A bespectacled, Jewish hypochondriac with literary pretensions and a creepy fascination with his stepson’s girlfriend — Guess who?

Woody Allen’s debut novel ‘What’s with Baum” has been done better before — by Woody Allen

Woody Allen in Venice, 2023. Photo by Getty Images

Sign up for Forwarding the News, our essential morning briefing with trusted, nonpartisan news and analysis, curated by Senior Writer Benyamin Cohen.

What’s with Baum?

By Woody Allen

Post Hill Press, 192 pages, $29

The last Woody Allen film I saw was Blue Jasmine, which won three Academy Awards including Best Actress for Cate Blanchett and Best Screenplay for Allen. The film was released in 2013, six months before Allen’s then 28-year-old daughter, Dylan Farrow, came forward with allegations in an open letter in The New York Times, that Allen had sexually assaulted her when she was a child. This was her first time speaking publicly about a claim that her mother, Mia Farrow, had been making since 1992, after she discovered Allen had been in a sexual relationship with her daughter, Soon Yi. It was in 1992, when Allen’s 21st film, Husbands and Wives, was released in theaters that we, the public, were given a choice: Choose art and go see the film or choose morality and stop watching Woody Allen.

I, still in college, chose art. So did the public; that film sold more tickets than any of his previous films. I’m not going to beat myself up about it now, as I had been groomed by the corrosive 90s culture to pay little attention to the way women were treated by men. A few cultural gems to put you back in the moment: American Pie; Monica Lewinsky; O.J. Simpson; Girls Gone Wild; Britney Spears; Anita Hill.

I congratulated myself at the time, happy I had chosen art, because Husbands and Wives is a masterpiece of storytelling — so what if Farrow is spectacularly humiliated, as she, innocently playing Judy, the wife of the writer, Gabe Roth (played by Allen), has no idea what in reality he has done? Juliette Lewis, or Rain, is a dark-eyed, hair-twisting ingénue in Gabe’s writing class at Columbia. We learn about his feelings for her, and his wife, when he speaks to the audience in a faux-doc style that allows the central characters to share feelings and perspectives on their lives.

By 2014, when Dylan Farrow pled with the public to believe her, eight years after Allen married his wife’s daughter, whom he had helped to raise, I was long done with all that. I chose morality and I chose to believe the victim. I was done with Allen and I was done being groomed by him from the now ubiquitous presence of Mariel Hemingway, or Tracy, as Allen’s 17-year-old onscreen girlfriend in Manhattan, to Rain, with whom Gabe takes great pains to show that the more than three decades between them is normal, as she had many relationships with the “middle aged set.” But in 2014 my decision was an easy choice, right? Woody Allen hasn’t made a movie that I cared to see since that time. (The latest is 2023’s Coup de Chance, a French language film because, bien sur, the French still love him.)

