In these stunning psalms, everything is illuminated — including the lives of King David and Thomas More

At the Morgan Library, ‘Sing a Song’ focuses on the role of psalms in medieval life and literacy

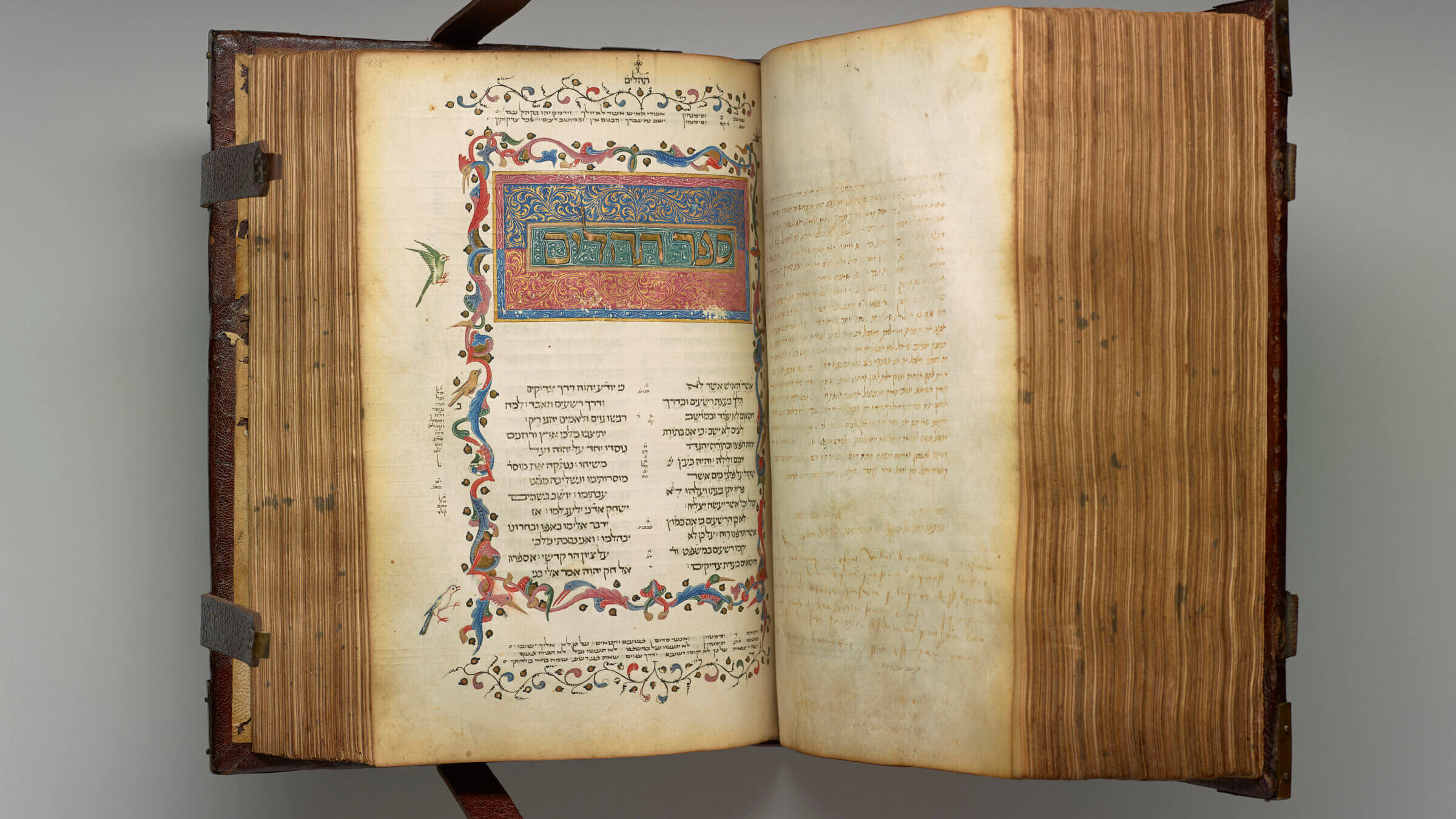

The Carcassone Bible, circa 14222. Photo by Graham S. Haber

In the center of the room, under glass, a Hebrew Bible lies open to the Book of Psalms. Gold leaf glimmers on the borders; red dragons grasp a blue shield while green and blue birds perch on curling vines.

