The Jewish artist who almost died exploring the Wild West

Carvalho documented a dangerous expedition to California in the days of Manifest Destiny

The only surviving picture from Carvahlo’s doomed expedition, of a tepee. Courtesy of The Library of Congress

The Jewish-American community is deeply intertwined with the history of its country, often in ways that reflect the preoccupations of a given historical moment. Take, for instance, the fascinating story of Solomon Nunes Carvalho (1815-1897), a Jewish artist who recorded a revealing chapter of American expansionism in his 1857 book, Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West.

Incidents is a fascinating account of an America still teeming with vast, unexplored spaces and natural life. It’s also illuminating for what Carvalho puts in the book (about Native Americans and Mormons) and what he leaves out (any mention of Jews), illustrating, perhaps, how its author both did and did not feel fully part of the American project.

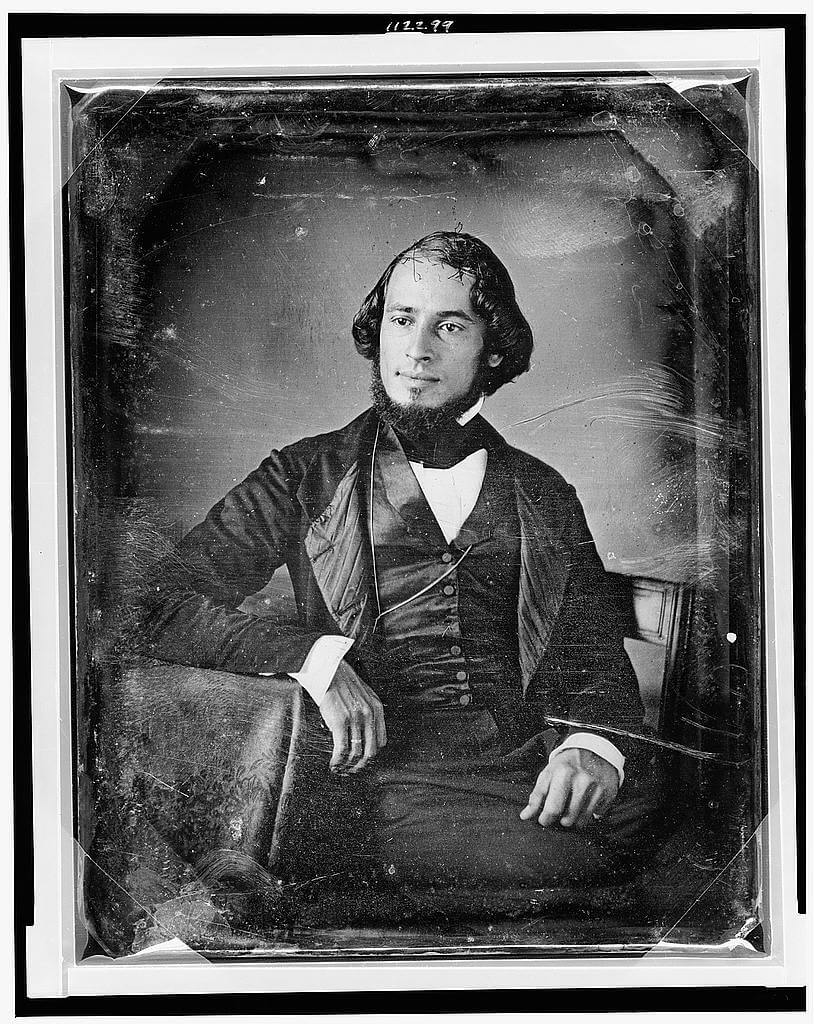

The story of how a city-dwelling Jewish artist became an explorer begins in August of 1953, when John C. Fremont met Carvalho in New York City. Carvalho, a painter and photographer with a studio in Baltimore, was in New York to demonstrate a new varnishing process for daguerreotypes, the first photography process available to the general public. Fremont was in New York preparing for his fifth expedition to the American West, this time to test the viability of a railroad line from St. Louis to San Francisco.

Fremont asked Carvalho, already a well-known portraitist, landscape painter and photographer, to come along and document the journey. Originally from the Sephardi enclave of Charleston, South Carolina, Carvalho had a wife, children and a business in Baltimore, and yet he readily accepted Fremont’s offer. Maybe he saw it as an opportunity to make his own name on a national scale, or perhaps to test the limits of his art. (Either way, one wonders what his wife, Sarah, had to say about him vanishing on a journey that would, eventually, take five punishing months; Carvalho was gone from the fall 1853 until the spring of 1854.)

By the time Carvalho met Fremont, the latter was already famous, a veteran of the Mexican-American War and a former senator from the new state of California — its first senator, in fact, from the state’s founding in 1850. He was a proponent of the Manifest Destiny, the idea that the entire North American continent belonged to the United States — not to the European powers, and definitely not to the indigenous people who already lived there. (On a previous expedition Fremont and his men massacred Native Americans, which frontier legend Kit Carson described as “a perfect butchery.”) Fremont wanted Carvalho to produce images of the new frontier to inspire Americans to venture out into the “new” territories.