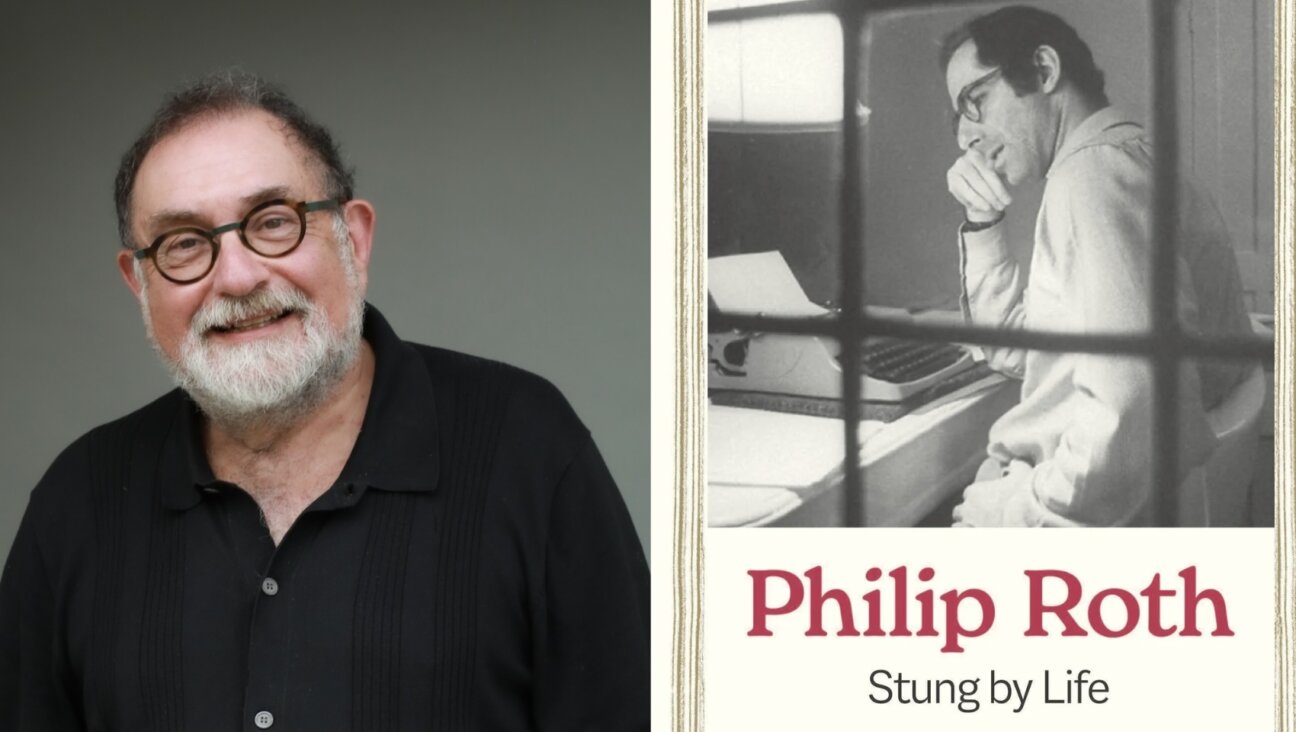

Enter Woody Allen’s debut novel, What’s with Baum?, which one has to read the same way one might now watch a semi-autobiographical Allen feature film: with skepticism, curiosity about the artist’s intent, and a constant longing for subtext. It’s significant to note that this novel by one of America’s most famous directors was not acquired by a mainstream trade publisher but by Post Hill Press. Allen’s 2020 memoir, A Propos of Nothing, was also published out of the mainstream. After workers at Hachette walked out in protest of its impending publication and when Ronan Farrow, Allen’s estranged biological son and bestselling author and journalist, left the publisher in response, the small press, Skyhorse, published it. This acquisition placed Allen alongside such literary luminaries as Melania Trump, RFK Jr., and Blake Bailey, whose biography of Philip Roth was cancelled by W.W. Norton following sexual assault allegations against its author.

Here’s the novel: Asher Baum is a writer in his 50s and he looks familiar: He’s a hypochondriac with a “Semitic” nose; his “Foster Grant black-rimmed glasses [give] him a scholarly air.” “If he were a movie actor,” Allen writes, “he would have played shrinks, teachers, scientists or writers.” He lives in the country with his wife, Connie, even though he hates the country (where to walk after dinner?) and loves Barney Greengrass, which does not exist in the country.

The novel opens with the conceit that Baum has begun to talk to himself, perhaps due to early onset dementia, a device reminiscent of the documentary style that allowed Allen to showcase his inner anxieties and break down the division between public and private in his characters. Technically, it’s also convenient to concretize feelings with words in a screenplay, as everything the viewer needs to know must be said out loud or shown visually. One of the only things that a novel as a genre has got over film is the characters’ interiority, and Allen has made the distinct choice not to use this. So why a novel? I asked myself this often while reading this pleasant debut that, had I not known who the author was, I would have found terribly derivative of Woody Allen. Which is to say, it’s been done before and so much better.

The novel putts along with Asher Baum talking to himself and we learn he has never met his potential as a writer. His wife, his third, whose son Thane has just published a novel to tremendous (if completely unrealistic) acclaim, has cooled to him. Asher believes this might be because of his failure to find success, though it also might be because of the way Baum lusts after other women, with a side of longing for his true love, his first wife, the blonde shiksa, Taylor, who returns to him in the form of Thane’s girlfriend, Sam. Whatever the case, Connie loves Thane and cares for him more than she loves and cares for Baum and while that has always been annoying to Baum, it is now unsustainable, particularly when Thane has gotten all these accolades that should be Baum’s. When Sam takes a ride with Asher into the city, the plot unravels episodically with added moments of predation, racism and misogyny, meant to be skewered or celebrated, one cannot tell. In other words, it’s creepy as hell. But it’s Woody Allen, so we’re used to it. We even, dare I say, long for it.

