How one Jewish geneticist turned a family tragedy into a lifesaving mission.

American Heart Month is an appropriate time to learn how genetic testing can protect your family.

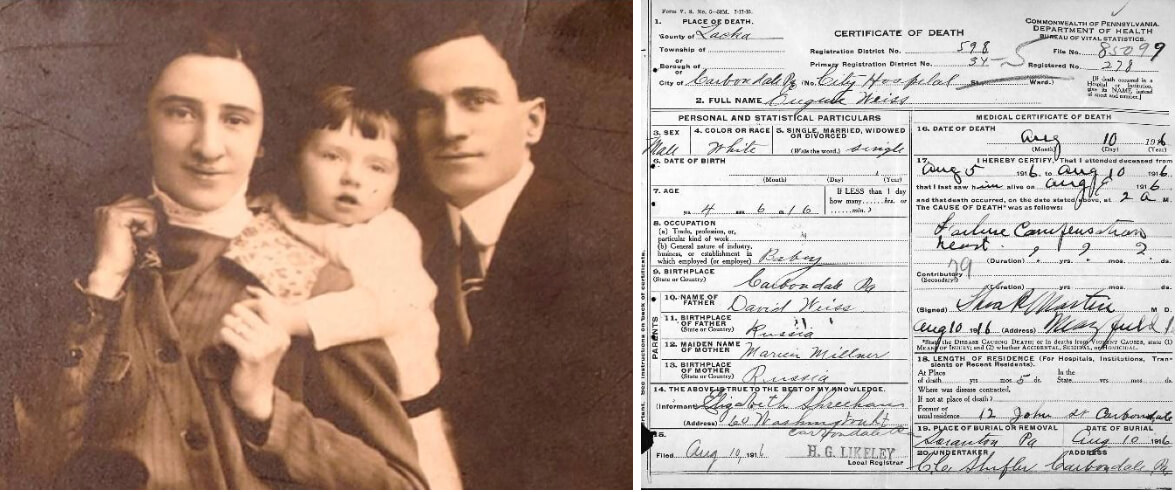

The author’s grandparents with their first child, Eugene. Despite claims that he died after being crushed by a mirror, his death certificate reveals that he died of heart failure. Courtesy of Susan Weiss Liebman

Editor’s note: This essay was adapted from “The Dressmaker’s Mirror,” a new book about sudden death and Ashkenazi Jewish mutations.

In Jewish communities, conversations about genetic risks often focus on BRCA mutations and breast cancer. But this American Heart Month, it’s time to spotlight another critical risk: genetic heart disease.

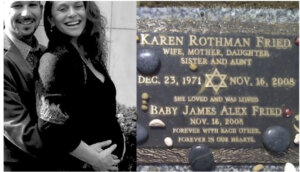

My niece was 36, six months pregnant with her first child, and newly married when she suddenly collapsed and died. The autopsy revealed she had dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), the same heart condition her mother, my sister, had been battling for years. For my sister, the condition was dismissed as a fluke caused by a virus. But after my niece’s death, it became painfully clear that our family carried a hidden genetic threat.

As a geneticist, I knew the odds: Ashkenazi Jews (AJs) are more likely to carry specific mutations linked to disease, from Tay-Sachs to BRCA. But this tragedy forced me to confront those risks on a personal level. Could my children — or I — be next?

Hunting the killer

I consulted Dr. Elizabeth McNally, director of the Center for Genetic Medicine at Northwestern University, who confirmed that my sister likely carried a mutation (genetic variant) that she passed to her daughter. Dr. McNally sent my sister’s DNA for genetic testing, but it didn’t have mutations in any of the known DCM genes. Furthermore, we didn’t know whether the mutation came from my mother, father, or arose spontaneously in my sister.

McNally advised that my nephew, my children and I undergo regular heart screenings until we had more answers. I thought this was a reasonable plan given the unknowns. But my husband worried it would discourage our children from having babies. He viewed the tragedy as a freak event that we should forget.

In the end, we compromised: I shared the medical advice with our children once, but didn’t speak of it again. My daughter followed through, but my son did not.

Dr. McNally continued testing my sister’s DNA as scientists discovered new DCM-related genes, but she didn’t find any hits. Finally, advances in genetic technology allowed her to sequence all my sister’s genes for $50,000, a fraction of the original billion-dollar price tag, with the costs covered by grant funding.

