In a first-of-its-kind museum, mezuzahs keep memories of pre-war Poland alive

Aleksander Prugar and Helena Czernek collect old imprints of mezuzahs to uncover Jewish history

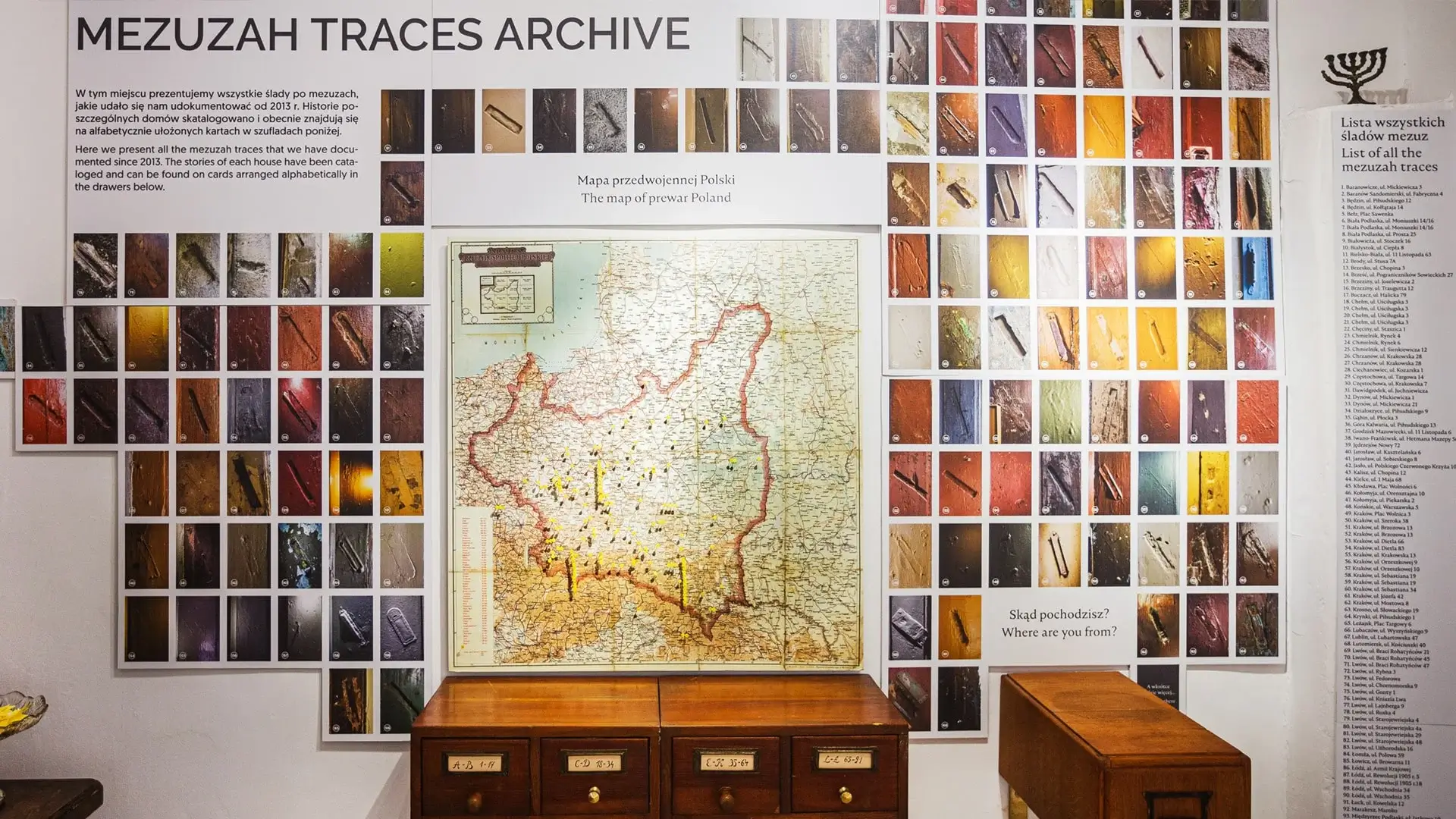

At the Mi Polin Mezuzah Center in Warsaw, Helena Czernek and Aleksander Prugar have collected and documented nearly 200 mezuzah traces. Courtesy of Mi Polin Mezuzah Center

For Helena Czernek and Aleksander Prugar, a typical work trip involves packing water bottles, clothes, silicone mix, and recording equipment into a car. With the rock band Myslovitz playing on the car stereo, they set off on a multi-day trip throughout central Poland, searching for mezuzah traces — some of the last remaining evidence of Jews having lived in parts of Poland before the war.

