Is the movie ‘Nuremberg’ about the wrong psychiatrist?

The movie stars Rami Malek as the psychiatrist Douglas Kelley — but what about Leon Goldensohn?

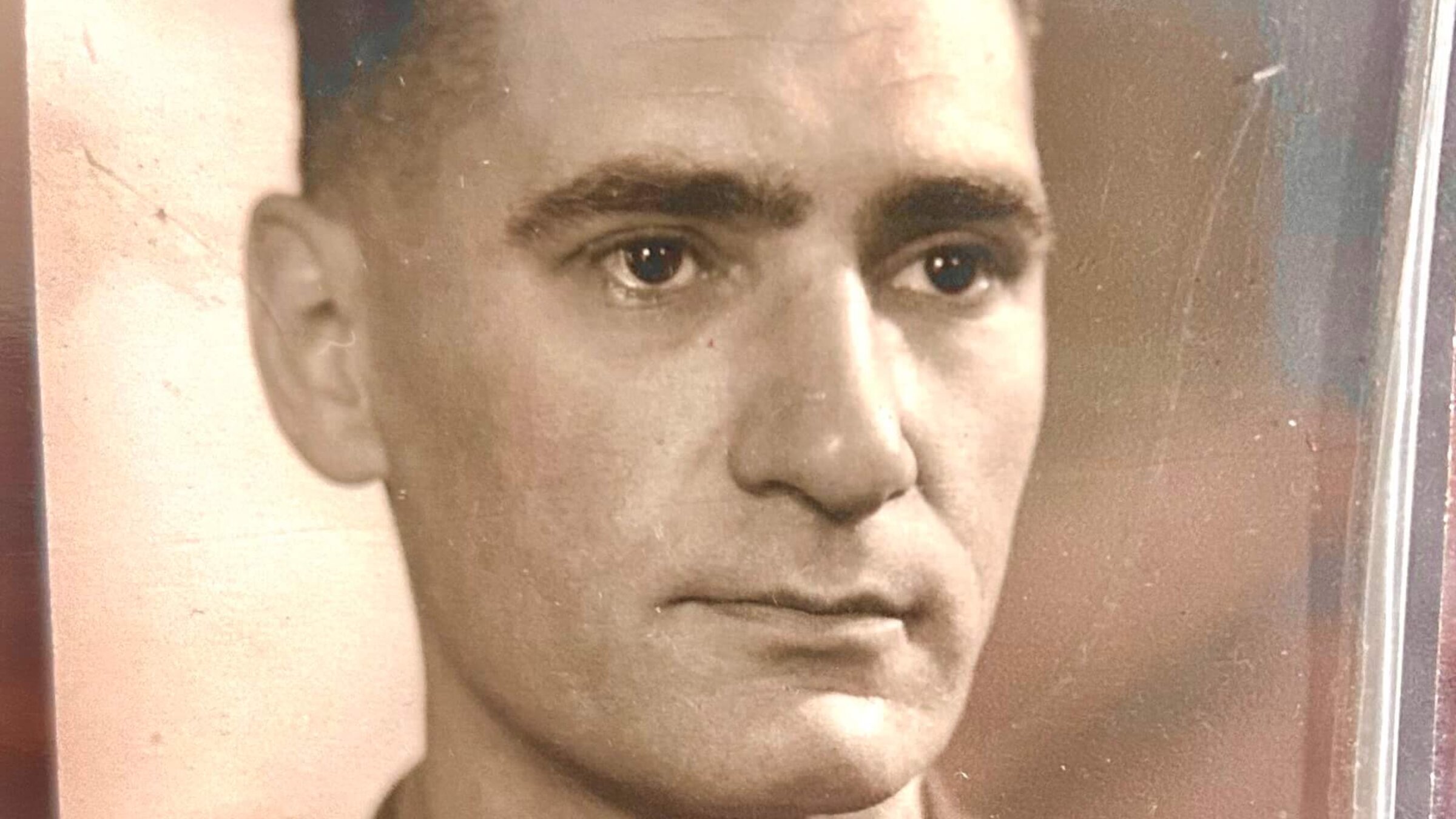

Leon Goldensohn replaced Kelley at the historic war crimes trials. Courtesy of the Goldensohn Family

Douglas Kelley, the real-life U.S. Army psychiatrist portrayed by Rami Malek in the recently released motion picture Nuremberg, wrote a book titled 22 Cells in Nuremberg that came out in 1947, a year after he finished his five-month stint at the Nuremberg trials.

Nearly 60 years later, interviews conducted by Leon Goldensohn, a Jewish psychiatrist who replaced Kelley at the historic war crimes trials, were published in The Nuremberg Interviews: An American Psychiatrist’s Conversations with the Defendants and Witnesses. Goldensohn spent more time with Nazi prisoners than Kelley did, and this book, translated into 16 languages, arguably sheds more light on the Third Reich criminals.

Goldensohn and Kelley were responsible for monitoring both the physical and mental health of the Nazi prisoners, and both their lives ended tragically: Goldensohn died of a heart attack in 1961, five days after his 50th birthday; Kelley died by suicide in front of his family at the age of 45.