The thing is, this guy Baum, who references Buster Keaton, Liz Taylor and Montgomery Clift, declares his love for Cole Porter and Gershwin, writes on Olivetti typewriters and hovers over phonographs is supposed to be in his 50s. And these are all the well-known obsessions of Woody Allen, who is 89. Allen might see himself as forever in his 50s, (hey, I am forever 13) but Baum is not. And so, the novel begins to lose its authority.

When the plot thickens (ever so slightly, with lumps) the novelistic devices get messier. There’s a slippery perspective that starts close on Baum then pans out, and there’s an amateurish repetition of exposition in dialogue, another screenwriting tic. The perspective on one occasion defies logic, shifting momentarily to Connie describing her own feelings, which Baum has never tried to understand. And then there are purportedly huge moments — such as when Baum runs into that spectacular ex, Taylor, while he’s with Sam, her doppelganger — which barely leaves a mark on his consciousness or the prose.

What’s with Baum? We don’t know him because Allen has placed him at such a distance. But he wants to be known! And appreciated. He wants to feel up the “Asian” (Japanese or Chinese, her ethnicity flips at random) journalist. But with novels, the reader needs a reason to turn the page, to know what you’re reading to discover, and Baum as he exists in the woods with Connie, fearing ticks, and all his other Allenesque preoccupations isn’t reason enough. Aside from his two ex-wives and his handsome rich brother, we are also told Baum wrote a play in his youth, “A domestic drama…conflicts, psychological vulnerabilities, foibles and failures abounded alongside the lustful desires and adulterous confidences all up there on the stage for everyone to see.” Sound familiar? And yet this is the most novelistic Allen gets — we as readers are forced to do the analysis; we don’t get anything more. And here’s the other thing we don’t get: laughs. There is nothing funny about a warmed-over Woody Allen schtick, not on the page anyway.

So why a novel? Why did Woody Allen write this in this form? The notions are cinematic. Just after the climax (suffice it to say that Allen’s love of Chekhov is in evidence as the Act I gun does of course go off), Allen writes, “In a film this would be a fade-out…Go to black and then fade up weeks later.” What’s with Baum? ends like this. We never get back to what it would be if this were a novel, which, hello? it is.

The ending, which brings the reader out of the story, reminded me again of Husbands and Wives. Mia Farrow’s Judy is meek and mousy and yet through her passive aggression manages to get everything she wants. Fine. Sidney Pollack’s Jack drags his hot aerobics instructor girlfriend, also named Sam, out of a party by her hair and we are on his side. Fine. And Gabe Roth has succeeded in normalizing a relationship with Rain. Fine. For her birthday, at a party at her parents’ well-appointed Upper East Side apartment, Gabe has brought her a delicate jewelry box that, when it’s opened and the ballerina spins, plays Kurt Weill’s “It Never Was You.” (Judy Garland sang this in her final film. If you want to hear her sing it, go ahead — it will undo you.)

The song’s title foretells the film’s finale: A thunderstorm, an open window, a kiss. And then, the hook! Gabe tells Rain they can’t be in a relationship, what with her, a student, and so young! Rain is of course disappointed, but she understands. It never was you, you see. And we believe Gabe, we do, because we have always believed Woody Allen, even if we can see it now so clearly for what it is. But then, in the denouement, breaking that fourth wall, Allen tells the camera that he’s working on a new novel, which he explains is less confessional, more political. And then, astonishingly, Allen turns to the camera, looks the viewer in the eye and says, “Can I go? Is this over?”

And, with that, it was.

When I went to purchase What’s With Baum?, the bookseller wouldn’t look at me. “I’m reviewing this,” I said, by way of explanation, and she breathed out, relieved. It’s a political act to read this novel. It is not the 90s. I am no longer a college girl sitting around a seminar table hoping to one day be a writer, my professor also trying to kiss me (no stormy night, no music box, but I still have a pile of signed books, all his). Is it fair to bring up the movies? I think so — those films were brilliant and complicated and funny and they captured a time, long-gone now. A novel can also do all of those things. This one, Woody Allen’s debut, relies on what we’ve already read and seen and witnessed. But you won’t learn anything you don’t already know.