Persecuted by the KGB, a Jewish master soared to new heights in the West

Born in Marc Chagall’s hometown, the Russian Jewish dancer Valery Panov has died at 87

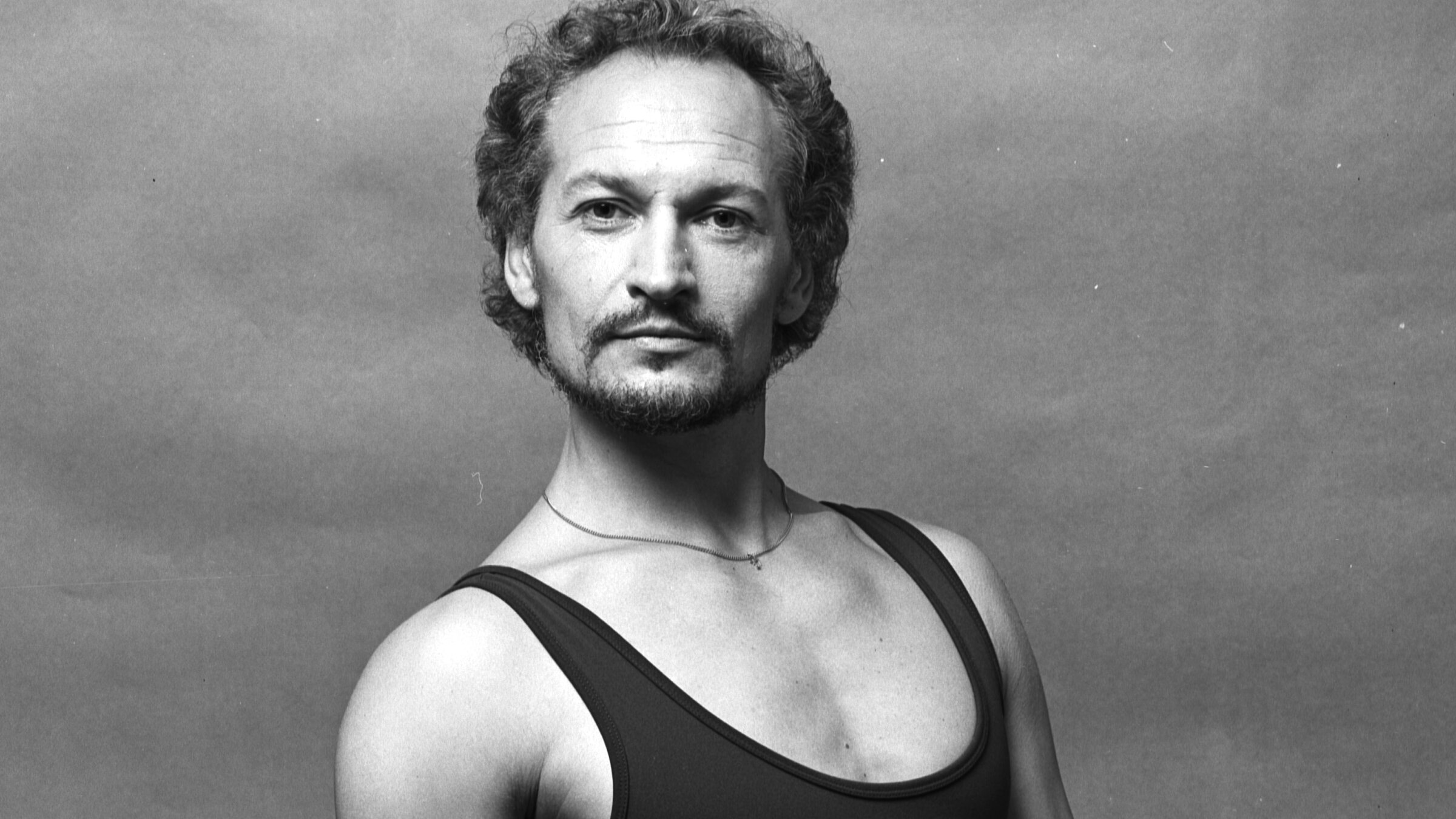

Dancer Valery Panov, October 1978. Photo by Getty Images

The Russian Jewish dancer Valery Panov, who died June 3 at age 87, proved that the torment of Soviet-era antisemitism endured long after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Born in Vitebsk, Belarus, celebrated as the hometown of the painter Marc Chagall, Panov was the son of Matvei Shulman, an industrial supervisor, who assimilated to the Communist ethos of his time. In a memoir, Panov wrote that his father “had developed into a genuine antisemite who hated all Jews, including himself.”

As a schoolboy, Panov was brought up to consider Jewish heritage as a “shameful, weakening virus.” As an aspiring young dancer, he realized that the family name Shulman “had the wrong ring for an important theater,” so after his first marriage to a dancer, Liya Panova, he adopted his wife’s typical Russian name as a “solution to the Jewish problem.”

In his early years, Panov’s artistry ranged from exceptional strength and preening solidity in such classical ballets such as Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty, in which he co-starred in 1964 with the sublime Natalia Makarova, and the tsuris-ridden eccentricities of Stravinsky’s Petroushka, which he performed in 1963.

Indeed, Panov’s Kafkaesque, persecuted incarnation of the title character inspired by Russian folk puppetry prefigured his subsequent ordeals at the hands of the KGB, the main Soviet security and intelligence agency.

Soon after these performances, his view of Judaism would be transformed by Israel’s Six-Day War of 1967. Of that conflict, Panov later observed: “Jews were defending themselves instead of cowering, [and] I recognized my relationship to the beatings they had suffered so long.”

