Why small town Jews buried their dead in big cities — and what those journeys reveal today

Funeral trains linked isolated Jews to larger communities, revealing how belonging could stretch across counties, rail lines, and faiths

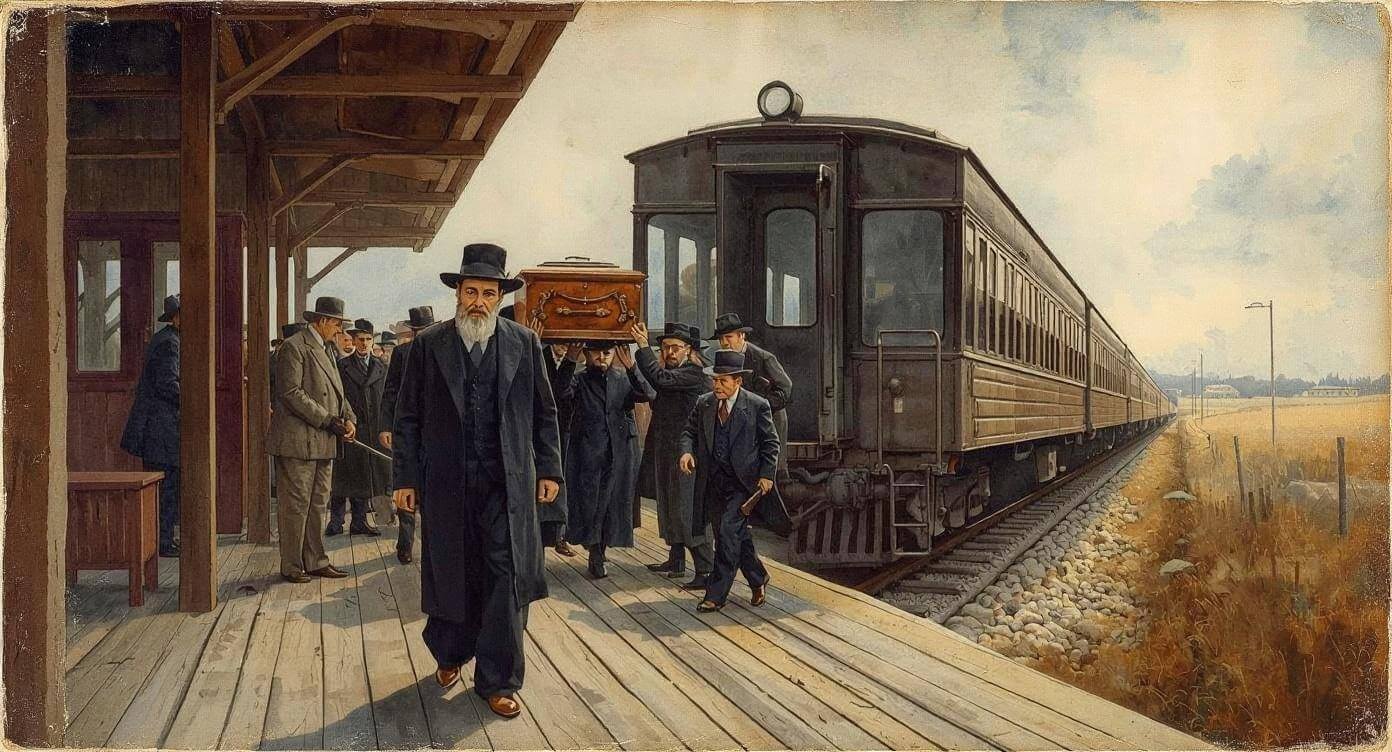

An AI-generated image of mourners loading a coffin onto a train. Graphic by Canva AI

The train that carried John Friday’s body from Athens, Ohio, in October 1886, was headed three hours west to Cincinnati for burial at the Walnut Hills Jewish Cemetery.

Yet even as the burial took place far from home, the town he left behind stopped to mourn him. Many businesses closed. The mayor convened an assembly in his honor. Local papers said that no citizen’s death “would have created a greater vacuum in our community.”

In a county with no synagogue and only a handful of Jewish families, the rituals of Jewish burial unfolded across distance — but the grief was local, immediate, and deeply felt. The train carried Friday away. But Athens kept vigil.

His funeral showed something that was once common in small towns across the United States but often forgotten today: for generations, American Jewish life has taken root far from major urban centers. Rich stories from American Jewish history can be found even in areas and decades in which no organized Jewish communities were present.

For countless Jewish families in small towns, where there were often no local Jewish cemeteries, the journey to burial became its own ritual — a moment when the town gathered, honored, and then released one of its own for burial among the Jewish people.

Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, arguably the most influential American rabbi of his era, presided over Friday’s burial in Cincinnati. Meanwhile, in Athens, Mayor Judiah Higgins signed a public resolution praising Friday’s “enterprise,” his kindness as “a man dear to all,” and “deep devotion to the interests of his adopted town.” Two places mourning the same man. Two communities claiming him in different ways.

This was not unusual. It was part of a larger pattern. Across the Midwest, the same story repeated itself.

In Chillicothe, Ohio, Moses Bottigheimer died in 1897 after 25 years in business. The local paper noted that Jewish residents were buried in Cincinnati or Columbus because Ross County had no Jewish cemetery; yet even before then, several families had already chosen to honor their loved ones at the town’s own Grandview Cemetery — a reminder that Jewish burial in rural America was never a single story but a series of adaptations, gestures of care and remembrance shaped by circumstances.

Almost 20 years later, in Anderson, Indiana, Louis Loeb passed away after living in the town for more than half a century. He was a fixture of the community, known for quiet acts of charity and for “his loyalty to friends, and always a close adherent to a principle he believed to be right.”

When he died in 1915, a Presbyterian pastor and Reverend George Winfrey of the First Christian Church in Alexandria, a nearby town, conducted the funeral in the family home — a common practice in communities without a local rabbi. After the service, his remains were taken to Cincinnati for burial in the United Jewish Cemetery. The local paper wrote that “Anderson will miss Louis Loeb,” calling him a man whose life had strengthened the town and declaring that his memory would “live for years with those who knew best the many strong and vigorous qualities of the man whose only ambition was to live a quiet and unostentatious life.”

Again and again, in places too small to sustain synagogues or cemeteries, distance did not lessen devotion. Towns gathered around the departed; Jewish families sent their loved ones to cities where a Jewish burial could be completed; and in the space between those two acts, a sacred form of mourning emerged — one marked by the belief that dignity can be shared across many miles.

For a great number of Jewish families in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the nearest Jewish cemetery was not local, but hours away — often in larger regional cities like Cincinnati. Burial was one of the few moments, alongside weddings and the High Holidays, when isolated Jewish families reconnected with the broader Jewish community.

From rural areas, bodies traveled by wagon, then by train, then by carriage again for the final mile. If you trace the burial registers of cemeteries like Cincinnati’s Walnut Hills, you will find names from dozens of small towns: Athens, Xenia, Chillicothe, Piqua, Portsmouth, Jackson. In many of these places, no synagogue ever stood, no cemetery wall marked a Jewish space — yet here too Jews lived, worked, raised children, and loved their neighbors.

This is something we forget when we search only in cities for Jewish history. The absence of headstones in a small town does not mean the absence of Jews. It means their final resting place lies elsewhere, but their stories still belong to the towns where they lived their lives.

And so the last journey became a ritual in itself. Families accompanied the body to the station; friends and neighbors filled the home sharing condolences; merchants closed their businesses as a sign of respect. More than once, a town gathered to watch the funeral train pull away — a moment as solemn as any burial service.

The cemetery was distant. But the mourning was local.

A civic shiva

In ways that are easy to overlook now, these departures tell us something profound about Jewish belonging in rural America: that community existed even where institutions did not; that reverence could be local even when ritual was not; and that the townspeople who lined the streets were participating in a kind of civic shiva — one made of presence, respect, and the understanding that a life can shape a place long after the body has left it.

It is heartbreaking to imagine how many such stories have faded from local memory simply because the grave is elsewhere. If John Friday’s descendants looked only in Cincinnati, they might have known him as a respected businessman who chose to be buried as a Jew — but they would have missed the part where an entire town closed its doors to grieve him.

The paper said his death left “a vacuum in our community.” A loss like that is not created by a stranger. It is created by a neighbor.

When we lose the local context of a life, we lose more than a footnote. We lose the texture of belonging — the conversations in a shop, the familiar nods on the street, the civic friendships, the quiet ways towns knit themselves together.

Jewish cemeteries in cities hold the remains of thousands who never lived there. Their names are inscribed in stone, but the stories that shaped them are scattered across counties and crossroads now often forgotten.

To remember them rightly, we have to look both ways: toward the city where they were buried, and toward the small town that mourned when the train pulled away. This is a more complete act of zachor, remembrance.

The distance between those places — the miles of track, the rituals divided across geography — is not emptiness. It is the space where American Jewish life once unfolded: improvised, interwoven, sustained by neighbors who understood that belonging does not require shared faith, only shared humanity.

And if the grave lies in Cincinnati, the grief still belonged to Athens. The memory does, too.

These journeys reveal something enduring: that holiness is not confined to where we are buried but to where we are loved.