Created for a Jewish physician in France in 1422, it is one of the treasures in the Morgan Library & Museum’s new exhibition, Sing a New Song: The Psalms in Medieval Art and Life. The show, seven years in the making, celebrates not only the beauty of the illuminated works themselves but also the lives of the people who used them.

Traditionally attributed to King David, the 150 psalms that comprise the Book of Psalms are among the most enduring texts in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. They reflect the full measure of the human emotion: from exuberance to hopelessness, from penance to protection.

The exhibit “explores the impact of psalms in medieval life, prayer, and art over then centuries.” said museum director Colin B. Bailey.

Divided into five sections — “David as Psalmist,” “Translating the Psalms,” “Illuminating the Psalms,” “Performing the Psalms” and “Using the Psalms” — the exhibition invites visitors to see psalms as living texts, not just artifacts.

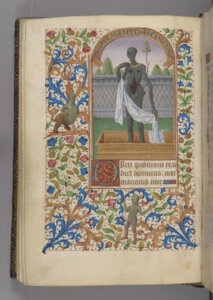

“The psalms went from cradle to grave. Children used psalms to learn how to read and pray, and when you were dying, the psalms could comfort you. The psalms even worked after you were dead because having your friends or religious people pray over you could assist you in getting out of purgatory a little bit sooner,” Roger S. Wieck, the museum’s head of Medieval Renaissance Manuscripts, said as he stood before a 15th-century painting of King David. The shimmering work shows King David dressed in a sage-green, crimson and sapphire robe, holding a golden harp; his mouth is parted, as if he’s about to sing.

While most of the artifacts here come from the medieval era, some reach back to antiquity.

A fourth-century BCE parchment fragment of a much longer literary scroll preserves three hymns relating to the New Year’s celebrations of an ancient Jewish community in southern Egypt.

As one moves through the galleries it’s clear that psalms were central to medieval literacy as well as devotion.

For example, a rare 15th-century primer commissioned for a five-year-old girl in Belgium is open to a prayer of thanks. A miniature illustration next to the enlarged text shows the unnamed girl as an adolescent, sitting down at a table, prepared to say grace.

At the time, Wieck said, there was a tradition to “bump up a child’s age” so they might envision themselves as a functioning adult.

“This is a really rare piece. There is no other manuscript that shows a layperson actually sitting down about to eat a meal to illustrate the act of saying grace,” Wieck said, adding that children’s primers “didn’t survive because they had sticky fingers all over them.”

Aside from the several “psalters” or books of psalms, on display are several lushly illuminated Books of Hours. These personal Christian prayer books contained a daily regimen of prayers and psalms patterned after monastic hours. Highly popular between the 15th and 16th century, they were often commissioned by wealthy women for their own use. The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, made for the Duchess of Guelders in 1440, is among the highlights on display.

As Wieck pointed out, psalms helped guide people through every aspect of their life, including death and dying. As such the final devotion in any Book of Hours was the Office of the Dead, a series of psalms recited to help shorten the time a loved one’s soul spent in purgatory.

Illustrations accompanying these prayers often reminded readers that death is the great equalizer. In one, a gleeful skeleton strikes a pope with a club. The illustrations in the margins continue the theme: death chases a Holy Roman emperor, a cardinal, a fleeing king, and a defiant soldier.

In another, death is rendered as a corpse standing upright in a tomb, fingering a gold necklace. The image was intended to warn its reader of the futility of wealth and ambition.

The exhibition also explores the ways both Jews and Christians deployed psalms against demons.

A series of miniature, leatherbound psalm books that once dangled from belts to ward off evil are on display. There are also a trio of incantation bowls with Aramaic inscriptions that spiral around images of demons. Bowls of this nature were sometimes inscribed with the names of those seeking protection.

“People often buried the bowls upside down in the corners of houses to protect the occupants from evil,” Wieck said.

The exhibition closes with a poignant example of psalms as a source of solace: the Prayer Book of Sir Thomas More, whose handwriting fills the margins of the book, which he kept at his side during the 18 months he spent in the Tower of London before his execution.

Although the ritual of confession is confined to Christianity, King David, the author of the majority of the Book of Psalms, is frequently portrayed in the seven penitential psalms, each of which is about asking for divine forgiveness for mortal transgressions — in large part because he committed adultery with Bathsheba and then murdered her husband Uriah.

Sing a New Song runs through Jan. 4, 2026 at The Morgan Library & Museum.