Leon Goldensohn’s son Dan, now 77, said that his father’s interactions with the prisoners were deeper than the ones Kelley had.

“There’s a couple of defendants who say in Leon’s book how much they preferred talking to him,” Dan Goldensohn told me.

One of those defendants was Hermann Goering, the commander of the Luftwaffe, the German air force, who complimented Goldensohn on his technique as a psychiatrist.

“I feel freer to talk to you than to some other psychologists,” Goering told him.

I checked in with Leon Goldensohn’s sons and daughter and their cousins when the movie Nuremberg opened and the actor portraying Douglas Kelley appeared larger than life on the silver screen. The movie was about “the wrong psychiatrist,” Dan Goldensohn told me over the phone.

“We lost our chance to have Leon’s work once again in the public eye, because of Kelley,” Dan said. “When people talk about an Army psychiatrist at Nuremberg, Kelley’s name comes up. Leon’s name hardly does. Anyway, we have our jealousies.”

A French production company did make an hour-long program based on the Goldensohn book that aired on The History Channel, but the psychiatrist’s surviving relatives said it was not well done. Dan Goldensohn said the family came close to signing a deal with an Italian company for a film or TV series based on the book.

“It suddenly collapsed as soon as they heard that this other movie was signed with real actors and a real director,” he said.

‘The best brother in the world’

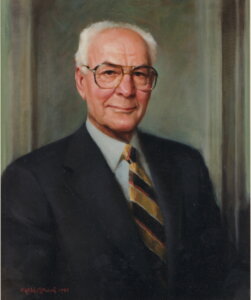

Dr. Eli Goldensohn, a world-renowned neurologist at Columbia University who died in 2013 at 98, took up the book project when he retired at the age of 83. Eli, who was four years younger than Leon, spent 10 years gathering and organizing materials, writing short summaries of all the interviews, and transcribing all those that hadn’t been transcribed. Eventually, he donated his brother’s papers to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

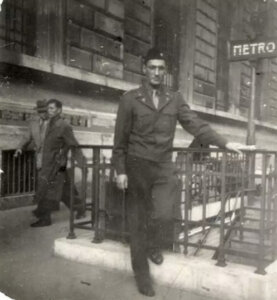

When the book was published in the fall of 2004, Eli Goldensohn told me his only disappointment was that it “didn’t really describe Leon’s wonderful war record.” Leon Goldensohn had been Division Psychiatrist of the 63rd Infantry Division, which fought in France and Germany, and received several decorations for service on the front lines.

Eli remembered his older brother fondly.

“The Nazi prisoners respected Leon because he was an objective person and was fundamentally a gentleman who was able to meet them on any level,” Eli told me back in 2004. “He was the best brother in the world. I did this book to memorialize the existence of one of the finest people I ever knew.”

Anticipating Hannah Arendt

Eli Goldensohn’s son and daughter assisted him on the book. Ellen Goldensohn, who had served as editor-in-chief of Natural History magazine for many years, helped with the copyediting. Her brother Marty Goldensohn, a veteran of public radio newsrooms, introduced Eli to his friend Jim Bouton, the former Yankee pitcher and best-selling author, who convinced Eli to pursue a deal with a major commercial publisher. (Eli ended up signing with Knopf, where the interviews were turned into a book by Ashbel Green, the editor who had worked with such dissident writers as Andrei Sakharov, Jacobo Timerman and Vaclav Havel.)

Ellen Goldensohn said her uncle Leon’s work was prescient, given that it came 17 years before Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.

“In 1946 he really knew the banality of evil and what was asked of these people who ran the Nazi regime,” she told me.

Marty Goldensohn remembers that his mother Betty, who lived to be 101, complained about her husband commandeering the extra bedroom in their assisted living apartment for the book project.

“Eli, get these file boxes out of here or I’m going over to the other side,” she joked, the other side being the Third Reich.

Marty said his father’s labor of love on the book was motivated, in part, by a sense of history, something he shared with his brother Leon.

“Leon was a Jewish doctor and he had compassion,” Marty told me. “He was in the middle of something that the historian Tony Judt once described as ‘a seam of evil.’ He was at the seam and how could he resist asking the key questions that had to do with the horror that had been perpetrated?”

The ‘Good’ German

Of the 476 pages in The Nuremberg Interviews, 33 are devoted to Goering, who told Goldensohn he was nauseated by Picasso, referred to the virulently antisemitic newspaper Der Sturmer as “that stupid journal” and claimed that of all the accusations leveled against him, the charge of looting art treasures caused him the most anguish.

In conversations with Goldensohn, Goering insisted that he was never antisemitic, that Adolph Hitler was a great leader who was betrayed by some of his subordinates and that he, Goering, would go down in history as a man who did much for the German people.

When Leon Goldensohn pressed Goering on his culpability in the genocide of European Jewry, the prisoner gave a classic “Good German” defense: “Certainly, as second man in the state under Hitler, I heard rumors about mass killings of Jews, but I could do nothing about it and I knew that it was useless to investigate these rumors and to find out about them accurately, which would not have been too hard, but I was busy with other things,” he said. “And if I had found out what was going on regarding the mass murders, it would simply have made me feel bad and I could do very little to prevent it anyway.”