Almost twelve years ago, Czernerk and Prugar, who are both Polish, began researching mezuzah traces — imprints left in the wood of Jewish homes before World War II. While many contemporary American mezuzahs stick out from doorposts, in pre-war Poland, they were placed in a groove in the wood and covered with a metal plate.

Czernerk and Prugar capture the indentations with silicone, which they then use to create plaster molds. At their Mi Polin Judaica studio, they make bronze cast replicas of the original mezuzahs. On trips throughout Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus and Romania, they have collected more than 165 traces.

Their mezuzahs have been displayed all over the world. A collection of more than 30 of their mezuzahs are at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah in New York, adorning the building’s entryways. They have been displayed in museums in New York, Warsaw, Vienna and Krakow.

Mezuzah trace hunting perfectly combines Czernek’s and Prugar’s interests. Czernek studied at design schools in Warsaw and Jerusalem. In 2013, at the request of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, she created a daffodil design to commemorate the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. It is now worn by tens of thousands of people across Poland every year on the rebellion’s anniversary, April 19. Prugar, who has degrees in the social sciences and journalism, briefly studied film, focusing on documentaries.

When Czernek first came across mezuzah traces in Krakow, she saw another opportunity for an art project. Prugar saw a unique vehicle for storytelling. Both of them were interested in preserving history. Because the indentations were often carved by hand, they’re each unique.

“Every single mezuzah trace can be recognized as a fingerprint of those who made this mezuzah 100 or 130 years ago,” Prugar said. “Every single mezuzah trace is like a small particle of Polish Jewish DNA.”

I spoke with Czernek and Prugar on Zoom multiple times over the course of their weekend excursion to Szadek, Bełchatów, Pabianice, Skierniewice and Łódź. Often, as was the case with this trip, they spend a lot of time following leads from clients who want the two to check for mezuzah traces at the homes of their forebears.

“Their families left Poland before war, during the war or shortly after the war,” Prugar said. “They would like to have something that came from their second home.”

For a trip like this one, the pair spends a few days beforehand doing research on the town and its Jewish history, including documentation of former Jewish homes. Unfortunately, there is rarely any information on who the people were.

“They weren’t famous. They weren’t rich. They weren’t artists, musicians, scientists,” Prugar said. “So the mezuzah trace is the only link, the only possibility to find the history of those people and bring them back to life once again.”

Czernek and Prugar do not know exactly why some mezuzahs were embedded into the wood, as opposed to protruding off the edge of the door frame, as is the custom today. Czernek speculated that it might have been related to class: Those who couldn’t afford something pretty and made from nice material would opt to have something that retreated into the wood instead of something that stuck out. Whatever the case, the grooves have provided rare evidence of Jewish existence in places where Jews were removed en masse.

“It’s like a big adventure where I feel like we know about something that almost no one knows,” Czernek said.

The work isn’t glorious — it requires long hours on the road, sometimes staying in towns with no cell service or having to hunt for traces in the rain. The pair has fortunately never run into conflict, but still wear dark clothes and keep a low profile in new neighborhoods, not wanting to attract too much attention to themselves. Half of the time, they find nothing.

Still, Czernek described mezuzah hunting as “addicting” — anywhere she goes, if she sees buildings from the pre-war era, she stops and looks for traces. Some of these buildings are in bad shape but still carry stories of the pre-war era with them.

“There’s like two time zones in the life of mezuzah trace hunters,” Prugar said. “the present time zone and the past time zone. And when we are crossing the doors of all tenements, we are transferring ourselves into [a] past time zone and we are diving in this history.”

But as more areas in Poland have begun to modernize, these pre-war buildings are disappearing — and possible mezuzah traces with them. In at least a couple of instances, Czernek and Prugar have returned to the site of a trace only to find the building has been demolished. Occasionally, they’ll come across villages where the buildings are still intact, but any evidence that Jews once lived there has completely disappeared.

“It’s very, very hard and sad and always, for me, unbelievable when we are searching in some place where there was 70 or 80% of Jewish inhabitants and today we can’t find anything,” she said.

In 2024, they opened a museum in Warsaw to share what they’ve discovered with the public. Although most of their visitors are Jewish, a significant number of non-Jews tour the center to learn about mezuzahs.

The pair still have a lot of ground they want to cover in eastern Europe and hope to make it to Spain one day as well, to find as many mezuzah traces as they can before it’s too late.

“We[‘ve] discovered stories about love, about the Holocaust,” Prugar said. All parts, he continued, “are hidden behind mezuzah traces. They are just universal stories.”