The crucial Bob Dylan question that ‘A Complete Unknown’ fails to answer

A ballad of a thin biopic starring Timothée Chalamet as Dylan

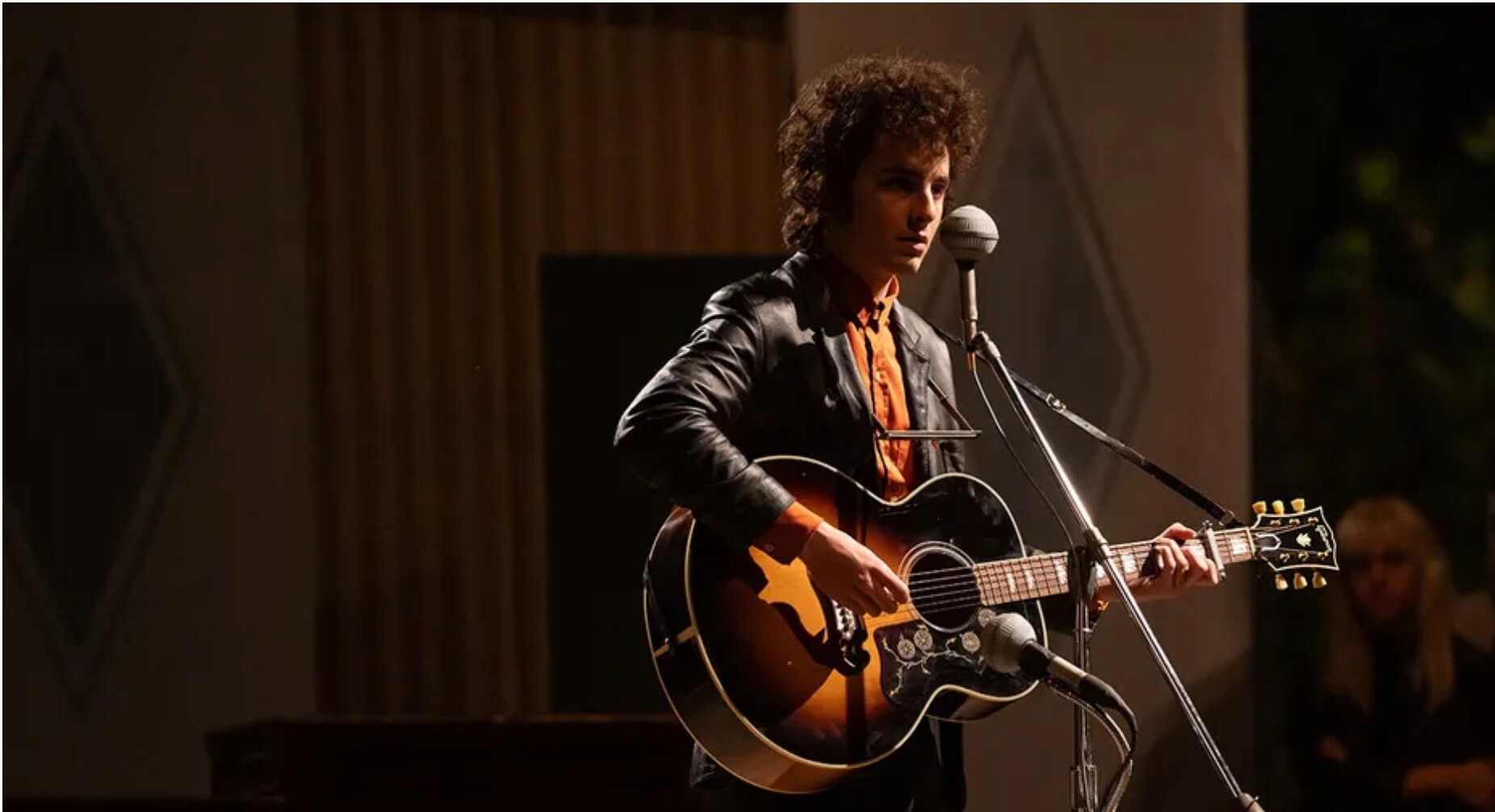

Timothée Chalamet is Bob Dylan in ‘A Complete Unknown.’ Photo by Searchlight Pictures

Why?

That is the question I hoped would be answered by a screening of the new Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, written and directed by James Mangold and starring Timothée Chalamet as Dylan.

Why make a conventional Hollywood biopic of the four years of Dylan’s life from the time he arrived in New York City as a 20-year-old college dropout in 1961 through his rapid rise to fame in the folk music world, before (mostly) forsaking acoustic music for the electric sounds of rock ‘n’ roll?

And of equal importance to why is how? How does one relate this complex story which has already been told and retold numerous times in countless books, memoirs, documentaries, films and TV shows, to say nothing of in Dylan’s songs (and books and movies) themselves — in the form of a dramatic movie intended not for hardcore Dylan fans and acolytes but for the masses, presumably drawn to theaters out of mere curiosity about a musician who in one way or another has dominated the cultural landscape for over 60 years, or simply to see the latest film featuring Chalamet, the hot young actor best known for his roles in the Dune films.