Temporarily approved of by the state, Panov was awarded the Lenin Prize, and he was issued a passport that indicated Russian nationality instead of the much-despised Jewish identity.

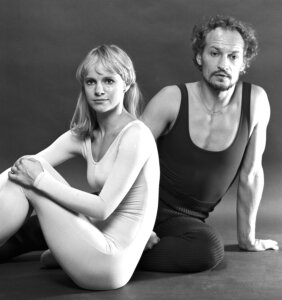

Ambitious to express himself as a dancer and choreographer in ways that were impossible in the USSR, in 1972 Panov and his second wife, the non-Jewish ballerina Galina Panova, applied to emigrate to Israel; the Communist authorities responded by firing him from the Kirov ballet, imprisoning him for ten days for “hooliganism,” and even attempting to poison him.

The situation was so fraught that even the hard-bitten American Jewish novelist Herbert Gold confessed that visiting the Panovs in their dismal Leningrad abode in 1974 evoked in him extreme tension and the “enforced calm I remember when going into combat.”

This state-sponsored ill-treatment continued for two years, but left Panov undaunted, in part due to strong support from international Jewish groups that displayed an activist solidarity rarely seen in later, more resigned decades.

In 1974, a public celebration in New York of Panov’s birthday was organized by a committee featuring Jewish arts world celebrities Barbra Streisand, director Herbert Ross, Beverly Sills, Mike Nichols, dancer Nora Kaye, actress Hermione Gingold, writer Paddy Chayefsky, Hal Prince, Theodore Bikel, and Joel Grey.

The festivities included a message from Senator Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson, a Presbyterian who so ardently supported the State of Israel and American Jews that two years later, New York Magazine would call him the “Jewish candidate” for president.

Three decades earlier, a Congressional delegation which included then-Congressman Jackson had visited the newly liberated Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany. Continuing to keep in mind the historic legacy of antisemitism, in 1974 Jackson pointed to the irony of the Panovs being persecuted “by a government which does not want them, but will not let them go.”

Jackson idealistically concluded with the hope that the couple might one day celebrate Panov’s birthday “in the free world.” Indeed, this became possible when due to a policy reversal, the Soviet Union decided to allow some high-profile Jewish dissidents to leave for Israel. Among these was Sylva Zalmanson, a human rights activist, artist and engineer who also made aliyah to Israel in 1974.

Other jailed Soviet Jews would not find freedom so swiftly. The artist Boris Penson had to wait until 1979 to be allowed to depart for Israel. And a dentist named Mark Nashpitz endured one year of “corrective labor” followed by a five-year term of exile in Siberia before finally being permitted to leave in 1985.

As for Panov, when he arrived in Israel, he declared: “I have come home.” Unlike other Russians who used Israel as a stepping stone to later careers in Europe or America, Panov maintained roots in his adopted country, eventually founding dance troupes there which hired fellow Russian emigres. He also collaborated with the well-established Batsheva and Bat-Dor dance companies.

But this faithfulness would not be without complications, tragedies and carping from some onlookers. In 1978, dance critic Marcia B. Siegel published a take-down in The Hudson Review, kvetching that Panov had been a malcontent since his earliest days as a dancer, but only latched onto Jewishness as an escape route belatedly.

This ungenerous reading of Panov’s motivations for immigration as explained in his autobiography appeared to blame the dancer for the timing of his acceptance of his roots: “Only after being kept home from tours and denied other privileges he wanted did [Panov] embrace Judaism and start boring his way out of the situation that was so oppressive to him,” Siegel charged.

Siegel’s main complaint was that Panov’s talents were overhyped, and he and Galina supposedly “distorted their modest talents in the interest of sensationalism and audience appeal.” Siegel added: “Their frankly aggressive performing style is well suited to the thrill-oriented way many people now look at ballet.”

While it is doubtless true that some of their stage appearances might have teetered on the brink of kitsch, like a Star Wars ballet danced in Los Angeles, accompanied by the LA Philharmonic led by the soundtrack composer John Williams.

But far more of Panov’s efforts showed an earnest resolve to explore Jewish history. Along with other Jewish choreographers such as Pauline Koner and Anna Sokolow, he donated documentation to The Dance Library of Israel, located in Tel Aviv at Beit Ariela, after it opened in 1975.

And in 1994 Panov created the ballet “Dreyfus— J’accuse” to music by the Russian Jewish composer Alfred Schnittke at the State Opera in Bonn, Germany. Inspired by the notorious Dreyfus affair, the turn-of-the-century French antisemitic scandal in which a French Jewish artillery officer was wrongfully convicted of treason, the theme of singling out Jews for unjust accusations was plainly still present in Panov’s mind.

The previous year, he had opened a ballet school and company in Ashdod, Israel, where he remained based. His modest organization complemented a heterodox national tradition in which there remains room for specialists in Yemenite, Moroccan, Iranian, and Kurdish Jewish dance and even flamenco.

Yet despite the satisfactions of feeling at home, Panov could not escape family grief, and in 2009, his third wife, the classical dancer Ilana Yellin-Panov, died by suicide at age 42 on the eve of a new production choreographed by Panov of Prokofiev’s Cinderella.

To survive such calamities, Panov had clearly learned fortitude during his years of oppression in the USSR. As he told Herbert Gold in 1974 while still a captive of the KGB and the Soviet state: “For a long time they frightened me, but they can’t frighten me anymore.”