The daguerreotype process, which requires cumbersome equipment and complicated chemical treatments, now seems far too complicated to be useful on an expedition. But in its day, it was revolutionary. It brought a new level of detail to photography, and it made portraits available to almost everyone, not merely those wealthy enough to commission a professional artist. Though trained as a painter, in the pattern of entrepreneurial Jews who embrace new markets, Carvalho had found success in the new medium.

Carvahlo, in other words, had little experience with the kind of adventure Fremont was undertaking. Which makes Incidents not only a fascinating account of the immense challenges and deprivations of the journey — on foot, horseback, and mule from present-day Kansas to California, over the Great Plains, a desert and two mountain chains — but also a humorous account of his own shortcomings.

The artist readily admits he is “unqualified” to wash his own clothes and to saddle his own horse, much less handle a weapon — at one point he uses his shotgun as a walking stuck and loses his revolver when they break camp. On collecting firewood, he writes: “I am afraid I shall make a poor hand in using the axe; first, I have not the physical strength, and secondly, I do not know how.” But he was, at least, courageous: Carvahlo regularly put himself in danger to get his images, venturing up mountainsides and through dicey terrain.

Carvalho is a charming narrator. But he also reflected the limitations of his time. The book is full of condescending descriptions of the Native Americans the group encountered — though Carvalho admired the “Delaware chiefs” the expedition included as guides, writing that “a more noble set of Indians I never saw,” he also includes an arrogant passage about o the “squaws” of a Cheyenne village, who, he writes, believed him “more than human” thanks to his photography and his ability to produce fire with the flick of a match.

But he’s far more respectful of another minority group: the Latter-day Saints, who Carvalho spent several weeks with in their settlement of Parowan, Utah. The expedition had nearly perished crossing the Wasatch Mountains in February of 1854 — one member died, “his feet frozen black to his ankles.” The group was so close to starvation that they had to vow not to eat each other (which had possibly happened on a previous Fremont-led expedition) after eating their mules and horses. They barely made it to Parowan, leaving behind most of their supplies, including the daguerreotype equipment.

When they arrived, Carvalho was so malnourished he needed weeks to recover. The expedition pressed on without him, leaving the artist to observe and write about the Latter-day Saints at length.

In the 1850s, Mormonism was only a few decades old and was distrusted, at best, by many Americans, due to its practice of polygamy and its reputation for violence. But the adherents of this new American religion fascinated Carvalho, who was impressed by their comportment and industry. He got to know Brigham Young quite well — apparently, he was a good dancer, demonstrating a “light fantastic toe.” Carvalho received admirable hospitality as they helped him recover and eventually reach California. And although the artist took a pretty dim view of polygamy, calling it “destructive to society, and to all human progress,” he was so taken by the group that he even reproduced several Mormon texts at the end of his book.

It seems possible to me that Carvalho wanted to ease his countrymen’s fears about this new religion, perhaps because he, as a Jew, was a member of a mistrusted minority religion as well. Yet this leads us to one of the strangest things in this remarkable book: Carvalho does not mention that he’s Jewish. There is one moment when he eschews porcupine because it resembles pork, and one can almost hear him whispering the shekhinah, the prayer for moments of awe, when describing the incredible natural abundance of America: “The immense undulating prairie, teeming with buffalo, blacktail, deer, antelope, sage and prairie chickens.” But that’s all we get. Why?

The most likely possibility is that Carvalho was trying to protect Fremont, who was nominated for president by the new Republican Party in 1856. It was a time of vicious anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiment, and perhaps the artist felt his Jewishness would have tainted his friend. For all his goodwill toward the Latter-day Saints, Carvalho may have felt his Judaism was still too far outside the American mainstream. It wasn’t the only thing he left out, perhaps to guard his friend’s electoral chances: The 1850s was a time of growing tension and even violence between the supporters of slavery and abolitionists, and, whatever his many faults, Fremont was an abolitionist. Yet the words “slave” or “slavery” also do not appear in Incidents.

Although Carvalho missed the last stages of the expedition, Fremont did succeed in making it through present-day Colorado to California. But others would find it easier to actually build the transcontinental railroad through southern Wyoming, meaning the expedition turned out to be barely a footnote in American history. For all Carvalho’s careful protection of Fremont’s reputation, the latter eventually lost the presidential race to James Buchanan, and, after a period as a ineffective general in the Civil War, died, nearly penniless due to bad investments.

Carvalho was circumspect about his Judaism on the expedition. But when he returned to Baltimore, he was active in Jewish life. Towards the end of the 1860s, he decamped with his family to New York City for better business prospects, but cataracts made it impossible for him to continue as a visual artist. Instead, he turned his attention and inventiveness to steam heating. In 1866, the Scientific American reported on “Carvalho’s Apparatus for Super-Heating Steam,” a way of wringing more energy from coal. He died at 82 and is buried in New York City.

The great tragedy is that most of Carvahlo’s daguerreotypes from the expedition never saw the light of day. Fremont wanted to save publishing the images from the expedition for his own book — presumably, as the funder, he had the rights — but he never wrote the thing. And in the 1880s, fire broke out in the warehouse where the plates were stored; only one survived.

It was an incredible loss for American history, and it perhaps explains why Carvalho isn’t better-known. Which is a shame, because his account is a snapshot of the U.S. during a time of great change. And his life illustrates the possibilities opening up to American Jews in the mid-19th century — even if he didn’t want to put that in print.