Seeing the film certainly answers the question of how. Mangold chose to go the mainstream route, offering a superficial, simplified gloss on this remarkable story, by focusing as much (or maybe even more) on some of the key characters who interacted with the young Dylan (based on real historical figures such as Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie and Joan Baez) and composites (a politically-minded girlfriend here called Sylvie Russo, partly based on the real-life Suze Rotolo), playing fast and loose with the facts in order to shape an unruly reality, along the way toward capturing the rebellious excitement Dylan elicited, first as the author of incisive protest songs drawn from daily headlines and then as an imaginative song-poet, painting his imagery in more abstract terms and giving them an added musical kick by exchanging acoustic for electric guitars.

The Beatles, after all, were blowin’ in the wind soon after Dylan penned that anthem, and Dylan was not immune to their appeal. (The Beatles and Dylan met early on — during the movie’s time frame, but this episode is omitted — and formed something of a mutual adoration society, with John Lennon adopting Dylan’s sound and writing style for a number of his mid-1960s songs and with George Harrison and Dylan bonding in a lifelong friendship that included multiple musical collaborations.)

Dylan himself had led several rock bands back in his hometown of Hibbing, Minn., and worshipped at the altar of Little Richard and Buddy Holly (just like the Beatles did). While his adoption of the rock aesthetic may have shocked hardcore folk and acoustic-music fans (and the folk-music establishment figures at the annual Newport Folk Festivals who proved as censorious as the gatekeepers of the mainstream media against whom they often struggled), it was inevitable that Dylan would find his way back to his own musical roots. Dylan’s first single, “Mixed-Up Confusion” — recorded in November 1962 — was, after all, a rock song recorded with an electric band. (Not that you would learn this from A Complete Unknown).

Pity poor Timothée Chalamet. While his well-hyped portrayal of Dylan has the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences already engraving his name on a Best Actor trophy — and while he acquits himself well in his musical impersonations of Dylan — in the end his was a thankless task, given no help from Mangold and Jay Cocks’ somewhat pedestrian screenplay. Chalamet’s portrayal of Dylan is monochromatic, consisting almost exclusively of a heavy-lidded, quiet, brooding countenance. Anyone familiar with Dylan’s appearances at the time, via taped interviews and early concert films, knows that Dylan was a highly expressive personality, full of humor and playfulness (such as when he appeared at a press conference holding a giant inflatable light bulb, which he explained with the aphorism, “Keep a good head and always carry a light bulb”) as well as occasional frustration and scorn.

Other than in multiple shots capturing Chalamet/Dylan frantically writing song lyrics at all hours of the night, the Dylan we see in the movie is largely a cipher, a naif upon whom others project their emotions or musical expectations. Chalamet gives us a bottled-up Dylan with almost no affect; what little sense we get about Dylan as human being is revealed almost entirely in the inordinate closeups of his interlocutors’ faces. Even in the performance scenes, there is little of Dylan’s giddy, antic quality or the charisma that is plain to see in Murray Lerner’s excellent 2007 documentary, The Other Side of the Mirror: Bob Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival, consisting exclusively of scenes of Dylan performing at Newport in 1963, 1964 and 1965. Dylan’s impossible genius bursts forth from the screen in those performances, leaving the viewer slackjawed at his precision, his prolificacy and his intensity — all of which are lacking in Chalamet’s portrayal.

Instead, we are treated to an entirely fictional duet performance with Joan Baez in which Dylan gets so frustrated by his partner (for reasons unclear) that he throws a tantrum right in front of the audience, all but telling Baez to fuck off before storming off the stage mid-concert. I understand the need to create new scenes in order to move the story along, but this scene is so totally out of character one fears it will leave hundreds of thousands of viewers thinking Dylan was an unrepentant asshole (which he may well have been, but not for the reasons shown in the film).

We get the how, as unsatisfactory as it may be, but the original question remains: Why? This question takes on even more relevance after seeing the film, given its disappointing lack of vision and the overall inertness of Chalamet’s portrayal of Dylan. And this may simply be owing to a fundamental flaw in the approach.

The best Dylan films — films about Dylan, films featuring Dylan playing Dylan or someone very similar, and films made by Dylan himself (he has an extensive filmography as an actor, writer, and director worth checking out) — tackle this most unconventional artist using techniques befitting their subject. There are the cinema verité documentaries Dont Look Back and Eat the Document that blend fly-on-the-wall camera work with a knowing point of view, similar or the same as Dylan’s point of view.

There are the films written and/or directed by Dylan himself, including the four-hour experimental “tour documentary” Renaldo and Clara (featuring the real-life Joan Baez along with Dylan’s then-wife, Sara, who gets no mention in A Complete Unknown even though their relationship began in the film’s timeframe) and the 2003 experimental feature Masked and Anonymous. Larry Charles, the director of the latter film, said, “I wanted to make a Bob Dylan movie that was like a Bob Dylan song. One with a lot of layers, that had a lot of poetry, that had a lot of surrealism and was ambiguous and hard to figure out, like a puzzle.” It was that approach that also made a creative success out of 2007’s I’m Not There, directed by Todd Haynes and featuring six different actors — including a memorable performance by Cate Blanchett — portraying various aspects of Dylan. In its embrace of fractured ambiguity, I’m Not There was the near-perfect vehicle capturing Dylan by way of his own aesthetic.

In the new film, you get a story approximating the story. But as the title indicates and with a nod to truth in advertising, Dylan, in the end, remains a complete unknown.