Hey, Irving — why are there so many Jews named Irving?

A mystery of Jewish nomenclature finally solved — in honor of all the Miltons, Seymours, Sidneys and Irvings out there

From left, author Irving Wallace, composer Irving Berlin, and actor Henry Irving. Photo by Getty Images

My mother wasn’t a big one for jokes, but there was one she liked to tell. Years later, it showed up in the book Old Jews Telling Jokes, from which I quote:

A lady is taking her young son to his first day in school. She’s walking him to school and she starts giving him a little lecture.

She says, “Now, bubele, this is a marvelous thing for you, bubele. Bubele, you’re never gonna forget it. Just remember, bubele, to behave in school. Remember, bubele, anytime you want to speak, you raise your hand.”

They get to the school and she says, “Bubele, have a good day. I’ll be waiting for you when you get out of school.”

Four hours later, she’s standing there, and the little kid runs down the steps. She runs toward him and says, “Bubele, bubele, it’s been such an exciting day. Tell me, bubele, what did you learn today?”

He says, “I learned my name was Irving.”

I, on the other hand, am a big one for wordplay. Years ago, I reviewed Margaret Drabble’s novel The Ice Age, which begins with an epigraph from a William Wordsworth poem, “London 1802”: “Milton, thou shouldst be living at this hour.” I opened the review by quoting the line and saying it was “not, as you might expect, the plaint of a Miami Beach widow.”

The humor in both cases, such as it was, rested on “Irving” and “Milton” being stereotypical American Jewish names. The stereotype is accurate. It is easy to think of examples (Irving Berlin, Irving “Swifty” Lazar; Milton Berle, Milton Friedman), and there’s also data to back it up. In a 2016 MIT study, researchers ingeniously culled data from Jewish U.S. soldiers in World War II (median birth date: 1917) and found that Irving was the single most common given name; Milton was 13th. Those scholars, and others, have briefly commented on the popularity of those two names and some others that made the top 30 list for Jewish G.I.s: Sidney, Morris, Stanley, Murray and Seymour.

But the comments have missed an important point about the phenomenon, which I call “My name is Irving” (MNII). It even slipped by the late Harvard sociologist Stanley (emphasis added) Lieberson, who wrote frequently and perceptively about the factors that go into parents’ naming decisions. In his 2000 book A Matter of Taste: How Names, Fashions, and Culture Change, Lieberson mentioned his own first name, plus Irving and Seymour, and described them as attractive to Jewish parents because they were “names that [were] … popular with fellow Americans.”

That isn’t really true. As the MIT study says, MNII names “stand out as favored by the Jewish immigrants but not by the general population.” According to Social Security Records, Irving was the 106th most popular name for all boys born in 1917, Milton the 75th; Stanley did a bit better at number 34. The others listed above are similarly low in the general count, especially Murray (241) and Seymour (242).

Someone else who has written widely in the field, Warren Blatt, called “Irving, Morris, Sidney, Sheldon, etc. … Anglo-Saxon names that were popular 100 years ago.”

That moves the discussion in the right direction but is misleading, because the word “popular” implies that they were traditional first names. In fact, Irving, Milton, Sidney, Morris, Stanley, Murray, and Seymour are venerable upper-crust British surnames. Only two of them are even mentioned in The Oxford Dictionary of English Christian Names (1947), Sidney and Stanley; the book notes that the latter’s “use as a Christian name is apparently a recent development, originally due to the popularity of the explorer Henry Stanley (1841-1904).”

I hasten to say that Blatt was correct about other names in the G.I. top 30, such as William, Robert, Harry, Bernard, George, Harold and Arthur. And his point does hold for girls. I think of my mother (Harriet) and my aunts Fay, Florence, Sylvia, and Estelle; we didn’t have a Sophie in our family, but many others did. All born roughly between 1905 and 1920, all given posh British names.

The last-name-to-first-name trend — which I’m not aware of having previously been discussed — hit quickly. Among the ten most common boys’ names for native-born members of Yiddish-speaking American households (that is, kids) in the 1910 census, there’s only one of the MNII type (Morris, at number 7). The others, in order, are Samuel, Louis, Harry, Jacob, Abraham, Isadore, Max, Benjamin and Joseph.

What caused MNII to hit so soon after that? It’s impossible to say for sure, but it was not trivial. As Lieberson and a co-author once observed, looking at first name choices offers “a rare opportunity to study tastes in an exceptionally rigorous way.” I imagine the trend originated with some culture-loving Jews, who had been in the new country for a decade or more, who may have read Paradise Lost or seen Sir Henry Irving or one of his many thespian relatives on the stage, and thought such a distinguished name would cast a shimmering reflection on their sons. (And remember that they had a hall pass to use freely in their choices because of the custom of giving kids a Hebrew or Yiddish name as well.) Peers agreed, and soon the trend went viral.

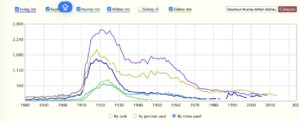

MNII dissipated as quickly as it hit, in some ways a victim of its own success. That is, it’s not necessarily attractive to give your kid a stereotypical name. There aren’t handy charts for later Jewish names along the lines of the World War II survey, but Social Security data for the whole country shows the MNII names peaking in popularity in the late teens and early ’20s, then cratering.

In the 1930s and ’40s, there were a lot of Normans, Henrys, Daniels, Jerrys, Howards and Philips; and the popular ’50s Jewish boys’ listed by Warren Blatt names rings true for my mischpocheh: Alan, Andrew, Barry, Bruce, Eric, Harvey, Jay, Marc, Michael, Peter, Richard, Robert, Roger, Scott, Steven and Stuart. After that it was, and has been, back to the future, what with the flood of Noahs, Joshes, Sams, Bens, Isaacs, Abes, Maxes and Jakes.

While Irving is a lost cause (it fell out of the top 1000 boys’ names in 2005, according to Social Security), MNII has a legacy: it arguably popularized the practice of giving last names as first names, which, judging from the current generation of young adults, is stronger than ever. Just ask Taylor Swift, Madison Cunningham, and consensus NBA Rookie of the Year Cooper Flagg.