic Scholar recounts how Smith turned the rabbi’s study at The Home of the Sages of Israel into a recording studio with equipment the rabbi’s family bought from Folkway Records. It was Moe Asch, the son of the great Yiddish writer Sholem Asch, who ran Folkways at the time and commissioned Smith to put together the seminal Anthology of American Folk Music, which was released in 1952, two years before the rabbi’s LPs were pressed. The anthology is considered by many to be Smith’s greatest accomplishment and is credited with influencing everyone from Bob Dylan to the Grateful Dead.

There was some mystery about how Smith was able to communicate with the rabbi during the two years he spent recording in the Lower East Side yeshiva because Rabbi Margolies didn’t speak English. Szwed’s biography hints that because Smith knew some Latin, Hebrew, German and medieval French, he managed to have rudimentary conversations with the rabbi.

Ziprin attached Abulafia to his grandfather’s name in order to give props to the fact that one of his ancestors was the famed 13th-century Kabbalist Abraham Abulafia. As a result, a radio documentary on the saga of Smith’s recordings was titled Rabbi Abulafia’s Boxed Set.

Smith was clearly fascinated by many religious traditions. As a teenager in Washington state he gained extraordinary access to and recorded Native American ceremonies. As an adult he preached at a Black Pentecostal church that welcomed white pilgrims. Later, Smith studied Christian Kabbalah, an interpretation of Kabbalistic texts in support of Christian dogma.

In New York, though, many people assumed Harry Smith was Jewish, because he looked like “a little rabbi” with a beard and the thick lenses on his eyeglasses. Ziprin’s grandfather came to the conclusion that Smith must’ve been Jewish in a previous life.

Eventually, Ziprin became fed up with Smith and told his grandfather that Smith was an antisemite. Yet, after Smith’s passing in 1991, Ziprin had a brass plaque installed on the wall of his grandfather’s synagogue so kaddish could be recited on the occasion of Smith’s yahrzeit.

Have you seen the comic books?

Though Smith and Ziprin were quite cantankerous and difficult, Smith brought it to a whole other level. He managed to live in New York for 36 years without holding a job and almost never paid rent. For most of his life Smith had what author John Szwed refers to as “radically narrowed food preferences.” At one point he ate nothing but casaba melon, at another he had an all-dairy diet. Toward the end, Smith’s health was so precarious that he developed dental abscesses that caused huge pockets of infection in his skull. He died in a Greenwich Village hospital from bleeding ulcers and cardiac arrest.

Lionel Ziprin spent the last 30 years of his life as an Orthodox Jew in a Lower East Side yeshiva studying the holy texts with a group of Hasidic Holocaust survivors bused in from Brooklyn. On the day I visited the run-down yeshiva on East Broadway, Ziprin, who suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and needed oxygen 21 hours a day, told me that his grandfather had appeared to him in a dream and told him to go study there.

“I think he’s unquestionably a genius, literarily speaking,” said Philip Smith (no relation to Harry Smith), who in 2017 edited Songs for Schizoid Siblings, a collection of verse that Ziprin wrote in the 1950s. “Have you seen the comic books? Some of those are insane and no one really knows about them.”

The comic books, which one of Ziprin’s admirers described as having deep spirituality, were written for Dell Comics in the early 1960s. Some, which Ziprin gave a mystical tilt, featured a caveman named Kona who saved a family from monsters and giant animals. Others dealt with World War II combat.

Better than Caruso

But it’s his grandfather’s recordings that Lionel Ziprin really wanted to get out into the world. Authorities on Jewish music who have listened to the fruits of the rabbi’s improbable collaboration with Harry Smith say his singing style is a wonderful goulash with Ashkenazic, Sephardic and Arabic flavors. Ziprin said his grandfather’s voice was better than the opera singer Enrico Caruso.

Zia Ziprin, one of Lionel’s daughters, has been carrying on with the difficult work of trying to get some portion of the recordings released; various deals have been in the works over the years, but to date, all of them have fallen through. The U.K. publisher Strange Attractor Press had planned to publish a book described by its co-editor Michael Abolafia (also a distant relation) as a visual journey through the Ziprin archives, but according to Mark Pilkington, who runs the publishing house, those plans have also been scrapped.

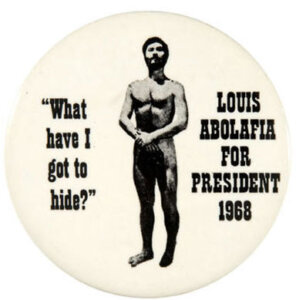

(In case you were wondering whether the Ziprin/Abulafia story could get any more wacky, consider this: Michael Abolafia had a great uncle named Louis Abolafia whose 15 minutes of fame came from his 1968 presidential campaign running for the Nudist Party on the “Love Ticket.” He appeared in posters and buttons standing naked with a hat covering his genitals and the headline, “What have I got to hide?”)

The history of the Ziprin family’s efforts to release the rabbi’s recordings ranges from wacky to tragic. Lionel Ziprin once squelched a deal by insisting that e-commerce orders of his grandfather’s CDs be suspended on Shabbos.

Meanwhile, Zia Ziprin told me she hopes to have both the book about her family and her great-grandfather’s recordings released at some point in 2024 to mark the 70th anniversary of the original release of the 15 LPs. A new web site, theziprins.com, detailing the Lower East Side family is in the process of launching.

“If my grandfather’s voice wants to be heard, it will find its way into the world with everyone who should hear it,” Ziprin told me before he died. “They have a destiny. I don’t know the destiny of these records.”

The exhibit Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith, runs through Jan. 28 at the Whitney Museum.