The investment paid off: McNally found a mutation in the FLNC gene, linked to heart muscle function. This led her to write a paper proposing that mutations in FLNC cause DCM. Later, more evidence from many other laboratories supported this and showed that mutations in FLNC are a common cause of DCM.

Centuries-old genetic root

I was relieved to test negative for the mutation.

My negative result was consistent with the idea that the mutation arose spontaneously in my sister. But, a few years later, another research group found two DCM patients with the same FLNC mutation as my sister. Surprised, I reached out to one of the authors, Dr. Michael Arad of the Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Israel. He told me that these patients were AJs, like my sister.

I then consulted a genetic database and found that 1 in 800 AJs have this specific mutation, but other groups didn’t have it! This meant that the mutation wasn’t new — it had been in the Ashkenazi Jewish population for centuries.

Alas, when my grandparents fled persecution in Europe, they brought more than their religion and culture with them — they also brought their genes.

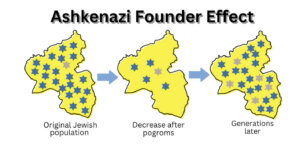

Like other Ashkenazi “founder” mutations, the Ashkenazi FLNC mutation points to our shared genetic history. Founder mutations arise because small groups that are geographically or culturally isolated allow for the chance concentration of individuals with rare mutations. Once this occurs, the group’s isolation causes many descendants to inherit the rare mutations.

Other populations also experience founder effects, for example, French Canadians who underwent a period of cultural isolation, and the Finnish who were geographically isolated in Finland.

My Ashkenazi ancestors lived in Central and Eastern Europe. They descended from a 10th-century Jewish diaspora community that settled in the Rhineland in Germany. Today, most Ashkenazim live in the United States or Israel. We are 11 million strong, about 80% of the world’s Jews.

Pogroms periodically led to drastic reductions in our size, called “bottlenecks” by population geneticists. Dr. Shai Carmi, professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem told me, “There’s a consistent picture across most papers of a bottleneck occurring around the second half of the Middle Ages, of effective size in the hundreds/low thousands.” By “effective” he means reproductively active. Since cultural isolation restricted marriage outside the group, mutations that were present then are overrepresented in modern day AJs.

As a result, AJs have about 200 known founder mutations. Most are “recessive” and only lead to disease if mutated genes are inherited from both parents. This includes Tay-Sachs, a disease we’ve nearly eliminated through widespread genetic screening.

Unlike the success with recessive mutations, we need to do more to address risks posed by dominant mutations.

For dominant mutations, only a single mutated gene inherited from either parent increases the risk of disease. Dominant Ashkenazi founder mutations exist in, e.g. BRCA1/2, which elevate risk for breast and ovarian cancers, and LRRK2 which is linked to Parkinson’s disease. The FLNC mutation in my family is another example, with potentially thousands of AJs unknowingly carrying it today.

Family secrets and heartbreak

In my family, this mutation left a trail of devastation — but it wasn’t always obvious. A story passed down from my grandparents claimed my uncle died at four years old when a heavy dressmaker’s mirror fell on him. Decades later, I unearthed his death certificate. Cause of death: heart failure, an end stage symptom of DCM. It is likely that my grandparents fabricated the mirror story to protect the marriage prospects of their surviving children.

This pattern of silence is common. Many families don’t realize genetic conditions are lurking until tragedy strikes. Even when symptoms appear, misinformation abounds. A doctor incorrectly reassured my son he wasn’t at risk because I showed no signs of DCM. He didn’t realize I could carry the mutation without ever developing symptoms.

The power of knowing

Thanks to advances in genetic testing, family members who inherit the FLNC mutation can take proactive steps, like regular heart screenings and medication. Those without it have peace of mind.

Yet, genetic testing remains underused. Nearly half of all U.S. cardiomyopathy cases are genetic, but only 1% of patients get tested. Misconceptions about cost and utility persist, even as testing prices have dropped to under $250, and genetic counseling is more accessible than ever.

Testing saves families from further loss. It’s not just about managing risk—it’s about empowerment. Knowing your genetic makeup is as essential as monitoring cholesterol or blood pressure.

A call to action

As we enter an era of personalized medicine, genetic screening offers unprecedented opportunities to prevent disease. But we need to break the silence and stigma surrounding genetic risk—especially in Jewish communities.

This February, honor American Heart Month by starting a conversation with your family. If you’re Ashkenazi Jewish, consider genetic testing — not just for cancer but for heart disease and other conditions.

The life you save might be your own — or someone you love.